South Africa AIDS orphans overwhelm social work services

Loading...

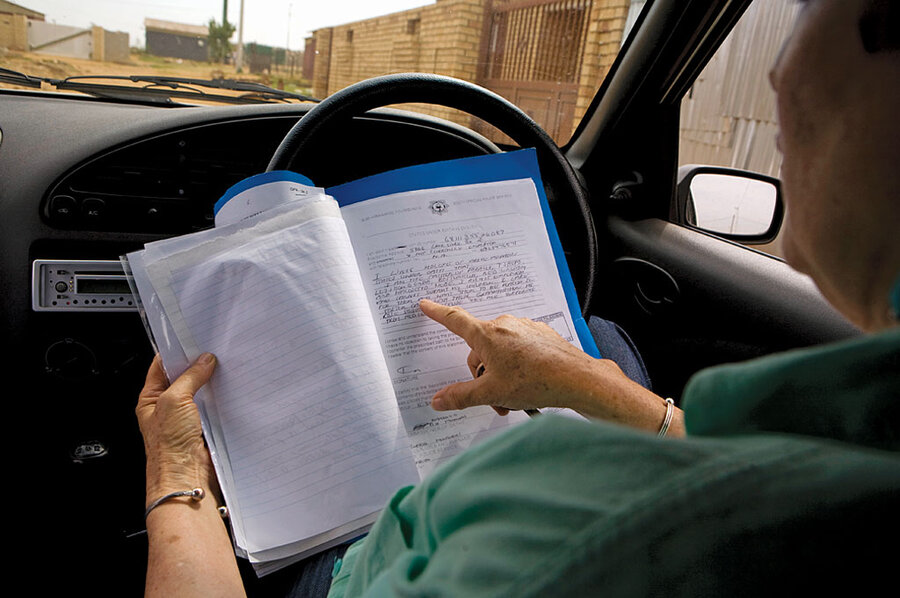

| Soweto, South Africa

Lora Doman sees more human drama, suffering, and courage in a single morning than most South Africans ever see.

Ms. Doman is not a nun, or a saint. She is one of South Africa’s 12,000 social workers, a front-line soldier in a battle to hold her country together, one family at a time, several families a day, ensuring that abused, neglected, or orphaned children have a home.

It’s a monstrous task in a country where an estimated 5.5 million people – roughly 18 percent of the population – are believed to be infected with the HIV virus.The AIDS epidemic not only kills millions of South Africans, it also orphans children. A United Nations and World Health Organization report last year estimated that as of 2007 there were 1.4 million South African AIDS orphans – a tripling of the number estimated in 2001, and the largest concentration in the world. For homes, many of these AIDS orphans must turn to their extended families – many of whom are already living in poverty – and to overwhelmed orphanages and shelters for survival.

Doman, a relentlessly positive woman who works for the Roodepoort Child Welfare Agency, meets this enormous task each day with a mixture of urgency and hope. She regularly works 10 hours a day, attending to family tragedies from the rough streets of Soweto to the middle-class neighborhoods of Roodepoort. She typically carries a caseload of 450 clients.

Doman says she realizes that even if she met with one family each workday in a year, and did nothing else, she could never keep up. As more cases arrive, she may never even meet all the people she’s responsible for.

“It’s ludicrous to think that one social worker can do all this,” says Doman, matter-of-factly, pulling into the driveway of a client on a dusty street of the informal settlement of Braamfishcerville.

“If you have a crisis,” where a child has to be removed from an abusive or neglectful home, “then you become so busy – constantly in court, doing investigations, writing reports, finding a place of safety for the child – that all the other cases that you have to handle get pushed off for later.” She turns off the engine of the car and smiles wryly, “[W]e are just putting out fires.”

• • •

The AIDS crisis in Africa has claimed 25 million lives since 1981 – equal to half the death toll of World War II. Since most of those who have died are of childbearing or child-rearing age, from 15 to 49, the impact falls hardest on the children left behind and the communities that have lost not just parents, but laborers, nurses, teachers, and others who keep African societies and economies functioning. It’s a silent demographic shift that is weakening Africa precisely at the time when the growing global demand for resources should be making the continent prosperous and less reliant on aid. At the current rate, AIDS could create as many as 35 million orphans on the continent by the end of this year, according to UNICEF. (In South Africa, only about 11 percent of children orphaned by AIDS are HIV positive.)

The fact that it is international agencies – and not the South African government – that make estimates of HIV infections and of AIDS orphans is significant. While South Africa’s current president, Jacob Zuma, has taken the country’s HIV crisis seriously, his predecessor, Thabo Mbeki, was a self-described AIDS denialist. He argued that there was no scientific link between sexual behavior and the spread of HIV, and that traditional herbal remedies were a better alternative to the latest antiretroviral treatments. His two terms in office, say AIDS activists, set South Africa back a decade in its AIDS-prevention fight.

While South Africa has Africa’s greatest concentration of HIV patients and AIDS orphans, it also has the best private and governmental social services to meet the challenge. But even so, experts say, South Africa’s social workers are swamped.

“Currently, we have 12,500 registered social workers, who care for all sectors – the elderly, the disabled, as well as for children – and the estimates are that we are only reaching a third of all the children in need,” says Lucy Jamieson, a senior advocacy coordinator at The Children’s Institute at the University of Cape Town. “We’re far short of the 16,000 child social workers that we need, and with the number of students we are currently graduating with social work degrees, we will not achieve the [necessary] number of social workers in the next 10 years. The solution has to be more radical.”

Many social scientists believe that countries like South Africa simply have to empower more professions – early childhood development counselors, social auxiliary workers, child and youth-care workers, community development workers – to get involved in the tasks that usually fall exclusively on the shoulders of social workers.

By killing a family’s breadwinner, AIDS puts millions of families into poverty, Ms. Jamieson says. But one possible remedy is for community development workers in poor townships to provide job training for grandmothers who become responsible for the orphaned grandchildren left behind, so they earn better incomes to support their enlarged families. Auxiliary child-care workers, normally given smaller administrative tasks, could be enabled to do home visits, Jamieson adds, and lighten the load on social workers.

This load is unquestionably heavy. “I have met social workers with over 2,000 cases, and 200 to 300 cases is quite common,” she says.

In theory, the South African government is already well on the way to solving its problems, with some radical new ideas embodied in its recently passed Children’s Act. But in reality, South Africa is standing still. Citing insufficient tax revenues, the South African government has yet to implement the Children’s Act.

The state lottery was used to augment salaries for social workers for a one-year period, and Doman’s $1,200-a-month pay went up to $2,000. But next year, salaries will go back down.

When an emergency case comes up, such as the abandonment of baby boy Umfile in a Roodepoort cemetery last year, Doman’s first call is to a foster mother like Eleanor Dustin. A white, middle-class South African, Ms. Dustin renovated her home to become a shelter, The Lighthouse, for abandoned children.

“It’s about the child,” says Mrs. Dustin, holding the now healthy Umfile in her living room, during a recent home visit by Doman. Besides Umfile, Dustin has more than a dozen abandoned babies – most of whose parents are unknown, but assumed to be HIV-positive.

Dustin has taken the unusual step of putting a hole in the brick wall surrounding her spacious house in the upscale North Riding neighborhood and installing a “Moses basket,” where parents can leave infants anonymously. An alarm goes off in Dustin’s house to alert her when a child has been dropped off in the basket.

As the name “Moses basket” suggests, Dustin is a religious woman, and her faith helps her to keep going. “I do get tired,” she says, but “it’s through His grace that we’re able to do it.”

With nearly 43 percent of all South Africans living below the poverty line – defined as less than 400 rand ($53) per month – it is perhaps not surprising that many of the AIDS orphans in Doman’s caseload become financial footballs to be kicked around by family members. South Africa gives “child care” grants of $30 a month per child to poor families. And there are “foster care” grants of $90 per child per month for children who have lost at least one parent. Nearly 9 million South African children receive child-support grants, and the case of Rose Sesotho indicates just what a source of tension they can be within impoverished families.

Mrs. Sesotho came to Roodepoort Child Welfare in 2007, when her daughter Mary Jane Mebe died of AIDS, leaving Sesotho with six grandchildren to care for. Two of these children have HIV and require constant medical treatment, one gets therapy for emotional stress, one has been diagnosed with arthritis, and another with epilepsy.

Sesotho – who takes heart medication herself – looks after these children the best she can, Doman says. But she’s been unable to get full custody because the children’s father – an unemployed Zimbabwean refugee – refuses to cooperate with the foster-care legal procedure. Having signed documents to transfer the children to Sesotho’s care, he now refuses to hand over birth certificates and other records. So Sesotho is unable to obtain government grants to help support her grandchildren.

“I buried my own daughter,” Sesotho says. “I have a small house. Four of us sleep in one bed. I have to borrow money at the end of the month.”

If the father would simply sign off on the foster-care agreement and give up any claims to the children, Sesotho would receive $540 a month in grant money.

“I need to fight for this family,” says Doman, after hearing Sesotho retell her story. “I need to prove that the children really need care, and that the father really will not do his part.”

• • •

As dark as Doman's cases can be, many also fill her with a sense of hope – like the case of 7-year-old Gift.

Celina Seloma – an elderly woman whose own sons have died – has looked after Gift for four years. Found neglected and ill in a tin shack in the northern Johannesburg township of Diepsloot, Gift was taken away by Roodepoort Child Welfare, and placed in foster care with Mrs. Seloma. Months after Gift came to stay, a doctor informed Seloma that the boy had HIV, probably contracted at birth from his mother.

Today, Gift is having medical treatment for HIV – the medicine provided free of charge under a US-funded program, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) – and he is healthy, sweetly mischievous, and the center of attention at Seloma’s home.

Other cases take Doman’s breath away, as struggling families set aside their bickering to act in the interest of the child.

Last year, Doman received a call to place the infant child of a teenage mother in foster care. The mother, 16-year-old Celina Mashiane, was perfectly healthy, but had reached her wits’ end living in the tidy brick home of her mother, Lucy Mashiane, and her stepfather.

Unlike many of Doman’s cases, AIDS was not a factor, nor was sheer poverty. Here, the problem was cultural tradition. Celina’s stepfather resented having an extra mouth to feed. Celina’s boyfriend refused to pay “damages” – an African tradition where, in lieu of marriage, young men who father children pay the mother’s family to help support the child.

The solution lay in finding a new way, Doman says, one that allowed Celina some space to finish school, and also relieved the financial burden required by African traditions.

Through painstaking negotiations with both Celina’s and the young father’s families, Doman encouraged shared custody. Today, the father’s family shares the financial responsibility for raising Celina’s baby, Amogelang.

Having a few days without Amogelang to look after allows Celina to go to high school, she says, and she has plans to attend college to become an accountant.

This solution “changed the way I thought about other things,” Celina says, holding her baby in the kitchen of her mother’s house. “I had to make decisions to do the right things for my future and the future of my child.”

Doman seems satisfied after a recent visit to Celina’s. As she settles into the drive to her next case, she says, “It keeps me going to see smart people take themselves to a new level.”

--

Related stories:

South Africa AIDS orphans: A foster mother can't cope

South Africa AIDS orphans: Gift's birth mother confronts his foster parents