Why did the government spend $10 million to create a new video game?

Loading...

Who says video games make kids fat?

The federal government has spent more than $10 million developing and promoting a video game to combat obesity, according to a report by the Washington Free Beacon, drawing ire from some observers who view it as an example of wasteful government spending.

The video games, financed by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants between 2003 and 2008, have been designed as one method to encourage healthy diet and exercise among American youth. First Lady Michelle Obama's "Let's Move!" campaign, which aims to end childhood obesity in one generation, brought fresh attention to the problem of childhood obesity in the US, as well as criticism from some on the right for what they have called "nanny state" policing.

Former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, the Republican Party’s vice presidential nominee in 2008, has called the first lady’s efforts a “nanny state run amok," a view reflected by other conservatives, including Michelle Bachmann, Rush Limbaugh, and Sean Hannity.

The NIH's video game experiment is likely to draw similar controversy, though the NIH defends it.

“With the increasing rates of child obesity and diabetes, innovative programs are needed that capture children’s attention and permit behavior change messages to get through,” the grant for the video games said. “Serious video games with their immersive stories offer one such promising alternative.”

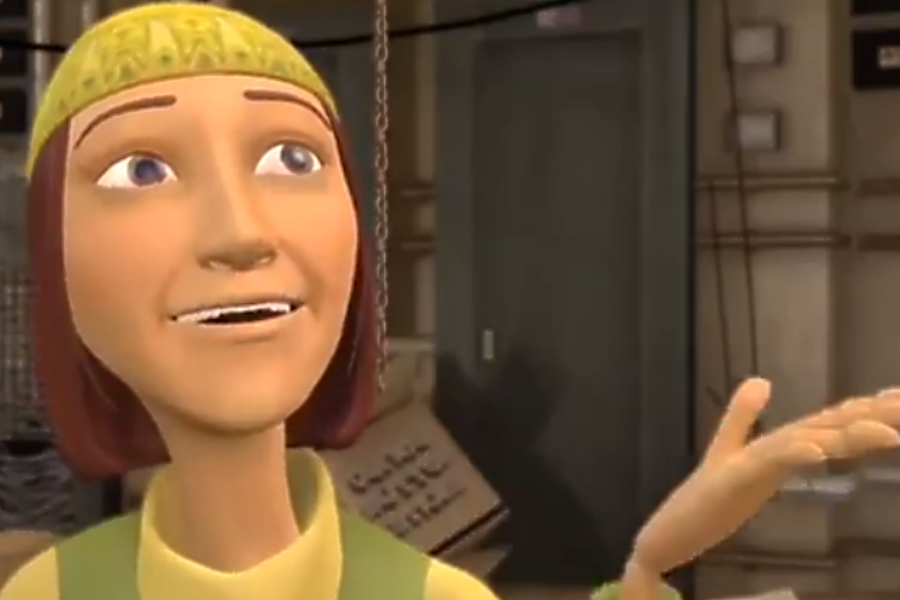

Archimage, Inc., a computer game company, received $9,091,409 to develop the games. One game, called "Escape from Diab," centers on Deejay, a teen who must escape the nightmare fictional city of Diab, where people eat only junk food.

“This is the town of Diab. You can eat all the junk food you want. In Diab, you never have to exercise,” a narrator says over a trailer for the game. “Sound like a dream? It’s not.”

Deejay must teach his overweight friends about healthy eating and exercise to escape the city, which is full of “high-rise vending towers” that give “free access to foods like Lard Chips, Creamy Cakes, Butter Breads, and Etes Burgers."

The video games, which are not available to play online, were tested on some 100 kids aged 10 to 12 to measure their effectiveness.

"Results of the study found that children increased the amount of fruits and vegetables they eat by 0.67 servings, but that playing a video game did not increase their physical activity levels," reported the Beacon.

According to its report, the NIH is now spending $1,760,807 for further research on how the games can fight obesity, through studies being conducted by Baylor College of Medicine.

The NIH has also used computer game developer Archimage to develop at least two other video games: “Nanoswarm: Invasion from Inner Space,” is a game set in 2030 when the United States has a female president and life is “almost perfect,” but kids have to save the planet from obesity and diabetes. “Kiddio: Food Fight” is a mobile game that teaches parents how to feed fruits and vegetables to their kids.

How much does it cost to develop a video game? Estimates range from $10 million to $100 million, according to video game development sites.