On China's heels, India vies for its old edge in Africa

Loading...

| Lusaka, Zambia; and New Delhi

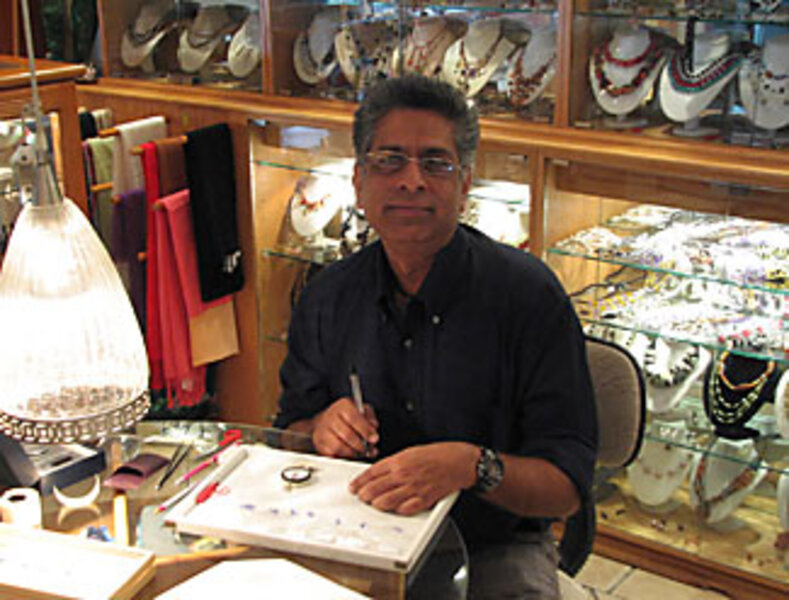

Raised near Hyderabad, India, Vasu Reddy never imagined he'd end up in Africa.

But 12 years after moving to Zambia as a mining engineer, Mr. Reddy now runs a small gemstone processing and sales operation with his wife, Aravinda. And over the last year or so, more and more visitors sipping coffee outside Reddy's shop, he says, are Indian.

Indeed, Indian firms are ramping up investment in Zambia, and across Africa. Indian mining giant Vedanta Resources PLC runs Zambia's biggest copper mine. Zambia's commerce minister pledged in March to set up a special incentive-laden investment zone to attract Indian companies.

Reddy's experience is the type that the Indian government is highlighting as it tries to draw a distinction with China, India's more Africa-entrenched neighbor – and its primary competition for natural resources on the continent.

"The first principle of India's involvement in Africa is unlike that of China. China says go out and exploit the natural resources; our strategy is to add value," says India's minister of state for Commerce, Jairam Ramesh, told representatives of 14 African nations at an April summit in Delhi designed to boost Indo-African ties.

But to date, India's investment lags in comparison to China's aggressive push into Africa to fuel its growing economy with oil, copper, and other resources.

India makes up for lost time

Indeed, after devoting little attention to Africa since the 1990s, India finds itself in an awkward position – making up for lost time on a continent where it has longstanding cultural and commercial ties. Whereas a decade ago, India topped China in Africa trade, China's two-way trade last year with Africa was $55 billion to India's $25 billion.

The Chinese, for instance, got their own investment zone in Zambia a year ago, when Chinese President Hu Jintao visited Zambia to great fanfare, announcing plans to build a new soccer stadium and pledging an eye-popping $800 million in copper mining investment.

"It must be a sore spot with India, because Indian-African relations go back … a century," says Venkatesh Seshamani, a Bombay-born economics professor at the University of Zambia who has lived in Zambia for 26 years. "But China has gone far ahead of them. [Indians have] missed the bus."

But the India-China comparison is not entirely fair, in part due to the two countries' economic models.

China's state-driven investment

"The Indian government and business sector came in ahead of the Chinese. This is almost like a second wave, if you like," notes Bradford Machila, Zambia's Minister of Lands. "The main difference between investment coming from India and the investment coming from China is that the Chinese entities ultimately are state-owned." With Indian companies, Machila notes, "there is no government that is underwriting what they're doing."

With the power of the central government and the full might of the Chinese economy behind it, no one can out-China China. "The Chinese have deep pockets. They have the ability to undercut and win every contract – and not just against India. It's the US and Europe, too," says Harry Broadman, a World Bank adviser on Africa in Washington.

But Mr. Broadman and others note that Indian companies are more diversified and say that India's tradition of private sector creativity may be its strength.

With last month's summit, the Indian government is beginning to act as a facilitator for Indian businesses to expand into Africa. During the past five years, India has extended credit worth $2 billion to African countries. At the summit, India promised to grant preferential market access for exports from all Least Developed Countries, 34 of which are in Africa. India will also increase its lines of credit to Africa to $5.4 billion and its aid to $500 million over the next five years.

The most problematic area of competition with China is for oil. India imports 70 percent of its oil, and is heavily dependent on Nigeria. In a move that has escaped much international scrutiny, the government-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corp. Videsh Limited has invested $720 million in Sudan to secure a share of oil fields, and plans to spend $200 million on a 741 kilometre (460-mile pipeline. India has offered $500 million in credit to countries around the Gulf of Guinea – the source of 70 percent of India's African oil production.

Political favors

In its courtship of Africa, India is also trying to build support for its effort to gain a permanent seat on the United National Security Council – something that Africa wants as well.

Some say the Indian government needs to be more proactive as a bridge between African governments and Indian businesses, pushing Indian businesses as solutions to development challenges throughout Africa. "The embassies should learn more about the ventures going on in their area," suggests Sachin Bajla, founder and CEO of Taurian Resources, a Mumbai-based mining operation. "Look at what are the needs of a foreign government and what Indian company can fulfill that need."

While China and other foreign mining companies generally export raw minerals from Africa, Zambia wants India to start manufacturing raw materials here. The Indian government is also financing an "e-network" project to enhance Internet connectivity in Africa.

In Zambia, China's ties are historically strong, dating back to the construction of the railroad linking Tanzania and Zambia, and the Zambian government is close to Beijing. But Chinese business people are often accused of being insular and sometimes exploitative.

India's long history with Africa

Given its status in many quarters as leader of the postcolonial world and in the anti-apartheid struggle, its English-language heritage, and its historical trading ties across the Arabian Sea, India has ties that are broader and deeper – a point stressed by Indian officials.

India was a key player in South Africa's anti-apartheid struggle, and Indian traders and small-business owners have long been ubiquitous in the region.

The Indian vehicle firm Tata launched its African operations in 1977 from Zambia, where Tata trucks and buses still dot the roads.

"There is a deeper infiltration into the macroeconomic fabric of the continent," notes the World Bank's Broadman. "The Chinese operate as enclaves on the African continent."

But Indians and Africans of Indian descent are not immune to xenophobia and charges of exploitation.

Before the Zambia's 2006 presidential elections, opposition leader Michael Sata lashed out at alleged exploitation by Chinese investors – but also threatened to expel Indian and Lebanese investors.

Indeed, Mr. Seshamani argues that while China likes to gamble, Indians often worry about the potential for another backlash like the mass expulsion from Uganda in 1972.

As India tries to change the dynamic in Africa, it needs to focus on its private entrepreneurs and stress that it is not out to pillage the continent, says Rajan Kohli, deputy secretary general of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry in New Delhi.

"If you try to follow China, you will not succeed. They have more resources to give, and [as a democracy] our decision-making is very slow," he said. "We have to play to our strengths."