Out of global upheaval, a new Olympic spirit

Loading...

| Boston

Evangelia Platanioti presses her palms and toes into the blue exercise mat in a pushup position, then nonchalantly brings her right leg past her head. In a move that would defy the czarinas of Twister, she proceeds to lift her back foot off the ground and balances a midair split on – get this – one bent elbow.

“Hold on this pose,” says the Greek Olympian into the camera, as her country’s flag flutters in the background. Ducking under her extended calf, she asks, “Can you see me?”

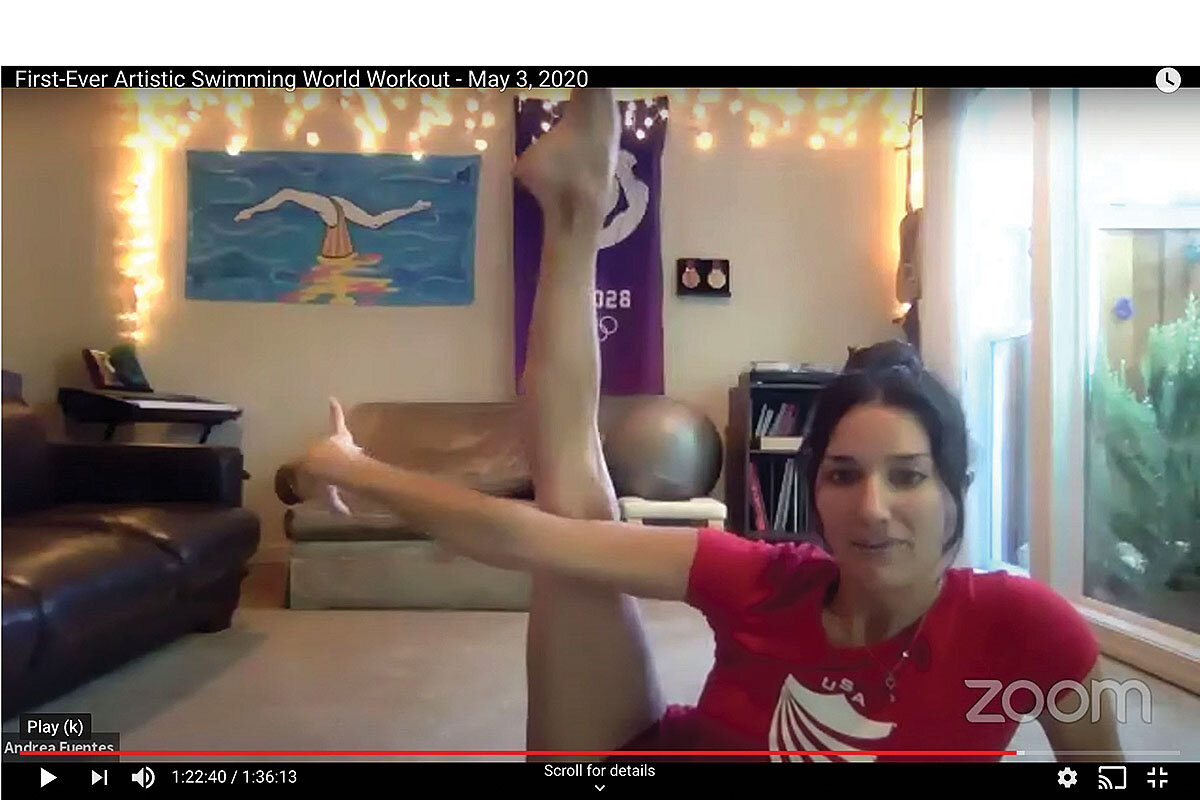

“Yeah, we see you perfect!” exclaims four-time Olympic medalist Andrea Fuentes from her California living room, where the Spanish champion-turned-U.S. team coach is running the first-ever worldwide workout for artistic swimming (formerly known as synchronized swimming) on Zoom.

Why We Wrote This

Many athletes believe the Tokyo Games will be one of the most meaningful Olympics in history, as a pandemic and tumult surrounding social justice spur athletes to rethink their roles in society.

More than 300 swimmers are following Ms. Platanioti’s lead from Austria to New Zealand, where it is 3 a.m. On plush carpets and sun-drenched terraces, they spend 1 1/2 hours copying the movements of more than two dozen of the best athletes in the sport, beamed via a laptop or phone into their homes. Meanwhile, some 6,000 viewers watch live, leaving a running commentary filled with emoji and frequent invocations of their favorite champion’s name followed by “YAAASSSSSS.”

Welcome to being an Olympian in quarantine.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Under normal circumstances, the world’s best athletes would be meeting in Tokyo in late July in hopes of experiencing the pinnacle of what they’ve spent decades sweating and sacrificing for: standing on the Olympic podium, medals draped around their necks, as they listen to their national anthems and the rest of the world looks on rapturously.

Instead, they are coming off what may be the most bizarre few months of training in Olympic history. Now, as they peel themselves off in-home workout mats and head back to the gym or pool, many are doing so with heightened purpose, perseverance, and a global sense of camaraderie that they hope will inspire individuals and nations emerging from COVID-19 lockdowns.

Add in the upheaval surrounding a white policeman’s killing of George Floyd and COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on minority communities, and U.S. Olympians find themselves navigating the world of politics as well as a pandemic. As role models and often celebrities, they’re searching for the right balance between athletics and activism, with many addressing racism in more direct ways – including in their own sports.

From having frank conversations with teammates to challenging the long-standing restrictions of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) on political expression, an increasing cadre of athletes is pushing back on the idea that the Olympic movement can or should be immune to issues convulsing society. Rather, they hope it can become a channel for advancing social change and global unity.

“It’s just tough because we’re dealing with racial injustice and a pandemic at the same time,” says Will Claye, a two-time Olympic silver medalist in triple jump based in San Diego. As a Black man who has experienced racial profiling and discrimination and tense encounters with police, he wants to give others insight into such issues. “What I can do is put together my network, resources – all the blessings I’ve been given – and use it to inspire people, use it to give people knowledge, and use it to make change. I think that’s my purpose.”

Mr. Claye spent the spring mixing creative workouts on a mini-trampoline with efforts such as encouraging young people at an NAACP rally to vote and speaking up at a U.S. Olympic & Paralympic town hall, where athletes pushed for greater political expression. And when he first found out the 2020 Tokyo Olympics would be postponed a year, he wrote a song with the chorus – “Dreams don’t die, they just multiply” – dedicated to all the athletes.

“I think this Olympics will be one of the most prolific Olympics of all time,” he says, because it will be the coming together of nations after dealing with COVID-19, whether that meant not being able to train, losing a job, or knowing someone who died. “We all had to sacrifice.”

The trials of training

Olympic slalom canoeist Sebastián Rossi had been training for months at the Pau-Pyrénées Whitewater Stadium in western France, hoping to qualify for the 2020 Olympics, when the pandemic forced him to return home to Buenos Aires, Argentina.

All he had for water there was a swimming pool. While looking at the palm trees on the edge of the property one day, he had a crazy idea: tether the back of his boat to the tree trunks using a long rubber strap made from the tubes of bicycle tires, and then paddle in the pool against the resistance.

For three months, instead of working out in a whitewater stadium, with its rapids and cascading pools, he’d head out to the pool for 45-minute sessions, paddling vigorously to maintain his strength and balance as fall turned into winter in the Southern Hemisphere. “I won’t go in a swimming pool ever again, even in the summer,” he jokes of his endless time in camp chlorine.

Now that he’s back in the gym and outside in the water in Argentina, he realizes the pool sessions made him stronger – and not just physically.

“I saw it like mental training mostly,” says Mr. Rossi, who shared his workouts on Facebook and Instagram as a way of showing the possibility of getting something good out of quarantine. “Even though it was good to keep fit, for the head it was really important to be able to do 45 minutes in the swimming pool. It makes you tough.”

In a spring survey of athletes, coaches, and other Olympic figures from 135 countries, the IOC found that 56% of athletes were having difficulty training effectively, while fully half were struggling with motivation. But among the dozen-plus athletes interviewed by the Monitor, many recognized that the challenges they faced were not unique to them. From employees juggling jobs and child care to children whose plans for summer camp were dashed, people in all walks of life were having to find creative ways to stay motivated and maintain their equilibrium.

“There’s so many people who are struggling right now, and I’m worried because I don’t have a pool to swim in?” pentathlete Samantha Schultz remembers thinking, as she tried to figure out how to continue training for her sport’s five disciplines – swimming, shooting, fencing, running, and equestrian show jumping. “It’s putting things in perspective – my problems are so small compared to other people’s.”

With the Olympic Training Center closed in her home base of Colorado Springs, Colorado, she found ways to train in her apartment complex. Her husband wasn’t into fencing with her – “he doesn’t really like being a pincushion,” she says – so she parried with a tennis ball, hung on a string in her garage, to refine her footwork. She would also do target practice in her driveway, startling neighbors, she surmises, who didn’t realize that what looked like an oversized pistol was actually a laser gun.

“I’m sure some people do double takes when they drive by,” says Ms. Schultz, whom more people now recognize as their next-door Olympian. “Hopefully I am the cool neighbor with a sword and the laser pistol.”

Across town, javelin thrower Kara Winger and her husband, former discus thrower Russell Winger, have designed an elaborate backyard setup to help her prepare for her fourth Olympic Games.

“The first month of quarantine was much more low-key as far as working out at home,” says Ms. Winger, who initially used kettle bells and other small weights – as well as her yellow Lab, Maddie, who is trained to sit on her back while she’s doing planks. “When it was clear it was going to last a lot longer, I was like, ‘We have to get a little more serious about the home gym.’”

Her husband constructed a cable running from the top of their house down to the back fence. He repurposed a small metal pipe from a cupcake stand he built for their wedding to serve as a “javelin” she could throw up the cable to simulate the action required in competition. A set of transportable parallel bars helps her work on shoulder stability, and she has a new weightlifting bench, which he welded and upholstered.

In addition to the training challenges, the quarantine has prompted some athletes to reflect on their role in society.

Two-time Olympic gold medalist Vincent Hancock, who qualified for his fourth Summer Games in skeet shooting just before the shutdown, has long been wanting to have a greater impact. So in addition to home-schooling his two young daughters and remodeling a home bathroom, he has pulled together a grant proposal for a shooting park in Fort Worth, Texas, to welcome more young athletes into the sport.

Mr. Hancock, who once served in the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit, believes sports can help turn lives around.

“What I’m doing by creating this shooting park is showing people that they can do and accomplish anything they can set their mind to,” he says. “So they can see someone who truly loves and is passionate about what they do. I think that can be the biggest mode of change that I can present at this point.”

New voices for racial justice

Many athletes and sports administrators have been using their sizable social media platforms to support the protest movement in the wake of Mr. Floyd’s killing as well.

On June 2, Sarah Hirshland, chief executive officer of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, tweeted, “The USOPC stands with those who demand equality and equal treatment,” and linked to a letter she’d written to U.S. athletes.

That didn’t sit well with Gwen Berry, one of the best hammer throwers in the world. After winning gold at the Pan American Games last August, she had been put on yearlong probation by the USOPC for raising her fist toward the end of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in a salute reminiscent of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics.

“I thought that was the pinnacle opportunity for me to let the world know where I stood and who I stood for,” says Ms. Berry, who grew up in Ferguson, Missouri, and marched with those protesting the 2014 killing of Michael Brown, a Black 18-year-old, by a white police officer who was never indicted. “I definitely did not know what I was getting myself into.”

The video went viral, and Ms. Berry says she started receiving death threats. She recalls people telling her to “go back to Africa, go back where you came from.” She also lost 80% of her sponsorship income, which included a major reduction in a USA Track & Field Foundation grant that she had received for years. “This is why athletes do not protest,” says Ms. Berry, who adds that she likely will have to start working soon to make ends meet – maybe at a mall near her home in Houston, or as a personal assistant to an executive. “The first thing that happens is your financial stability is taken away.”

(Race Imboden, a fencer who is white and who knelt on the podium in Lima after his team won gold, was also put on yearlong probation.)

After Ms. Hirshland’s comments, Ms. Berry shot back with a tweet of her own: “I want an apology letter .. mailed .. just like you and the IOC MAILED ME WHEN YOU PUT ME ON PROBATION .. stop playing with me.”

In a phone call between the two women facilitated by USA Track & Field CEO Max Siegel, Ms. Hirshland explained her decision but also apologized and heard out Ms. Berry, later tweeting: “Gwen has a powerful voice in this national conversation.” Several days later, Ms. Hirshland announced the creation of an athlete-led group “to challenge the rules and systems in our organization that create barriers to progress, including your right to protest.”

Numerous athletes have called for the USOPC to lift Ms. Berry’s and Mr. Imboden’s probations, and to challenge the IOC’s Rule 50, which bans demonstrations and “political, religious or racial propaganda.”

The IOC Athletes’ Commission introduced updated Rule 50 guidelines in January, which, while allowing athletes to express their views on social media and at press conferences, ruled out specific forms of protest such as kneeling, hand gestures, and the wearing of armbands. It explained that “the example we set by competing with the world’s best while living in harmony in the Olympic Village is a uniquely positive message to send to an increasingly divided world.”

In late June, the USOPC’s Athletes’ Advisory Council demanded that the rule be abolished. “Athletes will no longer be silenced,” it wrote in a letter also signed by Mr. Carlos, the 1968 Olympian.

“I’m extremely encouraged and extremely proud of a lot of athletes who may be risking a lot to change our country and change our communities for the greater good,” says Ms. Berry. “I’m definitely not alone anymore.”

For Olympic 10,000-meter runner Marielle Hall, the sole Black runner on her women’s distance team at a track club in Oregon, Ms. Berry’s ordeal was something of a wake-up call – a recognition of the need to speak openly about her own experience, which she had been hesitant to do before.

“I feel like in that way I’ve isolated someone like Gwen because I haven’t done the work with people I’m around to try and inform them and to allow them to see me fully,” says Ms. Hall, who wrote an essay for Runners World describing the profound impact the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a young Black man who was shot while jogging through a Georgia town, has had on her. She says she thinks about it every day, on every run.

Black Olympians, who brought home more than a third of Team USA’s 2016 gold medal haul, tell of numerous racial incidents they’ve experienced. Ms. Hall, who attended high school outside her district in a largely white area of New Jersey in order to be able to run track, details in her essay how a mother asked her coach whether one of her parents was white – searching for an explanation for her discipline and focus, which the woman didn’t associate with Black families, Ms. Hall wrote.

Mr. Claye, the triple jumper, says he’s been followed in stores ever since he was a child in Arizona, sees women clutch their purses when they pass him, is frequently asked if he’s in the wrong seat when flying business class, and has had police draw guns on him “for no reason.”

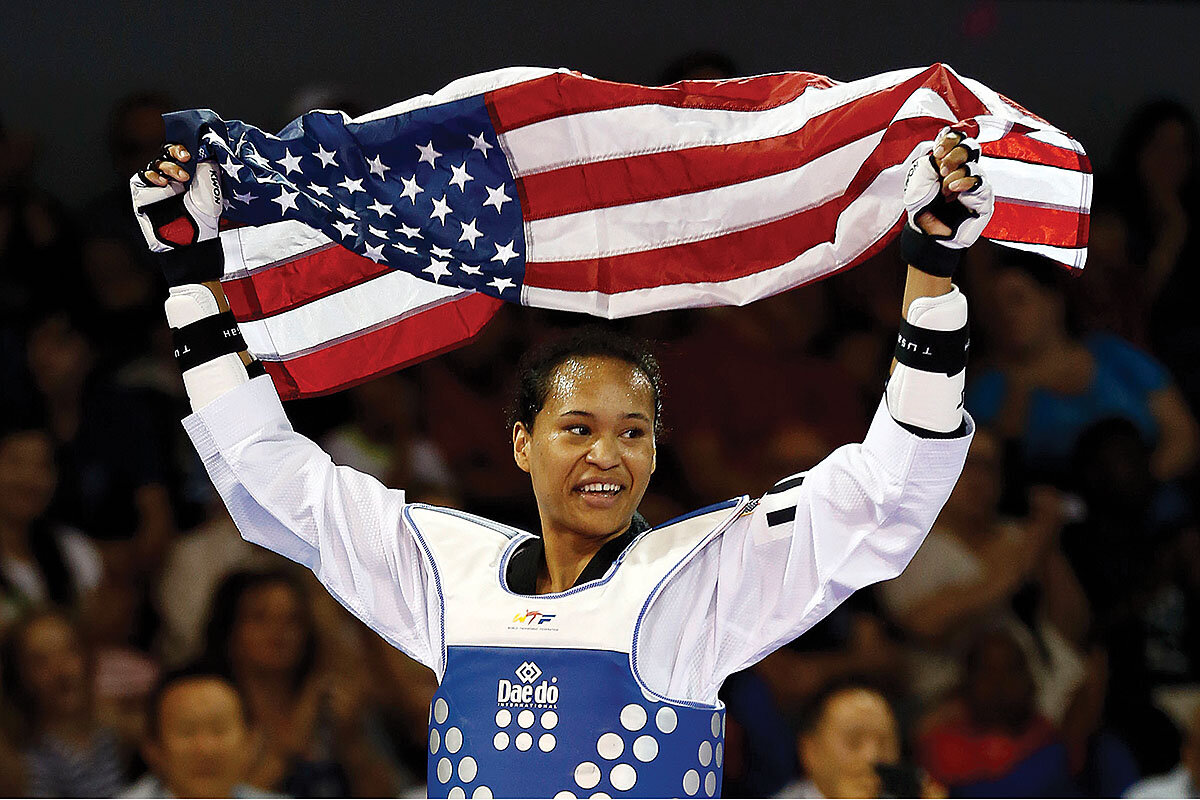

And Paige McPherson, a Black athlete adopted by a white couple in South Dakota, relates having a neighbor threaten to shoot her and her Black sister if they ventured onto his property.

“I choose to be the bigger person than those that deem me as different because of my black skin,” says Ms. McPherson, an Olympic bronze medalist in taekwondo. “My parents instilled in me to be strong in my own being, kind to others, and forgiving, as the Bible says.” She has spoken out on social media against Breonna Taylor’s killing, marched in a Miami prayer walk, and says she understands her fellow athletes’ decisions to protest because of their desire to stop the injustices in America.

But, she adds, the national anthem and raising of the flag is a very delicate subject and has many different meanings to people across the nation. “I also will continue to fight for equality and systemic change but through the use of my own means,” says Ms. McPherson, who has family serving in the Army and National Guard. “They have given their lives to protect and serve our country, which is something I respect and support.”

With the nation’s upheaval playing out in sports as well as on the streets, the usual made-for-TV vignettes about athletes’ path to victory – accompanied by dramatic music and soft, dreamy cinematography – may come across as incongruous. Ms. Berry says there’s no way that athletes’ individual struggles, shaped by their different backgrounds and demographics, can be washed away with “fairy tales and roses” at the Olympics.

“I’m hopeful that the Olympic Games reflect where we are as a country,” says Ms. Hall, who would like to see the Tokyo media coverage showcase more nuanced tales of triumph. “Seeing whole, full people and acknowledging them doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy people doing incredible things and breaking barriers.”

Tight bonds among athletes

In many sports, there’s long been a camaraderie among athletes that stretches across borders. Mr. Hancock once hosted a Chinese skeet shooter who came to train with him and his father in Georgia, and the whole Chinese team later came to Texas, where he took them to a steakhouse. They came face-to-face with 30-ounce tomahawk steaks.

Ms. Schultz says with four- to five-day competitions, the worldwide pentathlon community is quite close. The U.S. team has trained in Germany and Poland, and Egypt and Japan came to the U.S. for workouts.

Now, such esprit de corps is being heightened thanks to COVID-19, from a fun video that international pentathletes collaborated on to the worldwide artistic swimming workout.

“The pandemic [brought] us together like one team – like a world team,” says artistic swimmer Svetlana Kolesnichenko of Russia, a two-time world champion who trains more than 10 hours a day and rarely interacts with other athletes at competitions. She was one of more than two dozen athletes, including Ms. Platanioti of Greece, who spent a month organizing the May 3 worldwide workout via a WhatsApp chat group, which gave them an opportunity to get to know each other as friends rather than just competitors. She has since done Zoom workouts with athletes in Chile, Italy, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, and the U.S., which she hopes to visit one day.

Paula Ramírez of Spain, who was also part of the WhatsApp group, says it was amazing to get to know the Russian champions. The Spanish team also bonded with the Italians, their closest rivals, as both countries were struggling with COVID-19. “It feels really good to be talking with them, ‘Are you OK, are you training?’” says Ms. Ramírez. “We really want to compete with them and beat them. ... [But] in the end we want to compete with someone who is OK.”

Ms. Fuentes, the U.S. artistic swimming coach, told her young U.S. team that Tokyo will be the most special Olympic Games ever if they don’t get canceled.

“It will be very symbolic and it will mean that humanity got over the virus,” she says. “It will be the first time the world will be united after the whole episode. It will be a historical moment.”

Staff writer Sara Miller Llana contributed to this report from Toronto.