Ethiopia plans ambitious resettlement of people buffeted by East Africa drought

Loading...

| Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

In Ethiopia's rain-starved eastern badlands, livestock is the sole asset for most. Swaddled in robes, pastoralist families traverse huge tracts searching for water and pasture for their herds, uprooting camps as they go. When seasonal rains fail, life becomes a battle for survival.

As aid agencies scramble to feed some 11.5 million people suffering from what is being called the Horn of Africa's worst drought in 60 years, Ethiopia's government is enacting a resettlement program that it hopes will be a longlasting solution to a longstanding burden.

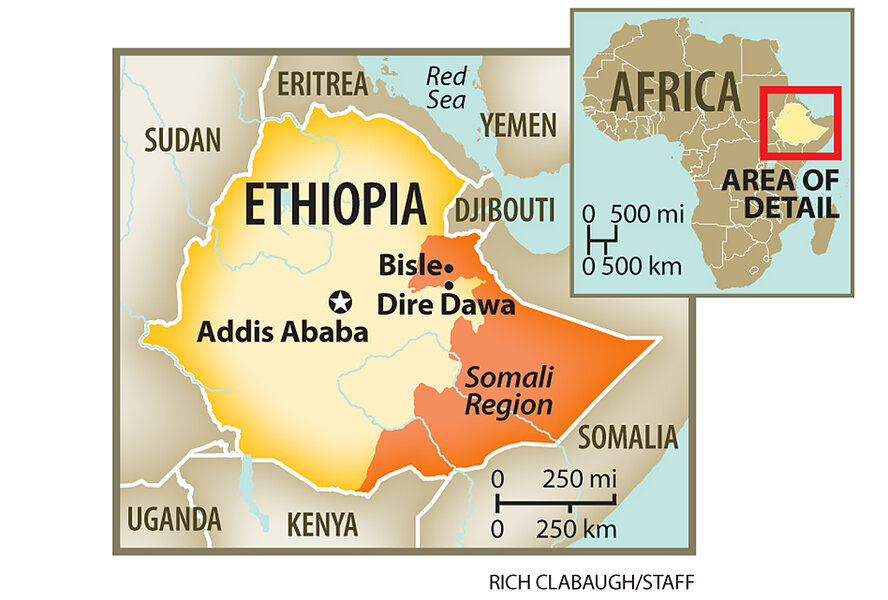

In its far-flung regions, including the vast east, populated mostly by ethnic Somali pastoralists, Ethiopia wants to group its scattered semi-nomadic peoples into permanent settlements, largely ending a mobile lifestyle that has sustained people for centuries.

In many ways the plan sounds all too familiar. During the catastrophic famine in the mid-1980s, Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam's Marxist junta forced highlanders across the country to fertile lowlands. Tens of thousands perished en route or died in their new, alien surroundings. This time, however, the government says resettlement is voluntary and consists of regional destinations instead of a mass, cross-country exodus.

In the Somali region, which has just under 1.5 million people out of about 5 million in need of food aid, the idea is to create villages near rivers and build irrigation systems, roads, health clinics, and schools. The government sees this as a life-saving measure and as a way to help the pastoralists benefit from Ethiopia's double-digit economic growth. A government pastoralist project with the long-term aim of resettlement will receive some of the $500 million for "building long-term drought resilience" in the region, the World Bank said in late July.

"Especially for pastoralists, the solution is development interventions," says Agriculture State Minister Mitiku Kassa, "water-centered development. Most areas have surface water and there are rivers." In the dry regions of Somali and Afar, the government hopes 500,000 people in each will resettle, while in the western states of Gambella and Benishangul-Gumuz it wants 450,000 to move.

The pastoralist lifestyle is becoming difficult to sustain, says Eugene Owusu, the United Nations humanitarian coordinator in Ethiopia. "Therefore they need to look at alternative development solutions." Although initially donors were slow to support the program, he has "no doubt" it could have a transformative effect on struggling communities "if it's done well."

But some activists say the programs overseen by local governments will be coercive and rob people of their ancestral lands. They cite an incident in Gambella in which a family that was reluctant to move had their huts torched, possibly by local officials. Others say giving Ethiopia's estimated 9 million pastoralists services without impeding their traditional lifestyles is a better way.

A few miles north of Dire Dawa, Ethiopia's second-largest city, barely a leaf is visible. In some patches, bushes have disappeared, leaving only sand and fearsome heat that can top 104 degrees F. The herders who live there can deal with occasional dry spells, but the frequency has pushed coping mechanisms to breaking points, aid workers say.

"When they are hit with several dry seasons in a row, the result is a crisis," says David Wightwick of Save the Children (STC) UK. He is working in Bisle village, 34 miles north of Dire Dawa. "And at the moment it's going from crisis to catastrophe."

Humanitarian facilities here are crowded with mothers and children who have walked hours in search of help, among them, Lula Robe and her malnourished baby. "Five years ago we had 100 sheep and goats, but now we have 10," Ms. Robe says, clutching a bottle of donated cooking oil. "We have lost our livestock to the drought." Her family of 10 is now reliant on handouts.

These stories are common across the region, which has endured three similar crises since 2000. The problems in Bisle are the "tip of the iceberg," says STC's Katy Webley.

Pastoralists, who dominate a profitable livestock trade, are used to weathering harsh conditions, says Holly Welcome Radice, an STC Ethiopia livelihoods expert, and their customs should be supported instead of transformed, "Historically pastoralists are very adaptable and resilient because they live in harsh places," she says. "They are there because nothing else can be done there."

While pastoralists should have access to public services, cellphones, and the Internet, a mass change is unwise because, she says, "these are environments that are not able to sustain huge sedentary populations."

Ms. Radice says the solution lies in working with historically marginalized communities to take measures such as restoring pasture and increasing vital mobility hindered by private landholdings, borders, or conflicts. "You have to understand what is really causing the crisis – it's not just the failure of rains. It has to do with people's failure to access services; it's people's failure to have a political voice."

But Ethiopia is not known for buckling to foreign charities and it's almost certain that views like Radice's will not shape the pastoralists' future.

"For the long term, the government wants to support pastoralists to pursue sedentary lives along the banks of primary rivers," says Assefa Tewodros, coordinator of the state's Pastoral Community Development Project. The pressures of land degradation, conflict, climate change, and population spikes, he says, mean this is the only option, as the hinterlands are too vast for the government to provide services to dispersed herders.