Why ‘equal opportunity for all’ and DEI are not the same thing

Loading...

The early days of this political administration have shown the dangers of a homogenized understanding of civil rights. There is an alarming amount of people who don’t understand the difference between diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives and the link between equal employment opportunity (EEO) policy and justice for all.

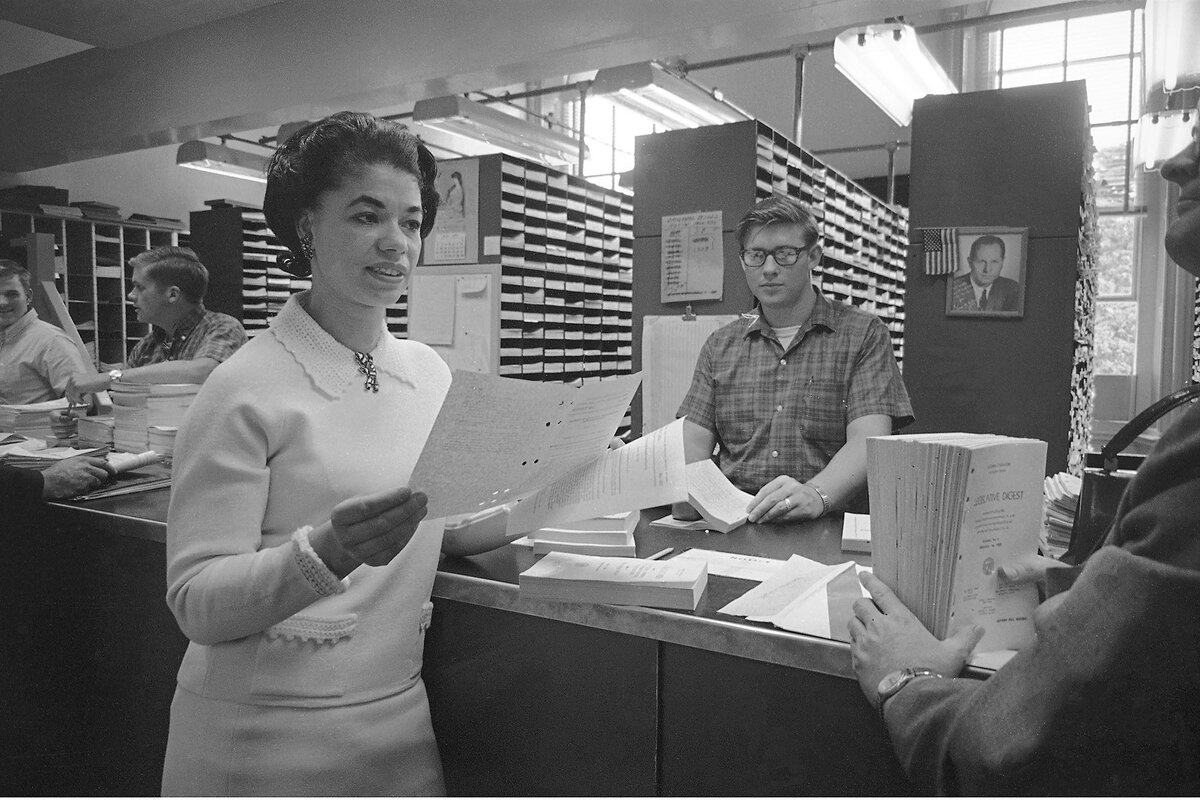

When the White House posted the executive order “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity” on Jan. 21, it took aim at DEI in the name of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This was particularly ironic. Further, it notably revoked the Equal Employment Opportunity rule of 1965, which then-President Lyndon B. Johnson used to close a loophole relating to government contractors. The EEO’s antidiscrimination origins began in federal employment. It has since been used as a standard-bearer across virtually all organizations, whether private, state, labor, education, and so on.

Political opponents of DEI and equal opportunity efforts have presented them in a way that suggests they will only be beneficial to African Americans, which in and of itself invites and incites racism. Certainly, initiatives that help Black people are viable because of the ongoing legacy of systemic racism. With that said, civil rights legislation, not trickle-down economics, has truly been the “rising tide that lifts all boats.” Such policy has sought to eliminate not only racial inequity, but has made room for women, veterans, those who are disabled, and LGBTQ+ people.

Why We Wrote This

How often have we placed our hands over our hearts and declared, “with liberty and justice for all”? Quite simply, the 1965 Equal Employment Opportunity rule the president revoked his first week is quintessentially American, our columnist writes.

A modest flyer at a storage location jogged my memory. It’s a flyer one might see at most places of business. “Equal Employment Opportunity Is The Law,” read the header, with “The Law” in bold, black letters. I first learned of EEO policy during my city beat in my native Augusta, Georgia. I watched two Black female department directors encounter their own episodes of discrimination, while at the same time fighting for fairness for others. Much like the irony of using civil rights legislation to revoke DEI, watching Black women face attacks for doing due diligence in the equal rights space didn’t escape me.

One of those directors was Jacqueline Humphrey, who led EEO for the city for six years until she was fired in 2015. She later filed a federal complaint, alleging that she was the victim of workplace discrimination. In her suit, she argued that she was demoted and then terminated after she investigated a complaint against another director. She and the city reached a settlement. I reached out to Ms. Humphrey to get her perspective on EEO.

“[People] don’t understand the constitutional rights behind what EEO stands for and what it means,” she says by phone. “Organizations do not want employees to have insight about their rights, because then they would have to solidify being fair in how they distribute money, positions, and contracts.”

The other director was Yvonne Gentry, who led the city’s Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program. A 2009 disparity study references the origins of the 1995 program, and the 1994 investigation that predated it. The program was created in the aftermath of “compelling evidence of a large disparity between the utilization of minority and women vendors and their availability in the Richmond County market area, much of which was attributable to the past and present effects of discrimination.”

Disparity, of course, speaks to differences in treatment and opportunities. When reached by phone, Ms. Gentry explains how programs designed to help the disenfranchised offer roadmaps for folks who have rarely or never engaged with government from a business perspective.

“A lot of times, people just don’t know where to go,” Ms. Gentry says. “That was the objective of the program, not making sure minorities get [preferential treatment].”

She adds that the Trump administration’s attacks on DEI seem targeted toward nonwhites.

“Diversity is such a wide brush. It can mean Black, Asian, disabled, a lot of things,” she says. “He’s not going after [unqualified] whites. He’s going after minorities.”

While there are countless champions to preserve equal rights, the modern-day work of civil rights can be traced back to one man: Martin Luther King Jr. It was tough to watch Donald Trump sign off on anti-DEI executive orders on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and the day after, because, quite simply, Dr. King gave his life for civil rights legislation.

History tends to speak in flowery terms about Dr. King and then-President Johnson’s relationship regarding civil rights. The truth is a lot less romantic. The two largely worked under tension and in secret because of the looming presence of Jim Crow. Further, the FBI sought to intimidate Dr. King, and President Johnson did not intervene. Nevertheless, profound policy came out of their high-risk collaboration.

This, among other reasons, is why criticism of DEI requires more nuance. There are entities who say it is unfair, despite the legacy of Jim Crow and the need for merit-based hiring. But there are others who contend that DEI doesn’t specifically target people of color, and in some cases, perpetuates whiteness.

There are ways to make DEI more equitable without eliminating it. Further, the consolidation of civil rights terms in popular language has led to the type of cultural misunderstanding that has put bedrock legislation at risk.

DEI describes a post-Black Lives Matter campaign that sought fairness among an educated class, which is certainly relevant. But this latest attack is an example of how anti-DEI rhetoric can be employed to harm standard-bearing legislation.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, of course, is still the law of the land. And private and government employees are still protected from discrimination. But here’s a chief section to remind us of the importance of the EEO rule of 1965: “It is the policy of the Government of the United States to provide equal opportunity in Federal employment for all qualified persons, to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and to promote the full realization of equal employment opportunity through a positive, continuing program in each executive department and agency. The policy of equal opportunity applies to every aspect of Federal employment policy and practice.”

How often have we placed our hands over our hearts and declared, “with liberty and justice for all”? Quite simply, this act is quintessentially American.