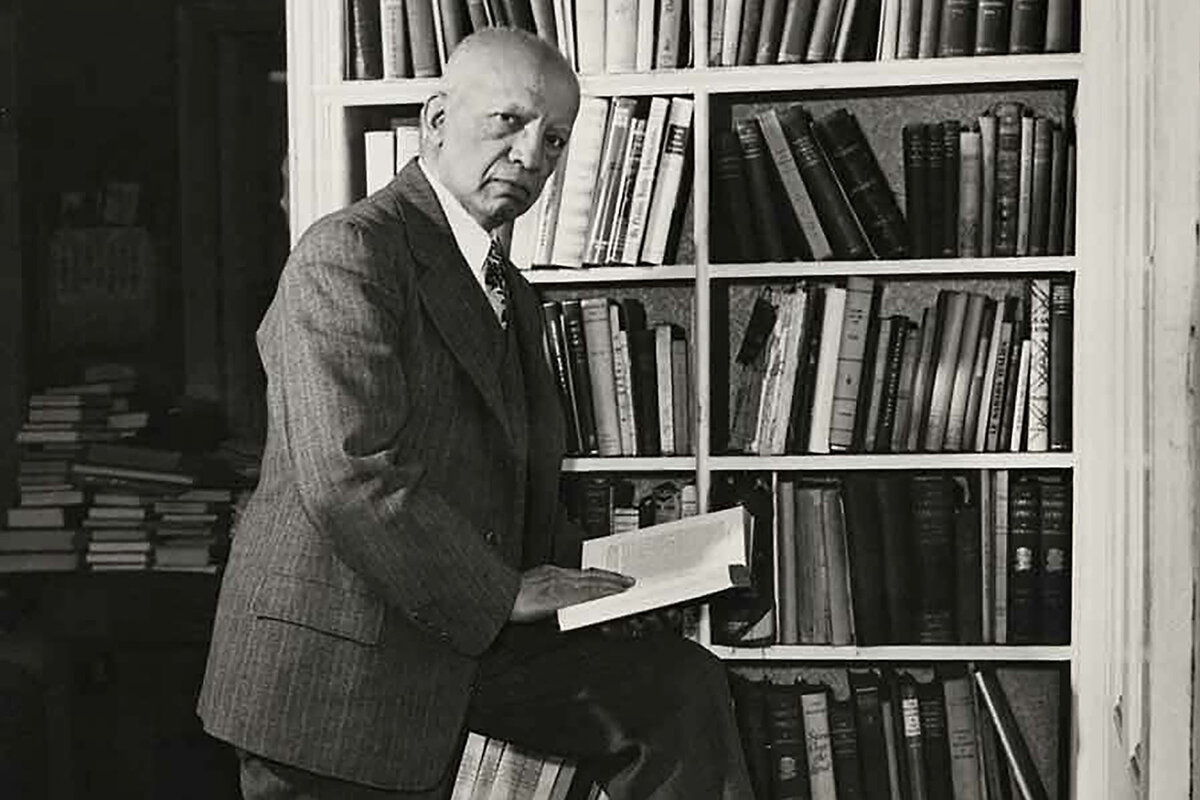

How Carter Woodson became the ‘father of Black history’

Loading...

Some years ago, I made a declaration at a Black history panel that I’m not proud of: “We should get rid of Black History Month.” I wasn’t being anti-Black – quite the opposite. I was drawing on how I had interpreted Carter G. Woodson’s viewpoints on the study of “the Negro in history.”

“Black history wasn’t something to be studied in a month,” I contended, “but should be a part of a greater curriculum.”

In later years, I would have a greater appreciation for the fact that Black History Month is a thoughtful evolution of Negro History Week. Woodson, who is considered the “father of Black history,” founded that commemoration in February 1926 because there were already celebrations at the time that centered around both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOur columnist talks with one of Black History Month’s modern-day keepers about the work it takes to remember the past – and to carve out space for the future.

But Woodson often sought more significant commemoration – and collaboration, which is why he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. On the website of what is now called the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) is an article, “The Origins of Black History Month.” In it, Daryl Scott, a former president of the group, writes that Woodson was “up to something more than building on tradition.”

“Without saying so, he aimed to reform it from the study of two great men to a great race. Though he admired both men, Woodson had never been fond of the celebrations held in their honor,” Dr. Scott writes. “Rather than focusing on two men, the black community, he believed, should focus on the countless black men and women who had contributed to the advance of human civilization.”

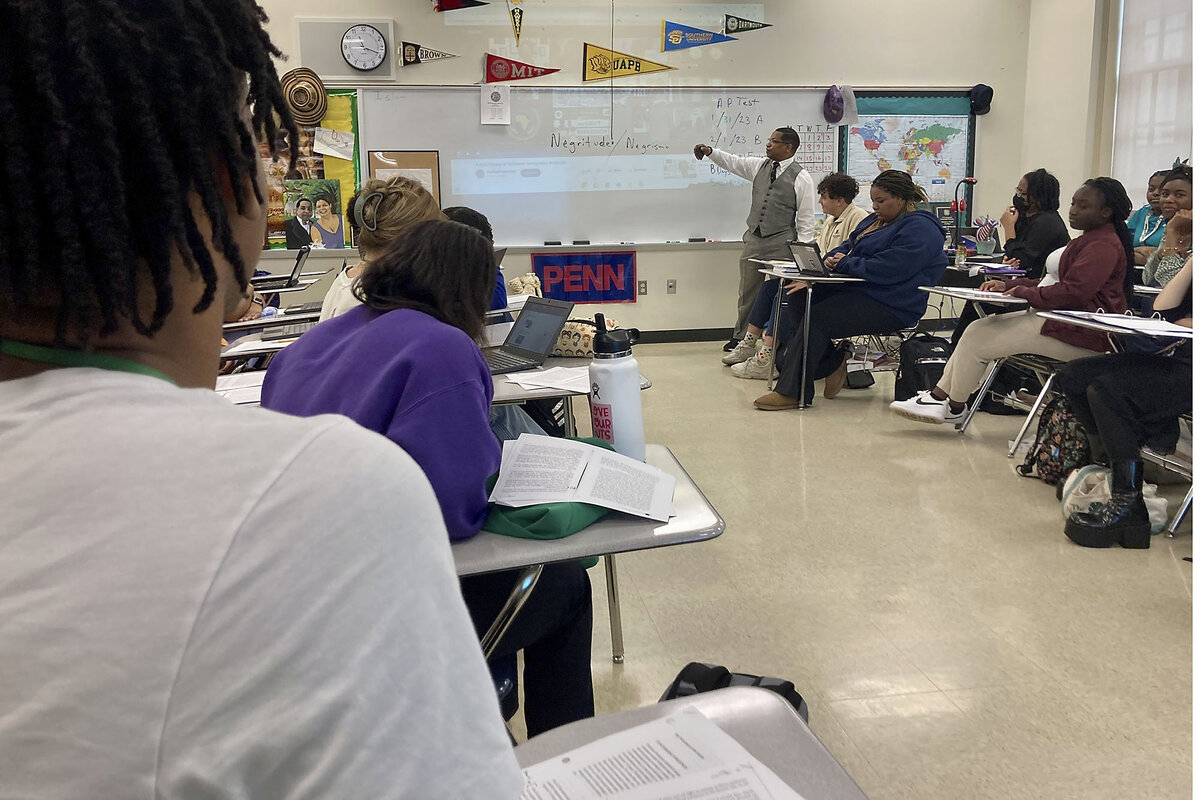

I had a chance to speak with Dr. Scott by phone recently. Like Black History Month, he is a Chicago native deeply rooted in the study of a people. A retired Howard University professor who is now teaching at Morgan State University, he grew up in the Windy City during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. He says he’s been writing about Black history since “second grade.” And even that barely scratches the surface.

In grammar school, he studied history at the George Cleveland Hall library branch. “That library was named after one of the [ASALH] founders. One of the librarians there was Vivian Harsh, who was a life member of the association and a contemporary of Carter G. Woodson,” he says. “So I had this kind of genealogy that runs alongside the history of the association.”

Dr. Scott’s life is a reminder of the timelessness of Black history. Wherever one chooses to pick it up is the start of something important, and at the same time, part of a larger and more beautiful narrative. The ASALH birthed Negro History Week, inspiring a wave of Black history clubs and general interest. The period of cultural revival stemming from the civil rights struggle of the 1960s transforms Negro History Week into Negro History Month, and ultimately, the current high-profile presentation.

During our conversation, I briefly revisit my old thinking about Black History Month and its relevance. Dr. Scott says something sobering in response: “Let’s be careful, because we could be too glib about that.”

“[Woodson] may have desired for Black history to always be included in all aspects of American history when it comes to K-12. ... but that does not preclude having Negro History Week,” he says. “The concept of Negro History Week was that what we learned all year about Black people, we would talk about and give special focus in February. ... He understood that things are always talked about in particulars, so you don’t lose particularism if you tell the larger story.”

The study of Black history isn’t only an exercise in specifics, but irony. For as much as Black History Month has become a commercial endeavor, it is still an appreciation of Black people, founded by Black people. And its origins in trying to incorporate Black history into overall history fly in the face of opponents who see the commemoration as racially divisive.

But the depths of that irony go beyond the superficial, and are a challenge around how Americans appreciate history overall, explains Dr. Scott.

“One of the most fascinating things that people don’t know is that February was American History Month before it was Black History Month. American History Month used to get all the presidential proclamations where Black history, Negro history, we got none,” Dr. Scott says. “And yet, Negro History Week becomes Black History Month by the mid-’70s, and everyone has forgotten that February was American History Month. So the only history that has taken root successfully as a kind of public celebration of history is Black history.”

Perhaps it’s fitting that ASALH’s 2025 theme for Black History Month is African Americans and labor. Remembering the past and carving out space for the future require work.