What guilty verdict in Silk Road trial might mean for Internet freedom

Loading...

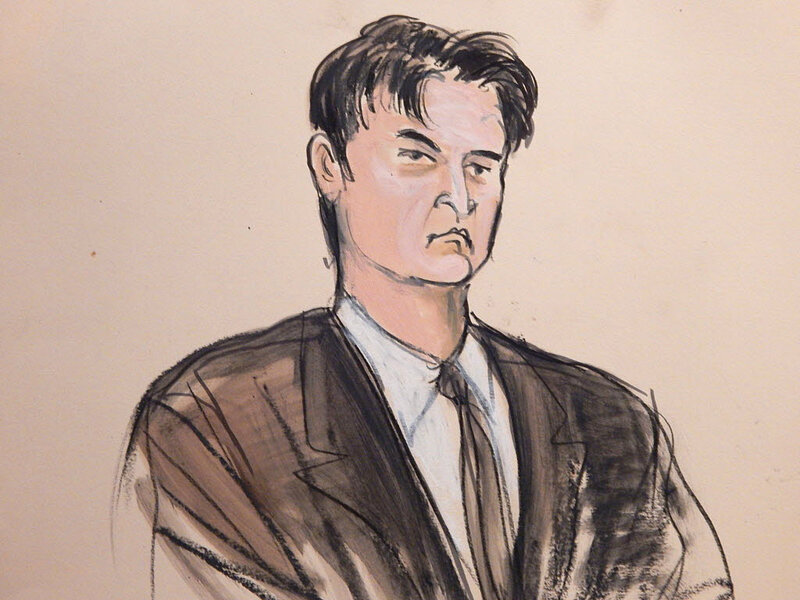

On Wednesday, a jury decided that Ross Ulbricht is the “Dread Pirate Roberts,” the pseudonym used by the architect of the Silk Road underground drug bazaar.

Before it was shut down by the federal government in 2013, Silk Road was considered the largest marketplace for finding illegal drugs online. The site was also used to sell fake IDs and other illegal goods using bitcoin, an online currency that operates with no central authority or banks. The prosecution said that Mr. Ulbricht was a “kingpin” who received a portion of every transaction that occurred on the site.

Ulbricht will be sentenced in May and faces a minimum of 20 years in prison. He could also be handed a life sentence. The defense has attempted to paint Ulbricht as a naïve kid who was framed after his Frankenstein monster grew out of control. It is expected to appeal the decision.

The case is broadly important, experts say, because it could have implications for Internet freedom. It explores not only the legal question of whether a website operator can be held accountable for how his site is used by others but also how the government ferrets out illegal Internet activity. Along the way, the proceedings have provided an unvarnished look at the Internet's dark side, perhaps for the first time.

"What's most interesting about this case is that it is the first case in its enormity involving the Dark Net and it's going to be a wakeup for anyone using the Dark Net thinking they have anonymity. You cannot remain anonymous on the Internet," Darren Hayes, assistant professor and director of cyber security at Pace University, told CNBC.

Ulbricht was arrested after the Federal Bureau of Investigation discovered a server in Iceland that linked him to Silk Road. But how the FBI discovered the server has been a point of contention. Ulbricht’s defenders claim that the government used illegal methods to locate Silk Road, violating his constitutional right to privacy, though a judge denied that line of defense.

The anonymity protections provided by the cryptographic software Tor mean that law enforcement would need to obtain a search warrant to discover the the location of Silk Road's servers, Ulbricht's defenders say. The lack of a warrant taints the evidence found in the subsequent investigation, the defense stated in a memo.

The FBI stated that it located the server due to a misconfiguration of Silk Road’s CAPTCHA system – the string of letters and numbers that helps protect a site from spam. This error inadvertently revealed the server's IP address, the FBI said.

But experts claim that it would be impossible to use the CAPTCHA to find the server. Some suggest that the National Security Agency might have had a hand in locating the server.

“My guess is that the NSA provided the FBI with this information. We know that the NSA provides surveillance data to the FBI and the DEA, under the condition that they lie about where it came from in court,” wrote Bruce Schneier, Chief Technology Officer of Co3 Systems and a fellow at Harvard's Berkman Center, on his blog.

Meanwhile, the idea of charging a website’s operator with wrongdoing when a user conducts illegal activity raises interesting questions about Internet freedom, says Hanni Fakhoury, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

"The main issue, the main Internet freedom issue is at what point are website operators accountable for what happens on their site? In Silk Road, it's an easy case because they were catering to illegal activity. But what is interesting is that you start with easy cases and then you start to go towards some of the borderline cases," he said to CNBC.

In Ulbricht’s case, the jury decided that, as the mastermind behind a site catering to the sale of nefarious content, he should be held accountable. The evidence against Ulbricht, most of which was located on his laptop, was overwhelming and included digital chat records, traced bitcoin transactions, and a diary he kept detailing the tribulations he faced while running the site.

The jury deliberated for under four hours before it found Ulbricht guilty on seven counts, including money laundering, drug trafficking, and computer hacking, among others.