Scottsboro Boys: 82 years later, redemption from Alabama

Loading...

The story of the so-called Scottsboro Boys, Depression-era black teenagers who hopped a box car to find work, got into a fight with some white men, and ended the day arrested for the rapes of two white women, is finally ending with a long-delayed chapter of redemption.

The state of Alabama on Thursday granted a posthumous pardon to the last three of the nine men who still had marks on their records. Their sagas, which began in 1931, helped galvanize the civil rights movement and yielded two landmark US Supreme Court decisions.

Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems, and Andy Wright all died decades ago, but their six-year court battle continues to inspire books, songs, documentaries, and a 2010 Broadway musical. The lyrics from one song explain:

"Our story beings one fine spring morning,

March the 25th, nineteen hundred and thirty-one,

on a box car headed for Memphis.

And 9 young boys, 9 complete strangers,

are about to begin the ride of their lives."

After an all-white jury delivered the boys an initial death sentence – after six hours of deliberation, despite a recanted testimony by one of the accusers – the US Supreme Court ruled that blacks could not be excluded from juries on racial grounds, and that all criminal defendants required adequate legal representation.

The men's story also inspired Sheila Washington, a resident of Scottsboro, Ala., who read Mr. Patterson's memoir when she was a teenager, to seek some kind of justice for them.

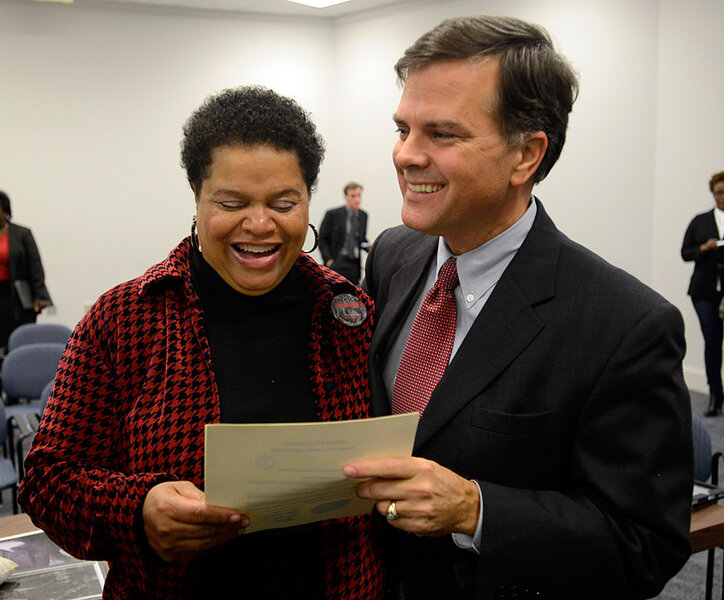

Ms. Washington founded the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center in 2010, and earlier this year she gathered support in the Alabama legislature to pass a law allowing for posthumous pardons of felonies committed at least 75 years earlier. The new legislation was tailored to exonerate the three remaining Scottsboro Boys, who died as convicted felons, and in October, a group of scholars delivered a 107-page petition to the board seeking the pardons.

“Today is a reminder that it is never too late to right a wrong," Republican state Sen. Arthur Orr, who sponsored the bill, told the state parole board Thursday. "We cannot go back in time and change the course of history, but we can change how we respond.”

A three-person panel of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles voted unanimously to approve the measure, in a hearing Thursday in Montgomery.

“This decision will give them a final peace in their graves, wherever they are,” Washington told the Montgomery Advisor.

"[That]'s a nice thought," commented The Week's Emily Shire, on Washington's words. "But the gesture can only be considered too little, too late. Posthumous pardons may give comfort to a town that still bears the scars of hosting one of the most racist and blatantly biased trials in history. But it will never reclaim the years lost by the young men sitting on death row."

The three mens' relatives were invited to attend Thursday's hearing, but none did.

Though all of the men eventually made their way out of prison, many of them never recovered from the trials, their time on death row, and the stigma that dogged them during and after the high-profile, six-year ordeal, Ms. Shire writes. "Andy Wright was paroled in 1943, but when he returned to Alabama he was jailed until 1950. His brother Roy, the youngest of the nine, killed his wife and then himself in 1959. Haywood Patterson was jailed for killing a man in a barroom brawl, and died in prison at the age of 39. Willie Roberson had an IQ of 64 – legally mentally retarded – and the time and date of his death are unknown. Olen Montgomery tried to create a music career, but after struggling, spent his final days drinking away his frustrations."

Courts had overturned five of the men's convictions in 1937, but by the end of their lives, each of the nine had spent between six and 19 years in jail. Norris, the last surviving member of the group, was pardoned in 1976 and died in 1989; he was the only one to receive a pardon during his lifetime.

Accounts differ on how exactly the rape charges emerged. According to Washington, one of the two young women had been banned from crossing state lines, after a brush with the law. When the white men who had scuffled with the Scottsboro Boys sent police to stop the train and arrest them, a sheriff asked the woman on parole why she was on the train. She responded by asking if he was really going to arrest her "after what they did to us," telling the officer that the black boys had raped them.

James Goodman, a professor of history and creative writing at Rutgers University, described to CNN the effect the cases had on the awareness of white Americans. "African-Americans had never stopped agitating for their rights after Reconstruction, but this is the beginning – once again – of an interracial movement for equality that had been stalled between the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the Depression," he said. "Suddenly, white people who just hadn't been paying attention begin to say, 'Holy mackerel, they're going to put nine African-American teenagers in the electric chair?' "

But, said Mr. Goodman, today's criminal justice system is still clogged with racial bias.

"Sadly, our prisons are still full of youngish black people who have been falsely accused of crime," he said. "Your chance, even to this day, of being incarcerated for something that you didn't do are still much greater if your skin is black or dark."

The arrest of the Scottsboro Boys on March 25, 1931, came on the same day when Ida B. Wells, the African-American investigative journalist who spent her life writing about miscarriages of racial justice, and campaigning against lynchings, died while writing her autobiography.

"Neither character nor standing avails the Negro if he dares to protect himself against the white man or becomes his rival," wrote Ms. Wells in 1892.