Robert Mugabe clamps down further in Zimbabwe

Loading...

| Harare, Zimbabwe

In a normal country, preparations for an election look a bit like this: dozens of eager young activists put up posters, candidates meet with community leaders to seek their support, and middle-aged party members walk door-to-door to meet the voters.

In Zimbabwe, election season means violence.

For months, President Robert Mugabe’s supporters in the military and the police have terrorized villagers in rural areas where many in 2008 supported opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai and propelled him into the seat of prime minister.

And in the past few weeks, the violence has spread to urban areas with the seeming intent of intimidating those who would vote for Prime Minister Tsvangirai and his Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party.

While such tactics long preceded the recent coup in Tunisia that instigated massive antigovernment demonstrations this week in Egypt, analysts say Zimbabwe's strongman president is taking note of North African events as he strengthens his grip. Indeed, President Mugabe, says political analyst Takura Zhangazha, may speed up plans for parliamentary elections to capitalize on a current wave of violence and voter intimidation – conditions he sees as favoring his party.

Mugabe loyalists seen behind unrest

MDC members say the offensive, which started last week in Tsvangirai’s political strongholds of Harare and Chitungwiza, involves the police and the military, war veterans of the liberation struggle, and youth militia from Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party. All the assailants are known for their unwavering loyalty to Mugabe.

Chitungwiza, a dormitory town of more 2 million people, is 25 kilometers southeast of Harare.

ZANU-PF spokesperson Rugare Gumbo denies that his party is spearheading political violence or that it is working with security forces to decimate the MDC. “We have heard that before every time there is talk of election,” he says. “They are afraid of losing an election.”

The violence is just the latest sign that not all is well with the coalition government, put together in February 2009 after months of political stalemate. Mugabe’s cabinet meetings are reportedly more and more fractious. Meanwhile, MDC members are decrying breaches in the coalition’s powersharing agreement, which divided control of several ministries but left Mugabe in charge of the military and security agencies.

The political squabbling is nothing compared with the violence faced by those on the front lines in villages and towns.

Violence spreads to cities

The spread of violence to cities is a recent phenomenon, and a dangerous turn for Zimbabwe politics. In previous election years, political violence was mainly concentrated in those rural areas where ZANU-PF still commands some support.

In the past week, scores of MDC supporters were injured in Harare’s high-density slums after they clashed with ZANU-PF supporters, who are in most cases backed by armed uniformed soldiers, police, and war veterans.

Presently, at least two MDC supporters are in an intensive care unit at a private clinic. One of them was shot by unidentified soldiers in Budiriro, a suburb of the capital that is touted as Zimbabwe’s own “Baghdad” and is a popular support base for Tsvangirai.

An MDC activist, who identified himself only as Amon for fear of victimization, says he saw his colleague being gunned down by a group of soldiers in Budiriro.

“I saw one of them pointing a gun and I thought he wanted to shoot me so I started running,” he says. “I heard William’s loud cry and I knew he had been shot but I continued running, fearing that they will fire another one.”

In a scene reminiscent of the violent June 2008 elections, 150 MDC supporters huddled together at the party’s headquarters in Harare’s Central Business District (CBD) this week after they were chased out of their homes by ZANU-PF youth militia, soldiers, and war veterans.

'You could have another bloodbath'

Police spokesperson Wayne Bvudzijena denies that the police are Mugabe partisans, saying instead that it is the MDC that has provoked ZANU-PF supporters. “In most cases, MDC activists are the ones who provoke and rush then to the police to report,” he says. “The police are never partisan. We are a professional force.”

The surge in politically motivated violence comes barely a week after the MDC secretary-general, Finance Minister Tendai Biti, warned that Zimbabwe could face a “bloodbath” at elections this year if the international community does not help to prevent the crisis.

“The tell-tale signs are already there that you could have another bloodbath,” said Mr. Biti.

MDC spokesperson Nelson Chamisa says ZANU-PF is trying to provoke his party so that the violence degenerates into anarchy.

“Whenever there is an election, ZANU-PF starts a campaign of violence against the country’s innocent citizens,” says Mr. Chamisa, who also heads the Ministry of Information Technology Communication in the coalition government. “It is not a civil way of transacting politics in this day and age.”

Why violence started now

The current wave of violence started when ZANU-PF mobilized and bused in youths from rural areas to demonstrate against the slashing of maize crop by Harare City council recently.

Incidents of political violence have continued to rock the country since last month when Mugabe, who has ruled the country with an iron fist for the past three decades, announced his determination to hold elections this year.

Political analyst Takura Zhangazha says that by unleashing soldiers and militia, ZANU-PF was trying to measure its ability to destabilize the MDC ahead of both the referendum and elections.

“Urban areas have been areas of concern to ZANU-PF,” says Mr. Zhangazha. “They are trying to measure their ability to destabilize the MDC well ahead of elections by targeting its leaders and activists.”

Mugabe's tactics

Other analysts said Mugabe has, since 1980, when Zimbabwe gained independence from Britain, used violence against adversaries to maintain power. In the March 2008 elections, Mugabe used violence against MDC supporters, hoping to force Tsvangirai to back out of the vote. At least 200 MDC activists were killed by suspected ZANU-PF supporters and state security agents.

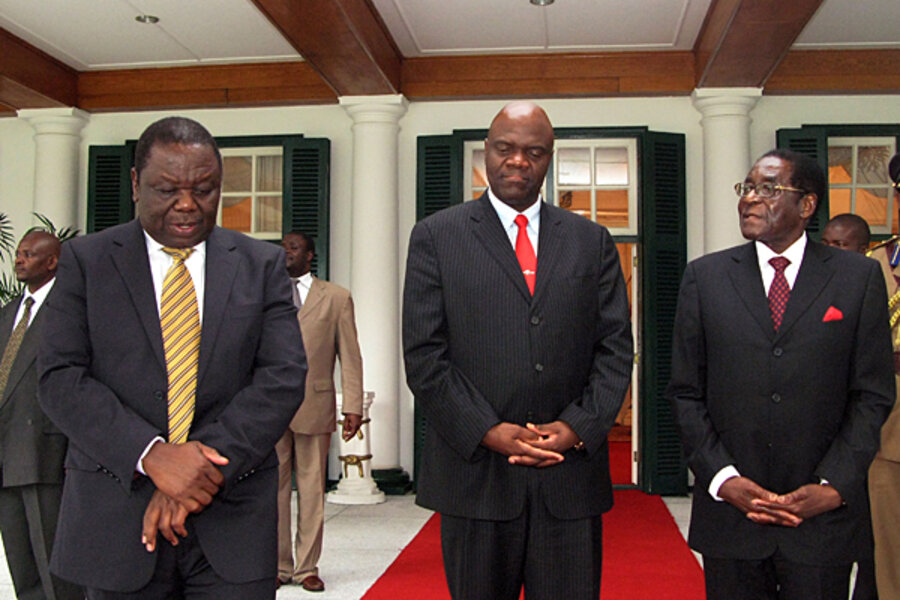

Zimbabwe’s unity government, which comprises Mugabe’s ZANU-PF, Tsvangirai’s MDC, and a rival MDC faction headed by Arthur Mutambara, is facing total collapse because of deep disagreements within the coalition over political reform.

Under the Global Political Agreement (GPA) signed in September 2008 and implemented in February 2009, the three principals are supposed to hold consultations leading to a new constitution, which would then have to be approved by a referendum before new elections can take place.

But Mugabe this week threatened to dissolve parliament and call early elections, without waiting for a new draft constitution.

“I have the constitutional right to call an election on the basis of the old Constitution,” Mugabe said on Monday. “If the constitutional process is not wanted, I will have parliament dissolved and call elections.”

Such a hard line by Mugabe flies in the face of South African President Jacob Zuma, a facilitator in the Zimbabwe post-election crisis, who has been pressing the three principals to come up with and implement a roadmap ahead of elections.

African neighbors called to help

MDC spokesperson Chamisa says Mugabe wanted to ambush the MDC into a snap election.

“ZANU-PF has not abandoned guerrilla tactics,” he says. “We suspect he wants an election before our own congress. He [Mugabe] thinks he will catch us flat-footed. No, for us, if one eye closes, the other one is wide open.”

The MDC has expressed concern for the lack of action by the police as “innocent citizens” are harassed for belonging to a political party of their choice. Police are victimizing MDC activists even when they are victims of violence, MDC members say, while they protect ZANU-PF militia from prosecution.

“It is clear that the repeat of June 2008 in an amplified version is inevitable,” Chamisa said in a statement. He has called on the African Union and the Southern African Development Community, who are the guarantors of the Zimbabwe agreement, to take immediate action.

The Monitor's correspondent in Harare cannot be named for security reasons.