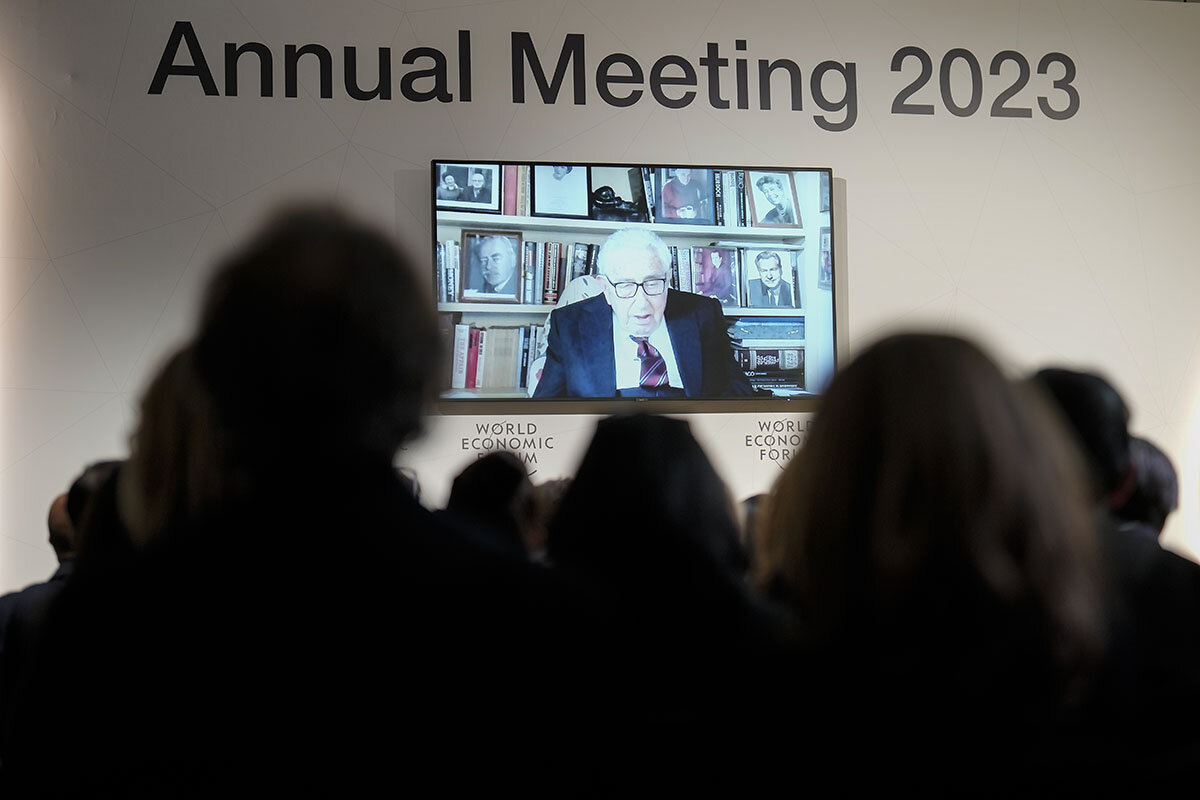

At 100, Henry Kissinger asks tough questions of America

Loading...

| London

Henry Kissinger turned 100 last weekend, warning, with undimmed fervor, of two contemporary threats to an increasingly unstable world: the standoff between America and China, and the growing power of artificial intelligence.

Yet how those challenges might be met could well hinge on a deeper question that Mr. Kissinger first flagged three decades ago: how the United States chooses to engage in a “new world order” that it can no longer design or dominate, as it did during the years following World War II.

What does America, still the leading power, want in the world? Can it break out of its “historical cycle of exuberant overextension and sulking isolationism,” in Mr. Kissinger’s words?

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onHenry Kissinger, 100 last weekend, posed America’s key foreign policy conundrum 30 years ago. The U.S. can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it. That remains unresolved.

And, beyond dealing with inescapable crises, can any U.S. president forge and sustain a cohesive foreign policy, now that the post-World War II bipartisan consensus in Washington has collapsed?

Mr. Kissinger posed all those puzzles in his 1994 book, “Diplomacy,” which I was rereading as he was blowing out his birthday candles.

He wrote it after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But the “new order” that he envisaged – messier; less tractable; in which influence is shared with China, a possibly “imperial” Russia, Europe, and India – is still being born.

And with America’s rivals and allies all watching keenly, the U.S. has yet to resolve the core conundrum that Mr. Kissinger identified in his book: that in navigating this evolving new order, “the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it.”

President Joe Biden would argue, with some justification, that – after the “exuberant overextension” of George W. Bush’s 2003 Iraq War and the “sulking isolationism” of Donald Trump – he is showing the kind of international engagement that a changing world demands.

As Exhibit A, he would probably point to Washington’s response to Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine – making America the indispensable leader of a policy that has been carefully coordinated, and jointly implemented, with U.S. allies in Europe and beyond.

Yet the centenarian Mr. Kissinger was right, in pre-birthday interviews, to single out two key policy challenges now posing a stress test for Mr. Biden’s foreign policy approach.

First, China. Its assertiveness, power, and influence have grown exponentially since the 1990s. Unlike the Soviet Union during the Cold War years, it is also a major world economic force, second only to America.

Under successive U.S. presidents since early this century, U.S.-China ties have been getting chillier and more confrontational.

And now, unlike U.S.-Soviet ties, they’re being hampered by a near-total absence of regular contacts between senior political and military officials in Beijing and Washington.

The challenge for Mr. Biden, especially amid rare bipartisan enthusiasm for a tougher and more protectionist economic policy toward Beijing, is to find a way to avoid leaving the world’s two major powers without sustained and trusted channels of communication.

That’s where Mr. Kissinger is right to highlight the importance of artificial intelligence – which, if unregulated and unconstrained, he fears could become the 21st-century equivalent of the nuclear weapons threat during the Cold War.

In Mr. Kissinger’s view, it’s in everyone’s interest – America’s, China’s, and the wider world’s – for Washington and Beijing to work together to try to put AI guardrails in place, as America and Russia did with nuclear agreements in the less complex geopolitical landscape of the Cold War.

Given the tension and mistrust in U.S.-China ties of late, that may not be easy. Yet, there are growing signs of concern on both sides of that divide about AI.

A number of leading Western technology industry figures this week declared that mitigating AI’s risks should be made “a global priority” on a par with preventing nuclear war. And on Tuesday Chinese leader Xi Jinping called for “dedicated efforts to safeguard ... the security governance of internet data and artificial intelligence.”

Mr. Biden does seem to share Mr. Kissinger’s view that America needs to engage with its Chinese rival, especially on issues neither can solve alone. Indeed, the U.S. president has been making that argument to Beijing as he seeks to revive communication and cooperation despite the increasingly confrontational tone of U.S.-China relations.

But whether the Biden administration’s vision of U.S. engagement in a changing world lasts could depend on one of the still-unresolved challenges Mr. Kissinger wrote about in the 1990s.

It’s the lack of the kind of domestic consensus about America’s role in the world that U.S. presidents enjoyed in the post-World War II years.

That bond was damaged by the Vietnam War. In recent years, it has been eroding further.

Repairing it is likely to prove especially hard with the approach of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Already, some voices in the Republican Party, notably its current presidential frontrunner, Mr. Trump, have questioned America’s active support for Ukraine.

All of that has been feeding uncertainty among both allies and foes over just how durable the Biden administration’s reengagement of America in world affairs will prove.

It seems clear that Mr. Biden has broadly accepted Mr. Kissinger’s bottom-line analysis: that the United States can neither withdraw from the world nor dominate it.

But that is less obviously true of Mr. Trump, President Biden’s predecessor, and, conceivably, his successor.