Biden’s democracy drive goes after global ‘swing states’

Loading...

| London

They’re the new swing states, but not the kind that sway U.S. elections.

They’re the world’s swing states, with an important say in two international geopolitical contests of critical importance to the United States: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the tussle between Washington and Beijing over their rival visions of the 21st-century world.

Wooing these countries is presenting the U.S. with a delicate and daunting diplomatic challenge.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn his global campaign to strengthen democracy, President Joe Biden finds he needs to enlist some allies with dubious democratic credentials.

Dozens in all, and widely varied, they feel no imperative to come down on America’s side. Brazil, South Africa, and India, for example, are all members of the so-called BRICS economic partnership alongside China and Russia. In the Middle East, traditional U.S. allies such as Saudi Arabia have been deepening their ties with Beijing and Moscow.

And while America’s core allies in Europe and Asia share President Joe Biden’s view that today’s world faces a straightforward contest between democracy and autocracy, many swing states dismiss this framing as unhelpful, even hypocritical.

That has forced the Biden administration to find a different strategy. Washington is toning down talk of defending democracy, in favor of a realpolitik focus on bolstering ties and developing areas of clear mutual interest.

Mr. Biden is not happy to trim his diplomatic sails. Helping democracy prevail over autocracy has been a centerpiece of his foreign policy.

But by selectively muting that message to swing states, he’s hopeful of making a virtue of the fact that they are still open to persuasion. They have an existing relationship with America. And while many have indeed also been developing closer ties with China and Russia, none seems minded to become full-scale allies of either autocracy.

Ultimately, Mr. Biden has concluded that his overriding goal – a world tilting not toward autocracy, but democracy – will best be served by deeper relationships with the swing states.

Can Washington foster such ties?

The administration’s approach to one major swing state, India, illustrates the commitment and careful calibration it is bringing to the task.

With 1.4 billion people, India is the world’s second-most-populous country. It sits to the south of the formerly Soviet Central Asian republics and shares a periodically contested border with China.

India’s economy is one of the fastest growing in the world, giving New Delhi increasing diplomatic prominence. Later this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is due to host the annual G-20 summit.

India is a democracy. Yet China is a major trading partner. Since the start of the Ukraine war, India has also bought hugely increased quantities of oil from Russia and brushed aside calls to condemn Russia’s invasion.

And while democratically elected, Mr. Modi has promoted a Hindu-nationalist brand of politics that discriminates against Muslims and other minorities, constrains civil society, and has led to the arrest and prosecution of journalists and critics. Last month, an Indian court sentenced opposition politician Rahul Gandhi to two years’ imprisonment for having suggested that the prime minister was corrupt.

Democracy watchdog Freedom House rates India only “partly free.”

The Biden administration’s navigation through such issues has illustrated its readiness to turn the occasional diplomatic blind eye in its dealings with key swing states.

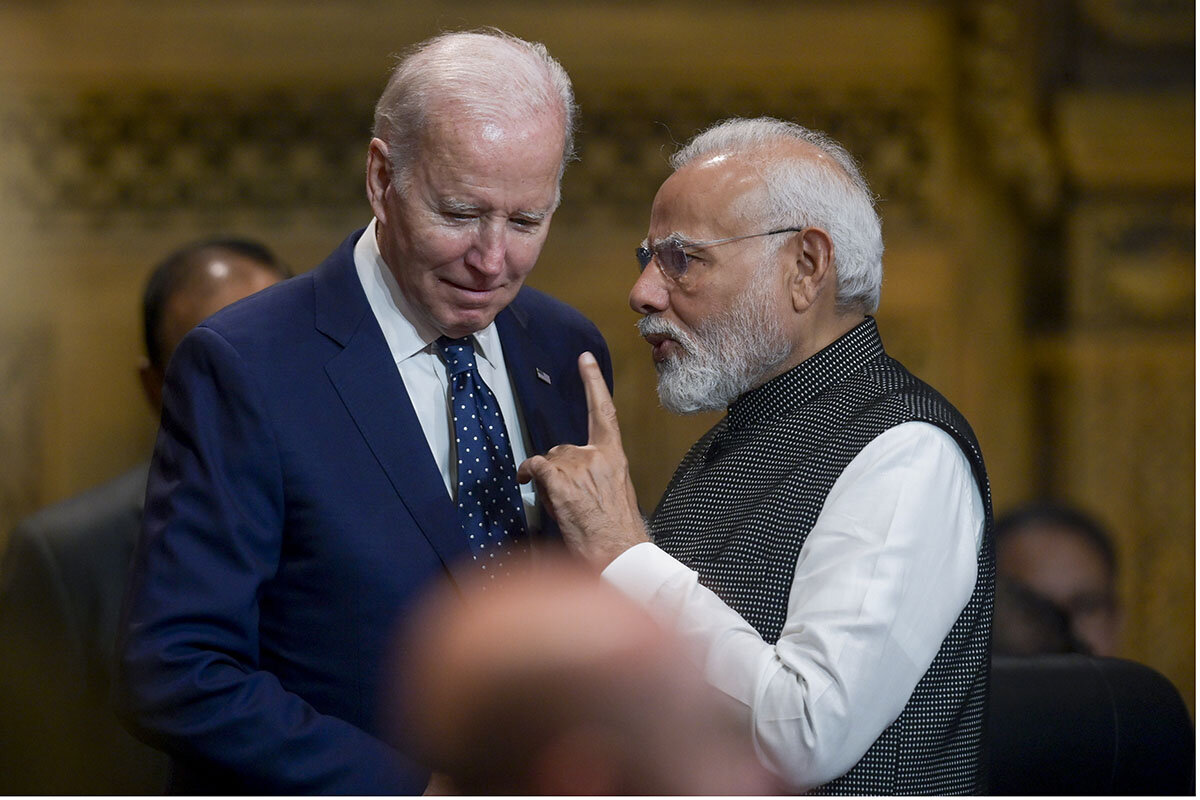

Mr. Modi was a prominent guest last week at President Biden’s second Summit of Democracies. As for the Gandhi verdict, a brief State Department statement said only that Washington was watching as the case went through the courts, and had engaged with India “on our shared commitment to democratic values – including freedom of expression.”

The major focus remained on strengthening relations.

Ahead of the democracy summit, Mr. Biden joined Mr. Modi in extolling the “historic purchase” by Air India of 200 Boeing airliners. Trade is expanding, reaching roughly $120 billion last year, edging the U.S. ahead of China as India’s leading trade partner.

Washington has also been strengthening security ties through India’s membership in the so-called Quad, alongside the U.S., Japan, and Australia, and is stepping up cooperation on strategic technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computers.

It is not that Mr. Biden expects India to reverse course on Ukraine, or to dramatically pare back ties with China. He hopes, rather, that a deeper relationship will embed a sense of shared interests and benefits that might lead, over time, to a more broadly shared understanding on major world issues.

But as Mr. Biden reaches out to swing states, he’ll know there is no guarantee that the uncomfortable trade-offs involved will yield such benefits.

That has become clear in Saudi Arabia, a traditional U.S. ally still critically reliant on Washington for its security, but which has recently been dramatically strengthening its ties with Russia and China.

Last year, Mr. Biden set aside his sharp public criticism of Mohammed bin Salman’s human rights record, in order to meet the Saudi leader and reemphasize the countries’ shared interests. The hope was that the kingdom would increase oil output to help offset the effects of the Ukraine war.

Instead, the Saudis and their fellow oil producers announced a million-barrel cut – benefiting not only Saudi coffers but funneling added funds into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war chest. Any lingering hope in Washington of reinvigorating the alliance took a fresh hit last Sunday, when the Saudis announced a further production cut.

With this newly minted swing state, there seems to be no early prospect of the pendulum moving back.