The price of gold: as influential as a global power

Loading...

| Italian Bar Camp, Calif.

Lee Mace knelt on a sun-dappled riverbank in the heart of California's mother lode. For two hours, he'd been taking turns with his wife and their three children, shoveling dirt into a home-built oak box, pouring buckets of water over the top, and rocking it back and forth like a cradle. Gravity carried the heaviest particles through a series of screens to a trap at the bottom, where Mr. Mace removed them to cull by hand in a shallow prospector's pan.

He tilted the pan gently. He squinted into the black silt, as if reading tea leaves. "Look," he said. And then they appeared: a constellation of glowing flecks, none larger than the head of a pin.

It's hard to believe that crumbs like these have obsessed humankind through the ages, but such is the history of gold – indeed, the price of gold, which has become a parallel global power of sorts. Treasure hunters have sought the rare yellow metal since the dawn of civilization. In 3600 BC, gold was first smelted by the Egyptians, who believed it was the flesh of the gods. The Greek poet Pindar called gold "a child of Zeus," adding that "neither moth or rust devoureth it, but the mind of man is devoured by this supreme possession."

Empires have risen and fallen on tides of gold. Driven by gold lust, Spanish conquistadors razed the civilizations of the Aztecs and the Incas, who believed gold came from the sun. Tempted by the promise of gold, explorers embarked on some of the most epic and dangerous wild-goose chases in recorded history. (Though El Dorado has since been confined to the dustbin with Atlantis and Shangri-La, the mythic city endures as a metaphor for the pursuit of impossible wealth.)

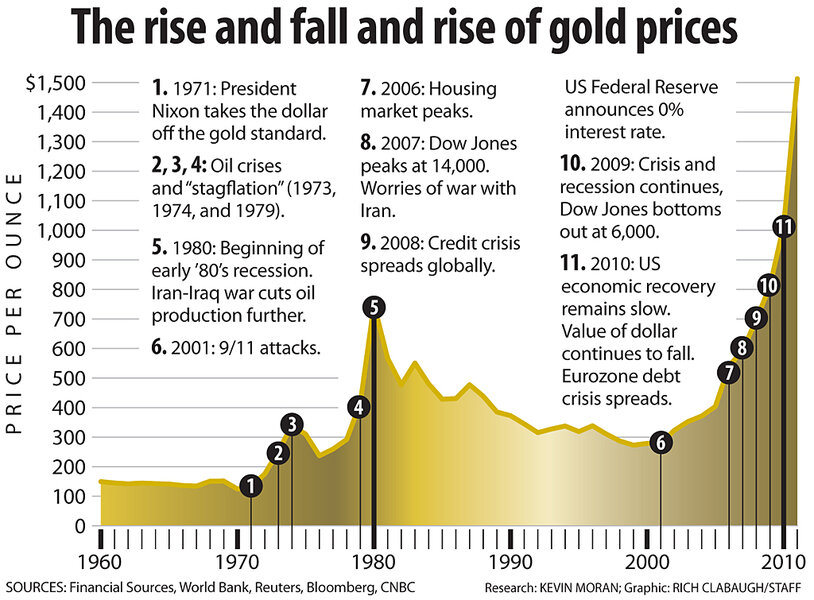

Today, investors herald a new golden age. On April 21, the metal's market value surpassed $1,500 per troy ounce for the first time.

Gold prices have climbed steeply since the turn of the millennium, following two decades of gradual decline after the precious metal's last peak in 1980.

Gold's worth has increased fivefold in the past decade and more than tripled since 2005. And as prices soar, bolstered by private investment and central banks, which started stockpiling gold last year after two decades of selling it off, the metal is poised to remake the world all over again.

"We are at one of these transit points in the history of gold. And I've got a long view: My perspective goes back 6,000 years, not just the past six hours," British historian Timothy Green says with a chuckle. Mr. Green, has studied the yellow metal for more than 45 years and is the author, most recently, of the book "Ages of Gold," published by GFMS, a precious-metals consultancy in London.

"The grass-roots demand for gold – having gold coins under the bed or buried in the garden or wherever you want to hide them – that's coming back," he notes. It has also grown easier to own "paper gold." Gold exchange-traded funds allow investors to bet on gold without actually owning it and have proliferated in markets worldwide since they first appeared in 2003 on the Australian Securities Exchange. These are a far cry from ancient times, when, Green adds, "only the wealthy rulers, the princes, the Tutankhamens, could afford to have gold. It was a symbol of wealth and power."

In any era, understanding gold's worth as a commodity requires some magical thinking. You can't eat it. You can't put it in your gas tank. It won't keep you warm at night. It's not as immediately useful as, say, cattle, which preceded gold as a widely accepted unit of wealth. (Gold's value was originally pegged to the worth of cows. The Latin word for money, "pecunia," comes from "pecus," which means cattle, while the Indian "rupee" is derived from "rupa," or cattle in Sanskrit.)

Gold does have industrial applications – from shielding sensitive instruments against solar radiation in space to dental crowns and the bonding wire in your iPhone – but these accounted for less than one-ninth of the 3,812-ton global demand for gold last year, according to the World Gold Council, an industry trade group. Gold's primary uses, jewelry and investment, are built on abstractions: beauty, symbolism, and scarcity.

Billionaire investor Warren Buffett addressed the fundamental strangeness of gold during a 1998 talk at Harvard University. "It gets dug out of the ground ... then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again, and pay people to stand around guarding it," he said. "It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head."

Here on Earth, folks keep scratching for pay dirt. That's what drew the Mace family, along with more than 100 members of the Gold Prospectors Association of America, to gather last month at Italian Bar Camp, a gold claim in the foothills east of Sacramento. Miners have made pilgrimages to this region since 1848, when flakes of gold turned up in a ditch dug for John Augustus Sutter's sawmill on the American River.

"A couple of years ago we had the gold rush start again," remarked "Klondike Mike" LaBox, one of the organizers at the California outing. His baseball cap was studded with pins made from gold harvested on his 40-acre claim in the Alaskan Panhandle.

"We had people literally selling their farms and their cows and showing up at our camp," Mr. LaBox added. "I told them to go get a job. You can't support a family out here panning for gold."

But "gold fever," as miners call it, can be a powerful contagion.

"Gold has performed exceptionally well over the last decade, and people have a natural tendency to buy into a success story," says Philip Klapwijk, the chairman of GFMS.

While it's true that success creates its own momentum, why does gold do so well to begin with? Traditionally, investors approach gold as a reliable storehouse of value in unreliable times. The events of 9/11 kicked off an era of geopolitical instability. "People are looking for a means to protect themselves," Mr. Klapwijk adds.

Since 2008, international affairs have grown even more tenuous. The financial crisis shook public faith in big banks and governments. The world's three major currencies – the dollar, euro, and yen – have been weakened by a massive housing crash, Greek debt, and a nuclear catastrophe, respectively. When currencies falter, buyers habitually retreat to gold as a hedge against inflation. Against this bleak backdrop, the price of gold is a global anxiety index.

For doomsayers, gold has become a particularly potent talisman: a bulwark against the coming apocalypse. (Nevermind the inconvenience of hauling your hoard around in a Mad Max-style dystopia, let alone defending it from brigands and making small change.)

"We tell people, 'Invest in gold, tangible gold. Put it in your hand. Put it in your safe,' " urged Richard Campbell, a retired deputy sheriff from Tulare, Calif., who wore a 1.72-ounce nugget on a chain around his neck during the prospecting weekend. Should the market collapse, he added, you'll need that gold close at hand, not in a safety deposit box.

"Miners, we're independent people," he said flatly. "We know that's the way it's gonna go."

From dowries to ATMs

Sanat Kumar still remembers the large iron safe set in the floor of his grandfather's home in India.

"The day my sister was born, my mom started collecting gold for her wedding," he recalls. Each year, his parents piled jewelry higher into that safe, growing a future dowry in accordance with national tradition. "They never got to use it, because my sister refused to have an arranged wedding," he adds, laughing. "But it's still in the family."

Decades later, Mr. Kumar is a chemical engineer at Columbia University in New York, and his perspective on gold is more scientific than nostalgic. It's no coincidence that gold is the king of metals, he explains. If history were to unfold all over again, humans would probably still prize the lustrous, sun-colored substance above other elements.

"Gold is totally nonreactive," he explains. "If you take iron and leave it out over time, you get rust, a chemical transformation of iron with oxygen to form something else that's useless. Gold never does that. It's basically inert."

That makes gold virtually indestructible. As a result, nearly all of the 165,000 tons of gold ever mined remains intact. It's no wonder that, starting in ancient times, the dense metal has symbolized eternity. Since gold holds up through repeated recycling, the band on your finger could be made from treasure looted from Egyptian tombs, centuries-old dental work, or nuggets found by forty-niners.

Gold is scarce enough to accrue value, but common enough to circulate, and has been discovered on every continent. It's also tremendously malleable, with a melting point of 1,947 degrees F. Ancient artisans could soften and process it over charcoal fires.

These qualities helped gold evolve into a commodity that is universally prized. And because the metal has such a broad reach today, the past decade's price explosion is causing wide ripples across the globe.

India has changed since Kumar's childhood. Now, some families save face by renting imitation gold jewelry sets for their daughters' weddings. Jewelers have also been pushing "chit funds," encouraging consumers to drop off a pile of rupees each month until they have amassed enough money to buy real gold.

"Here, you will see all jewelry stores packed with people," says Kavita Krishnan, a housewife in Chennai. "I wonder how these people have money to buy jewelry. But then I realize that people have these chit funds. That's what's bringing them into the market."

Gold is to Indians as gasoline is to Americans: the lifeblood of traditional consumer culture. In the past decade, India's appetite for gold – the largest in the world – has risen 25 percent, despite a 400 percent rise in the metal's rupee price.

Demand for gold has also increased in China, where the growing middle class is snapping up jewelry. Inflation fears helped drive bullion investments in China to $4.1 billion in the first quarter of 2011, double the year before. Like many cultures, the Chinese have long associated gold – both the color and the metal – with wealth, lavish celebrations, and power. Gold was the color of emperors and remains a favorite New Year's gift. And since the Chinese government liberalized bullion trading in 2001, coins and ingots – anonymous, discreet, and expected to hold their value – have become the preferred currency for buying favors from officials, to judge by the large number of such officials who have been tried in recent years for accepting bullion as a bribe.

Around the globe, sharp-eyed entrepreneurs are watching for opportunities to profit as gold quickens the public pulse.

German businessman Thomas Geissler unveiled what he says is the world's first "gold ATM" – a bulletproof bullion vending machine called "Gold to Go"– last year in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Since then, he's installed more than a dozen of the contraptions around Germany and the United Arab Emirates. In Las Vegas, there's one at the Golden Nugget Casino. Another arrived July 1 at the Westfield shopping center in London, where it stands alongside a cash ATM and a soft-drink machine, to the bemusement of shoppers.

Mr. Geissler hopes small amounts of gold will replace chocolate or flowers as commonplace tokens of affection. Two-thirds of his buyers are gift-givers, he estimates.

"When you watch the people buying gold at the machine, they're smiling, laughing," he says.

In the United States and Britain, the newest spin on Tupperware parties has a golden hue. Dozens of businesses, bearing such names as "Party of Gold" and "Golden Opportunities," encourage consumers to host "gold parties," where friends sell their old jewelry to a broker while making small talk over drinks and snacks. (Canny guests may realize they're being asked to part with gold for far less than its market value. That margin goes mostly to the company but also to the host, who typically pockets a 10 percent commission.)

Goldline International, the US-based bullion vendor known for retaining the former Fox News talk show host as its enthusiastic pitchman Glenn Beck, has seen its fortunes rise along with the global appetite for gold. At the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, the company had more than 300 employees and boasted $525 million in annual revenues. Now it has more than 400 employees and expects revenues to reach $800 million for the fiscal year ending later this month, says chief executive Mark Albarian.

"People are worried about paper, and gold is the opposite of paper," Mr. Albarian says.

(He's not alone in that view. Back in California gold country, Mace's wife, Kathy, offered a similar lesson in value to her 7-year-old daughter, who won a boot-shaped gold nugget in a contest but looked longingly at the other prizes, which included hats, pins, and patches. "What is money? Paper," Ms. Mace told her. "What is gold? Gold.")

As prices rise, so does the worldwide interest in gold recovery and recycling. In Iraq, jewelers have long worked with salvagers' help to recover "tayeh," or missing gold.

"Salvaging gold dust or very small pieces of gold that might be lost during manufacturing at the goldsmith's workshop is an ancient practice," says Mousa El Aradhi, a Baghdad jeweler. "There are people specialized in recovering gold from the dust on the floors, on the workshop tools."

Recently, salvagers have been striking out on their own, scouring Baghdad sewers for trace amounts of gold that has escaped down jewelers' drains.

Recycling is big in Japan, where workers extract growing quantities of gold from "urban mines": dumps of old electronic equipment and industrial waste. (Each year, the Japanese replace some 20 million mobile phones, making these discards a particularly rich source.) At one waste facility in Nagano, near a cluster of electronics factories, workers recover 70 ounces of gold each year from industrial sludge emitted by neighboring electronics factories. Experts believe that, if all the opportunities to salvage and recycle gold were exploited, natural resource-poor Japan would be among the world's top five gold-producing nations.

The high human cost of gold

In 1511, King Ferdinand of Spain famously declared, "Get gold, humanely if possible – but at all costs, get gold!"

His conquistadors glutted themselves with gold in the New World, but at a heavy cost that included, in the words of 19th-century American historian William H. Prescott, "the most atrocious acts of perfidy on the record of history."

For all its luster, gold's past is paved with bones. In the 1st century BC, Greek scholar Diodorus Siculus described the suffering of Nubian miners under the Egyptians. "[T]hough by their labor they enriched their masters to an almost incredible extent, [they] did it by toiling night and day in their golden prisons," he wrote. "They were compelled by the lash to work so incessantly that they died of the hardships in the caverns themselves had dug."

Gold's glimmer still lights a trail of devastation. Extracting a single ounce from the earth generates an estimated 30 tons of waste, more than any other metal. Cyanide and mercury are often used to leach gold from ore, a process with toxic consequences. In 1995, hundreds of thousands of gallons of cyanide-laced waste water broke through a dam at a gold mine in Guyana, tainting the Essequibo River, the nation's main water source. Five years later, a gold mine in Romania leaked cyanide into a Danube River tributary. The poison flowed all the way to the Black Sea. It killed 1,000 tons of fish.

In March, three men were burned alive by a vigilante mob in La Rinconada, a mining town in southeast Peru. The victims were accused of stealing gold from a local storage facility, police told the EFE news agency. Gold is the nation's top export, but it's also led to no shortage of problems, as illegal miners blast away tons of earth with high-pressure hoses, creating brown gashes visible in satellite photographs.

Victor Zambrano, who heads a nonprofit group supporting Peru's Tambopata Reserve, said the high price of gold and failure of Peruvian authorities to crack down on illegal mining in the southeastern Amazon is causing massive and irreversible destruction there.

"We are losing forested areas at an alarming rate, which has not slowed despite moves by the government," Mr. Zambrano says. "The people involved in illegal mining know that the government may act, but that any action will be shortlived and things go back to normal quickly."

Illegal mining is inching toward the Tambopata Reserve, which was created in 2000 and famed for its biodiversity. Covering 678,484 acres, it is home to 7 percent of the world's bird species and 4 percent of mammals, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

There's growing pressure to make gold greener and more humane. The environmental advocacy group Earthworks is stepping up efforts in its "No Dirty Gold" campaign. In June, the World Gold Council released a draft of production and refining standards for "conflict-free gold" in an effort to keep gold from financing war, particularly in the Congo.

The global economy, however, isn't cooperating: The higher gold's price, the more extreme measures people will take to get it.

Gold's standard-bearers

"I think, within the next five years, the dollar will be relinked to gold," says Steve Forbes, publisher of the magazine that bears his family name. "In this imperfect world, gold is the thing that has the most stable, intrinsic value."

But going back to the gold standard, Mr. Forbes acknowledges, is a somewhat heretical notion. "You don't want to be seen as a kook, so it's still in the closet," he adds.

The gold standard acts like a financial straitjacket. It restricts a nation's economic flexibility by limiting regulation of the money supply. Keynes called it a "barbarous relic." Most modern economists agree.

In recent months, however, returning the dollar – the keystone currency of the global economy – to a gold standard has become a cause célèbre for tea partyers and others disaffected by American government. They envision gold as a harsh disciplinarian, a schoolmarm menacing the Federal Reserve with a paddle. Binding the currency to the rare metal, they argue, would curtail spending, restore fiscal responsibility, and ward off inflation.

In a gesture of support, legislators of more than a dozen states have pushed to make gold an alternative currency for a variety of transactions. In Utah, US-minted gold and silver coins became legal tender in May, though it's commonly understood that their market worth greatly outstrips their face value, which means no one will actually use them to buy anything. That seems almost fitting, since gold's value has always been more symbolic than tangible.

Though it's hard to picture gold as the future economic compass, the metal readily points to past lessons: When people lose faith in their fellows, they reinvest it in gold.

Back in California, Philip Mike Murphy was prepared for that new world order. Four weeks after the entrepreneur and former mine foreman from Tehachapi, Calif., brought to market his invention – the Mine-Tech Ultra Gold Processor, a dry washer that strains gold from dirt – he said he'd already sold two for $1,495 apiece and had at least a dozen potential customers lining up for more. Two of the battery-operated contraptions juddered and chugged beside his RV during the prospectors' outing, where he said five miners had approached him to buy. When asked why people like gold, Mr. Murphy paused. Then he said, "I don't know, to be honest.

"If I were around during the gold rush I'd probably be the storekeeper or the bar owner," he added. "Those guys made the money."

– Ben Arnoldy in New Delhi; Lucien Chauvin in Lima, Peru; Peter Ford in Beijing; Sahar Issa in Baghdad; and Gavin Blair in Tokyo contributed to this article.