How rising food prices are impacting the world

Loading...

Our story begins near Prairie City, Iowa, in the fields of Gordon Wassenaar, who has been coaxing food out of some of the world's richest earth for 57 years. Normally, Mr. Wassenaar is able to harvest about 200 bushels of corn per acre from his land – bin-bursting crops that are sent off to feed people in places as disparate as Michigan and Malawi.

Not this year.

As he walks the 1,500 acres that he farms, Wassenaar occasionally pauses to finger a stalk and peel back the husk, revealing corn that is shriveled and stunted. He figures that the headstrong drought of 2012 will cost him about 40 percent of his harvest.

"It's not that we're gonna go out of business overnight," he says. "But what we're worried about is next year. We've got to get some moisture."

The lean yields on Wassenaar's land, and those of other grain farmers across America's Great Breadbasket, are ricocheting around the world, from Guatemala, to Indonesia, to China. One of the worst droughts in a half century – Wassenaar says it's the most severe he's seen since the year he began farming, in 1955 – is raising prices for some of the world's most important foodstuffs.

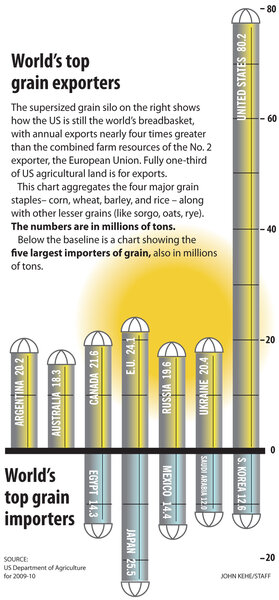

The effects are being exacerbated by churlish weather in other parts of the world – notably in the big wheat-producing areas of Russia, Ukraine, and other countries that hug the Black Sea, where a more moderate drought has hit, as well as in Australia, the globe's No. 2 wheat exporter, where below-average rainfall is expected to reduce the November harvest by more than 10 percent.

As the impact of the droughts works through the global food system, an urgent question looms: How hard are people being squeezed – and will it lead to possible social unrest?

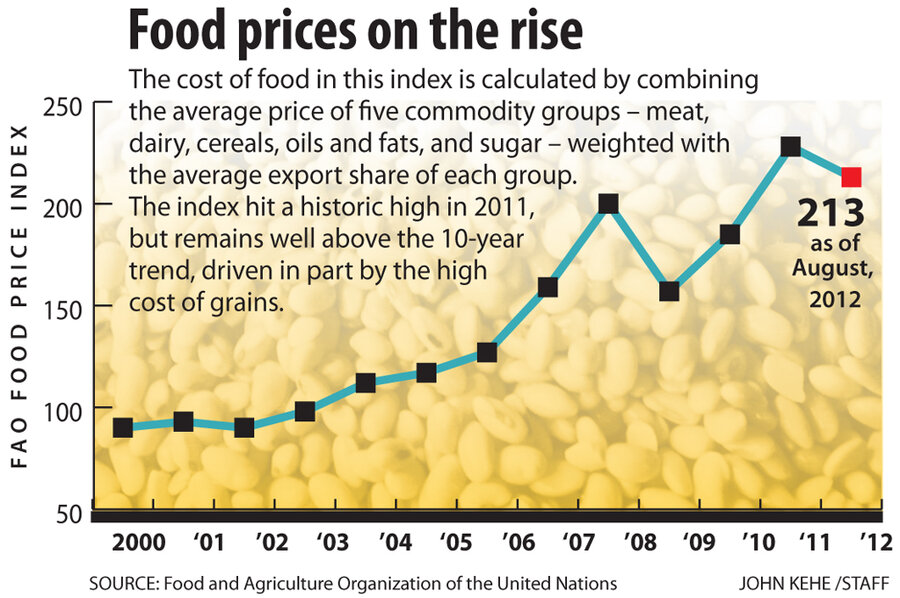

This is no idle consideration. The world has been at this point before, as recently as 2008. At the time, global food prices were soaring, emergency stockpiles were depleted, and, with drought on two continents, little relief seemed in sight.

From Russia, to Panama, to the Philippines, almost everywhere really, governments did precisely the wrong thing. They panicked, rushing into grain markets to stockpile supplies or banning exports. Speculators poured in after them, like lions harassing a herd of antelope, raising prices even further beyond the rational laws of supply and demand.

What followed were bread riots across the developing world from Haiti in the west, through Egypt and Cameroon, and on east to Pakistan and Bangladesh – nearly 30 countries in all. The food crisis of 2008, and a smaller price spike in 2010, also set the stage for the Arab uprisings of 2011 that are still remaking the politics of the Middle East.

Now some see the same danger and disquiet gathering in world capitals as grain prices escalate once again. Except this time there's one key difference: so far, no panic.

Nations around the world have learned some valuable lessons since 2008. More of them have been stocking their larders and preparing for a new global reality driven by increasingly erratic weather and growing demand.

This is not to say the latest droughts are having no impact around the world's dinner tables. Far from it. In countries where a 20 percent increase in the price of a loaf of bread or a sack of rice is often the difference between keeping children in school, setting a little money aside for emergencies, and staving off hunger, the political and social repercussions are still being felt.

Yet 2012 is providing a window into how far the world has come in dealing with the fluctuations of the weather and the interdependence of world food supplies – and how far it still needs to go. The pressures to improve the system will only increase. The planet is growing hotter and drier, and the global population stands at 7 billion and counting.

* * *

Long gone are the days when the world's population was subject solely to the whims of local crops and climate. The green revolution of the 20th century, which generated spectacular increases in grain yields, and the advent of cheap shipping created a global food market that's transformed the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

But it also means that a bad year for farmers in the United States or Russia or Australia can ripple out quickly and become a disastrous year for consumers in Egypt or Indonesia.

Wassenaar knows all about the often vicious vicissitudes of agriculture. He's been through all this before, most notably with the drought in his inaugural year as a farmer, back when Dwight Eisenhower was president and "The Lawrence Welk Show" had just debuted on TV.

He's better equipped to cope with natural disasters today. In 1955, few farmers had crop-failure insurance. Today, 85 percent of them do. Drought-resistant corn had not yet been invented. And Wassenaar and many other farmers have diversified and now also plant soybeans, which have survived the summer in somewhat better shape than corn (though soybean prices are still at record highs because of the dry weather).

But it is corn that is the lifeblood of Iowa and much of American agriculture, not just for producers like Wassenaar, but for feedlots and poultry farms, ethanol refiners, and producers of cooking oils and cookies.

Corn prices have leapt by nearly 50 percent this summer, and US consumers and many farmers are feeling the effects.

The US Department of Agriculture foresees overall grocery prices rising by up to 4 percent in 2013. For some staples, the price rise will be steeper: Shane Ellis, a field specialist for the Iowa Beef Center at Iowa State University in Ames, predicts that choice meat cuts that currently cost $5 per pound will rise to $5.50, reflecting the higher cost of feed.

John Burkel, a farmer in Badger, Minn., is already taking action. He's canceled an order for 12,000 young turkeys. He says taking on a larger flock doesn't make sense economically unless he can raise selling prices. And he repeats an enduring lament of ranchers and poultry farmers who believe they're at a disadvantage without any government protection.

"They have insurance," he says of crop growers. "The livestock guys – we're the ones that gotta feed these animals."

Across the American West, ranchers have been thinning their herds for months. The US cattle herd fell below 98 million head this summer, the lowest level since the early 1970s.

While expensive corn has hurt ranchers and poultry farmers, if they can just survive the next six months, beef and poultry prices should rise, easing the imbalance in their bank accounts. For US consumers, though, all price increases are onerous. The one consolation may be that the proportion of household income spent on food has fallen sharply over the past few decades, to below 15 percent.

But in other parts of the world, the fraction is more improper, with the working poor spending at least 50 percent of their income feeding their families.

* * *

Consider Guatemala, where half of the country's 14 million people live below the poverty line and many struggle to put food on their tables. Throughout history, from centuries past when Mayan cultures flourished on the Yucatán Peninsula until today, corn, ground into meal and made into tortillas, has been the staple.

"It's our most important food. You have tortillas with every meal," says María López, who walks a Guatemala City neighborhood daily, selling hot tortillas door to door.

Two years ago, Guatemalans could buy five tortillas for a quetzal (about 13 cents). Today, a quetzal only buys three tortillas, on average, and other food prices have been surging as well. The government estimates that it costs about 85 quetzales ($10.70) a day to feed a family of four, far more than the minimum daily wage of most people here.

And Guatemala and many of its neighbors in Central and South America are linked to US agricultural production and policy more tightly than ever. "These are countries that are net food importers and overwhelmingly dependent on products coming from the United States," says Fernando Soto Baquero, the senior policy officer for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization's Latin America office.

Between 90 and 99 percent of Central American corn imports come from the US. That dependency was cemented by a US-Central America free-trade agreement, commonly known as CAFTA–DR, which the US Congress narrowly passed in 2005. Since then, the value of annual corn exports to the region has doubled, to about $1 billion.

If the drought were the only factor driving prices, Guatemala and similar governments might have been able to blunt the effects. In theory, they could have bought corn to stockpile when supplies were abundant and prices were cheap, and then released some of the reserves this year, in a time of need.

But they haven't been able to do that because prices were inflated even before the drought struck. That's in part because of something else that happened in 2005: the passage of a law requiring ethanol, made from corn and other grains, to be added in ever increasing amounts to commercial gasoline. Under current law, the US wants to inject 36 billion gallons of ethanol into the fuel supply by 2022.

This year, roughly 40 percent of the US corn crop will go toward the production of ethanol, about 15 percent of the global corn supply. A recent study by researchers at Iowa State University found that the expansion of ethanol production accounted for 36 percent of the increase in the price of corn from 2006 to 2009.

More broadly, Timothy Wise, a food researcher at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., estimates that between 20 and 40 percent of the increase in food prices since 2007 is attributable to the increase in demand for biofuels. Throw in a drought and it's a situation that is "absolutely terrible for countries that consume and are net importers of corn, like Mexico and Central America," says Mr. Wise.

While rising grain prices have hit many poorer countries across the globe, much of Asia has escaped the bulk of the food crisis – because of shrewd planning. Countries like Indonesia, India, the Philippines, and China have used rice reserves – stored up since the last commodity spike four years ago – to curb speculators and head off a price bubble. While wheat, corn, and soybeans have seen price jumps of about 20 percent over the summer, rice has been fairly stable – cushioning the impact for Asian consumers at the grocery store.

"What we learned back in 2008, when we had the blowout in rice prices, was that we could prick that speculative bubble, that hoarding bubble across the system," says Peter Timmer, a professor emeritus of agricultural economics and development at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. "Suddenly, we discovered that the Japanese had 1.5 tons that they were just sitting on, and when it became clear that that could be put into the market, it just stopped [the speculation] dead ... it became clear that just having some kind of reserves to draw on in times of panic can stop the panic itself."

Dr. Timmer laughs as he recalls the recent past, when his analysis was less in demand in the 1980s and '90s, since persistently low grain prices convinced many people that the structural food problem was solved. Sure, there were still famines caused by local crop failures or, more frequently, by war. But high-yielding hybrid grains and an efficient global market seemed to vanquish the wild swings in food prices that had plagued humanity for centuries.

The crisis of four years ago brought his field back into focus, and he's sanguine about the midterm outlook for Asian countries. "They got hammered pretty bad in 2008 and now they're prepared for it," he says.

He notes that he's most worried about Latin America and Africa, where corn is so crucial to the diets of hundreds of millions.

* * *

Sutini, a tofu seller in a market in teeming Jakarta, Indonesia, says she's been forced to raise prices by 50 percent since July because of the rising cost of soybeans. Her sales are down substantially as a consequence.

Sutini's lagging sales are a reminder that not all is well in Asia. Indonesia and some of its neighbors have concerns about rising food prices, too, particularly when it comes to soybeans.

Soy processed into tofu and tempeh (a fermented soy-based cake) is a basic protein for most of Indonesia's 240 million people. And prices have soared, particularly as speculators have poured into the market late in the summer. About 84 percent of Indonesia's soybeans are imported, almost all from the US.

Masito, a homemaker chatting among a group of women beside a trash-strewn river, is one of the Indonesians who's buying less. She's an example of the tens of millions of Indonesians who are both better off than their parents and grandparents, yet still on the knife edge of poverty.

Food prices matter deeply in Indonesia. In 1998, a regional financial crisis sent the economy, employment, and Indonesian currency tumbling, just as an unusually deep El Niño-related drought undercut local agricultural production.

As a result, the price for food, both imported and locally produced, soared and the number of people living below the poverty line doubled in one year, from 33 million to more than 66 million. The economic decline led to mass protests and rioting in many cities, drove Indonesia's longstanding dictator Suharto from power, and created an economic hole that took the country a decade to climb out of.

Social unrest seems unlikely to break out this time around. Inflation appears to be under control, and the country has emerged as one of the great success stories of the late 20th century. In 1970, more than 60 percent of the country's people lived below the government's official poverty line, and average life expectancy was 45 years. By 1998, only 10 percent of the population was below the poverty line, and life expectancy was 65 years.

"Indonesia is now rich enough that they can screw up the management of the food economy in a way that they couldn't afford to years ago," says Timmer.

Still, the price of tofu matters, and Indonesia is going to suffer some economic consequences this year. Already, in July, the government was forced to scrap a 5 percent import duty on soybeans after tofu and tempeh producers briefly went on strike.

The government is also seeking to revive the role of the Bureau of Logistics (Bulog), a government agency tasked with managing food prices that was a hive of corruption and mismanagement under Mr. Suharto. Most of its functions were phased out in the past decade in favor of market-oriented policies.

In early September, the government announced that Bulog would build 28 new food warehouses, and President Bambang Susilo Yudhoyono has been pushing for the agency to regain its control over the prices of rice, sugar, soybeans, and corn.

While that's alarmed international economists who view price controls as doomed to failure and prone to creating market distortion, it's a signal of how urgently Indonesia, like other countries, is looking for answers to the new era of punishing food prices.

"High prices are not that bad if they gradually increase," says Arif Husain, an economist and senior analyst at the UN's World Food Program. "But what hurts people is excessive price volatility, because what that does is affect people's decision-making ability. This is the third price shock in five years."

Tommy Muhasim is one who is suffering. He runs a small tofu factory in south Jakarta – a simple structure that consists of sheet metal draped over wooden pillars. Inside, young men bend over giant concrete stoves fueled by wood-burning fires.

In all, 14 men work here, toiling two shifts a day. When orders are good, the factory runs from 8 a.m. to late in the evening. Since the price of soybeans has risen, however, orders have declined dramatically.

"For us it's hard to raise the price because we pity the people around here," says Mr. Muhasim, in a room with only six bags of beans waiting to be processed. "Many factories like this one have closed because they can't afford to buy soybeans."

* * *

One region analysts will be watching particularly closely for any signs of new upheaval is the Middle East. A recent study by the New England Complex Systems Institute, a Cambridge, Mass.-based think tank, concluded that food prices are a key indicator of political unrest in the region – as evidenced by the Arab Spring, which was triggered in part by widespread frustration over escalating food costs. The authors worry that continuing upward pressures on foodstuffs will unleash a new round of unrest.

Egypt may be the region's canary in a breadbasket. The link between food prices and political stability there extends back to the time of the Pharaohs. Today, Egypt's government is the largest wheat importer in the world, and roughly half of the country's 80 million people rely on heavily subsidized bread from government bakeries. In recent years, the size and quality of the subsidized loaf has been reduced, as the country struggles with a turbulent wheat market and declining tax receipts.

Egypt's foreign-currency reserves now stand at about $15 billion, down from $36 billion at the time Hosni Mubarak was toppled. While economists say the country has substantial wheat reserves, a sustained price shock, if it were to come, would be harder for the country to endure today because of its depleted treasury. For the moment, no one knows what that might mean for a nation trying to build a new, more open political system after decades of military dictatorship.

In more prosperous countries, high grain prices pose risks of a different sort. China, for instance, is home to 1 billion people but just 10 percent of the world's arable land.

Food imports there have surged in recent years. In the first half of 2012, Chinese grain imports grew by 40 percent, to 41 million metric tons. Though the vast majority of China's food is still produced at home, the recent jump in demand adds to the growing competition for global grain supplies and makes Beijing more vulnerable to price shocks.

That has raised concerns among outside analysts that it could lead to an increase in inflation in China, forcing Beijing to further cut economic growth, a move that would ripple around the world. So far Chinese inflation is well under control, with consumer prices rising by just 1.8 percent in July, even as economic growth hummed along at 7 to 8 percent. But there are signs of concern. Farmers in China have dramatically thinned their herds of pigs, the source of the country's most popular meat, as the cost of fattening the animals has surged.

That's been bad news for millions of rural Chinese and could be a harbinger of rising prices for other foods, always a worry for China's Communist Party.

Back in Iowa, in Wassenaar's flint-dry fields, the farmer is lamenting the fickleness of the weather. He hasn't suffered as much as the tofu producer in Indonesia or the tortilla vendor in Guatemala. But he nonetheless thinks there is a better way to offset the impact of natural disasters on American farmers. He wonders if the US should set up its own strategic grain reserve.

"When one area is short, another is going to have to make it up," he says, with simple agrarian pragmatism.

More broadly, Mr. Husain at the UN's World Food Program thinks the countries all around the globe need to be better prepared.

"One thing that is for sure is that weather is playing serious tricks," he says. "You are having much more frequent droughts. In the past five years, we've had three shocks that are drought based and that's something new. Without blowing this out of context, we need to be prepared for serious problems in the future."

• Steve Dinnen in Prairie City, Iowa; Sarah Schonhardt in Jakarta, Indonesia; and Ezra Fieser in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, contributed to this report.