With wildlife corridor, Turkey tackles an ecological crisis

Loading...

| Kars, Turkey

"This is an Armenian plot," mutters a farmer as ecologists explain what may be Turkey's most ambitious wildlife conservation project ever, right in his backyard.

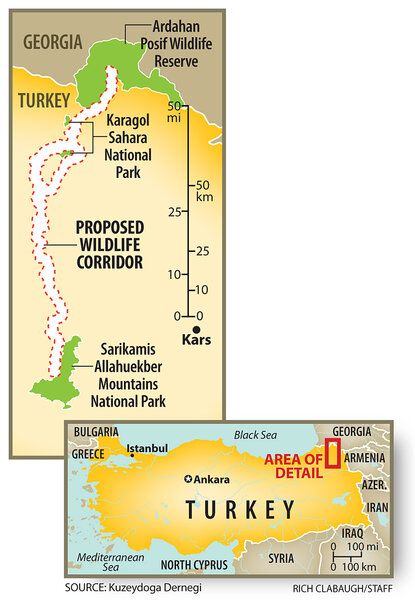

But in fact, the government is behind it. This summer, officials expect to begin the reforestation of a 58,000-acre corridor of land that will connect the isolated Sarikamis National Park and its shrinking population of wolves, bears, and lynxes to a swath of territory in the Caucasus.

In a country where environmentalists are often greeted with official hostility and public indifference, the plan has generated rare optimism among scientists warning of an impending ecological crisis.

"This is the biggest landscape-scale active conservation project ever undertaken in the country," says Cagan Sekercioglu, a professor of biology at the University of Utah who proposed the corridor. "We're hoping this will reduce human-predator contact and encourage these animals to access much larger and more resource-rich forests along the Black Sea and Caucasus."

But near the route of the corridor, which will run close to the border with Turkey's historic enemy Armenia, ecologists got mixed reactions from villagers. "Why can't the government just fence the wolves inside the park?" asked one sheep farmer.

Onder Cirik, projects coordinator for KuzeyDoga, the wildlife charity founded by Mr. Sekercioglu that has spearheaded the corridor project, says that ecological awareness is poor. "People in Turkey have no idea of the importance of biological diversity and of how fast it is being lost."

When it comes to wildlife, Turkey has a lot to lose. Sitting astride one of the world's most biologically diverse nontropical regions, it hosts more known endemic species than all of Europe combined, with some 3,000 plants unique to the country.

New plants and animals are found at a rate faster than one a week. The Taurus ground squirrel was first discovered only in 2007. But as the economy booms – growing an estimated 8.3 percent last year – housing and roads are taking precedence over conservation.

Ecologists accuse the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) of striking down environmental safeguards whenever they conflict with its development plans.

Last August, the AKP abolished a network of independent protection committees, casting into doubt the future of 1,261 smaller nature reserves.

National and international environment groups have condemned a draft conservation law that they say aims to pave the way for development in other protected lands. And ecologists are concerned about a government irrigation and hydropower plan to create 4,000 dams, diversions, and hydroelectric power plants by 2023.

A spokesman for the Ministry of Forestry and Water Works said the government is more alert than ever to environmental issues. "Biological diversity is always endangered where there are human activities and climate change," he said. "But, compared with the past, sensitivity to this problem has increased."

Many Turkish scientists disagree. "Turkey's environmental law and conservation efforts are eroding...," some warned in the December issue of Science. "This has precipitated a conservation crisis that has accelerated over the past decade."

About half of 61 endemic fish species are critically endangered, and 83 of 319 native breeding birds are threatened. In February, Turkey was ranked 121 out of 132 countries for biodiversity and habitat preservation in an annual environmental performance index by Yale University.

Delicate negotiation process

But ecologists must tread carefully. "To pursue projects at protected sites, all NGOs need the permission of the ministry," says Engin Yilmaz, director general of Doga Dernegi, one of Turkey's largest wildlife research charities. "If permission isn't given, you have no legal grounds to carry on activities in nature conservation."

Doga Dernegi learned this the hard way. Last year, Ankara revoked many of its permits to operate in national parks and reserves after it mounted a public campaign against the draft nature law and dam-building policy.

Sekercioglu, who has co-written articles criticizing the government, fears KuzeyDoga could suffer for his outspokenness. "How do I do more good for the Turkish environment?" he asks. "Do I keep quiet and do what I can in northeastern Turkey, or do I look at the big picture and say it's unacceptable? I'm trying to do both."

Some groups have mobilized protests, but with little impact. In one 2010 survey, only 1.3 percent of respondents viewed environment-related issues as a serious concern. "Turks are discovering the consumption society, and they are more than happy with all these things," says Cengiz Aktar, a political scientist at Istanbul's Bahcesehir University. "The government has a major ally in the Turkish public."

In Kars, near the Sarikamis forest, however, one group is optimistic. According to Sekercioglu, a blend of research, patience, and tea-drinking with officials brought successes.

The government has already planned the corridor's course: a 50-mile-long snake of land between 500 and 2,000 yards wide, connecting Sarikamis to much larger forests in neighboring Georgia.

Sekercioglu says about 25 wolves may survive in and around the forest. At least seven have been shot or hit by cars in the past year alone. A radio collar fitted to one young male wolf showed that, since December, the animal had ranged over an area of some 1,189 square miles, more than 13 times the size of Sarikamis National Park.

Sekercioglu hopes the corridor will inspire similar projects, eventually creating a network spanning the country. But, he acknowledges, "it is like turning around a very big ship. It will happen slowly, but we have to keep pushing."