In US capital, rats thrive where civic trust is low. Here’s how to fix that.

Loading...

| Washington

Nancy Balph talks like a national security official about battling her enemy: More eyes, more boots on the ground. If you see something, say something.

She’s tracking a cunning adversary that can penetrate fortresslike buildings. It multiplies exponentially if left unchecked. It has been the bane of humanity’s existence going back to at least the Middle Ages.

It is the rat.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the age-old battle against rats, veterans in Washington, D.C., are reaching consensus that victory is measured not in annihilation, but in changing human behavior by building community trust and cooperation.

But it has met its match in Ms. Balph, a senior construction project manager at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., where a pungent odor grew as students emptied out during the pandemic and the rats moved in. At first she was curious. Then she was mad, thinking, “Wow, we can’t fix this? I find that hard to believe.”

Ms. Balph walked the campus with an exterminator, city pest officials, and rat-tracking dogs. She learned to spot the burrows, the brown trails created by an oil the mammals secrete as they scuttle along – and the holes along the bottom of loading dock doors. But her real breakthrough came when she found Robert Corrigan, a rodentologist who got his start crawling through New York sewers.

“It’s not Joe Schmoe with his spray gun and traps,” says Ms. Balph, who persuaded the university to hire him. “This is someone who will help us understand what is going on.”

Last on to-do lists, first to weaken civic trust

And what is going on, say many involved in the battle, is arguably a failure of society, of democracy – a breakdown of civic trust and cooperation.

Rats “are a sign of the erosion or decline of a public realm,” says former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, who in 1999 held what was reportedly America’s first Rat Summit.

Rats have long reigned in the capital of the most powerful nation – right under the nose of officialdom. At the U.S. Capitol, janitors and police testify – off the record – to their presence, with one claiming a bedraggled rat found on a bathroom floor came up through the plumbing. A big one scurried behind President Donald Trump during a 2020 Rose Garden appearance. Another sighting, decades before, caused the National Security Council to evacuate the Situation Room, according to a “top-secret” report obtained by The Washington Post. The newspaper also joked about rats exposing State Department divides over strategic weaponry: conventional broom and mop, or chemical agents.

The story of rats versus humans is age-old. But 300 years after the Enlightenment began, most of humanity is still battling these 1-to-2-pound whiskered creatures with poison or the brute force of Neanderthals.

Even Washington, which boasts three of the four most-educated ZIP codes in the United States and a federal government with a $6 trillion budget, faces an uphill battle. Last fall, Orkin pest control ranked it the fourth-rattiest city in America – after the much larger metropolises of Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York.

In July 1967, President Lyndon Johnson – addressing inner-city blight – sought $20 million for urban rat extermination. Though initially stymied by Congress, he got a rat control bill by year’s end. But it didn’t last.

“The federal government should, absolutely, have a national rat mitigation plan. And we don’t,” says Dr. Corrigan, noting that responsibility gets pushed to local governments, which generally aren’t strict enough about trash management. “It’s the last thing on everybody’s to-do list.”

Rats once owned this alley

The key to solving rat issues in any city is to change behavior – but not that of the rats.

“Rats need three things ... food, water, and a place to live,” says Gerard Brown, the district’s rat czar for 20 years. “And most of the time, we provide that for them.”

Last year, his Department of Health team of 17 inspectors got more than 17,000 calls. On a recent rainy morning, four of them walk with local residents between a row of restaurants and homes.

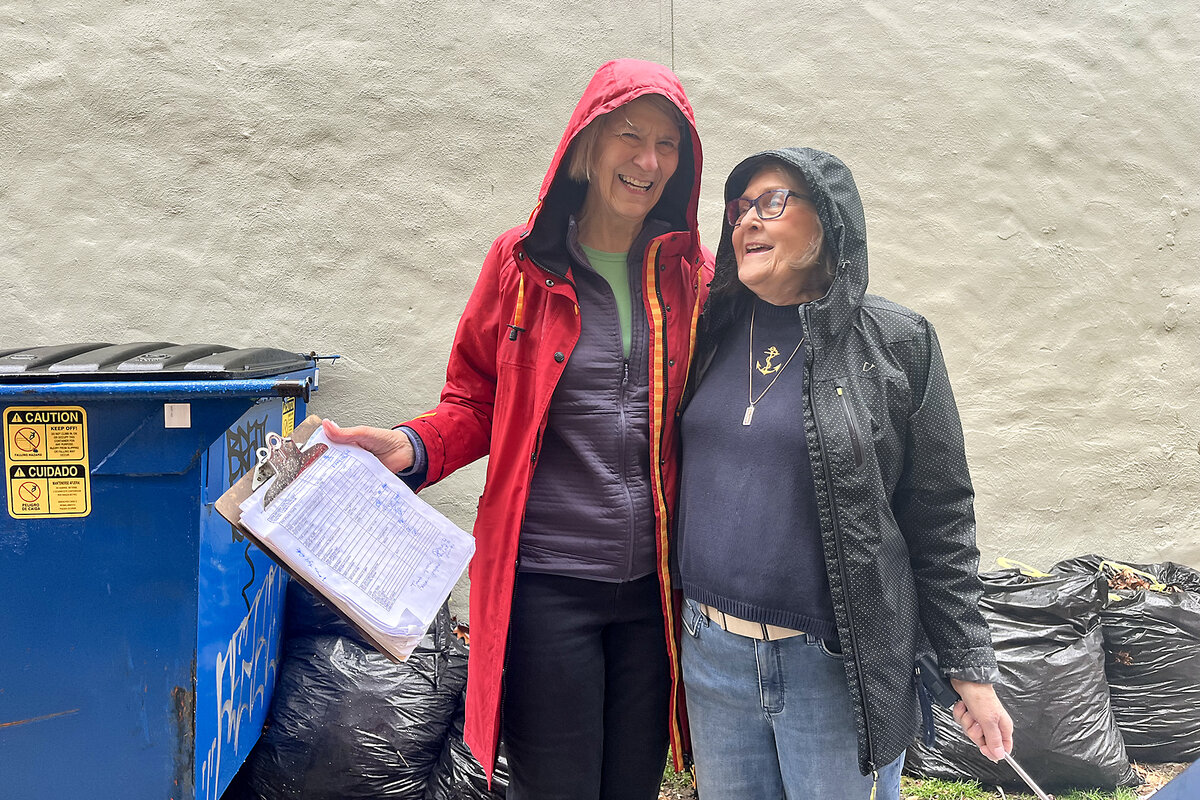

Seven years ago, “the rats owned this alley,” says Susan Sedgewick, a self-proclaimed “rat warrior” carrying a clipboard with a soggy stack of papers. Each line has a name, address, and space where she fills in the number of burrows found.

Flipping back to the middle of the stack, she points to improvement: “Back in April 2023, they had 12,” she says. “Now they have seven.”

Partly, that’s because she has hounded restaurants about controlling their trash.

It’s also thanks to fellow residents like Marian Connolly realizing they could do better. “I was in la-la land,” says Ms. Connolly, who would happily fill her bird feeder to attract songbirds. “It took me a long time to realize I was feeding rats.”

Jermaine Matthews, a Washington rodent control supervisor, says he loves working with the two women, both retired federal employees: “This is the greatest relationship we have, with these young ladies right here.”

The group of them has been taking these biweekly rat patrols for years, modeling the vigilance required to keep rats in check.

Then one of them spots something under the edge of a dumpster: a dead rat.

“It’s a baby,” one says, as Ms. Connolly averts her gaze.

It takes a unique character to deal with what Mike Rector of Eagle Pest Services calls “the new rage in pest control.”

“I’ve seen a lot of men very squeamish when a rat comes at them from a corner,” says Mr. Rector, who has seen a spike in rodent calls since the pandemic began.

On paper, two adult rats can produce 15,000 offspring a year, though that doesn’t actually happen, says Dr. Corrigan. A consultant to the district government for two decades, he praises Mr. Brown as “absolutely outstanding.” But he adds that while officials are important to conduct inspections and collect data, in his experience, “those community groups can do more to get rid of rats in their neighborhood than the whole city working on it.”

A failure of the golden rule

Other residents, however, would like to see the city take a more strategic, engaged approach. Mary Mason has taken the lead on the lower portion of her block in the district’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood and often calls in reinforcements from the city. They are prompt to schedule an appointment, and the inspectors sound like they know what they’re talking about. Then she gets a notice: Your request is closed.

But inevitably, she finds herself calling again. To her, it’s symptomatic of a local government that isn’t as responsive, let alone proactive, as it should be when it comes to “regular life for regular people who live here” – particularly in less well-to-do areas of the city.

Former Mayor Williams says many children are bitten by rats, and the problem is worse where residents live in substandard housing and are preoccupied with more pressing challenges than trash containment.

The Shaw neighborhood used to be like that when Brian Bakke moved in two decades ago and picked up a broom as an act of care for his neighbors. He still sweeps daily, covering several full blocks with garbage bags stuffed in his back pocket. Most days, he finds a few dead rats too, and sends “headshots” to the city to persuade them to take measures like replacing “rat plates” that keep rodents out of trash cans.

He tries to spread the gospel of rat-free living, encouraging other residents to join him in calling the city and engaging with neighborhood children, who like playing with the pretend rat skeleton in his yard. “You talk to the kids, and the kids will change the parents,” he says.

A man of faith, he says the issue is symptomatic of a failure to love one’s neighbor as oneself: “I see this as a microcosm of what is ailing our nation today.”

Not eradication, but effective management

Big neighbors like George Washington University can also make a real difference for an urban neighborhood.

When Ms. Balph got in touch with Dr. Corrigan, he came to GW, walked the campus, and produced an 80-page report. Rats, he says, need to be respected as an “incredible” mammal and scientifically managed, like wolves. “We haven’t put the science into managing rats – we’ve only put poisons into managing rats,” says the Purdue Ph.D. In many cities, he adds, codes require buildings to be rodent-proof, but the professional building industry could do more to ensure that openings under doors and around pipes and wires are properly sealed.

Following Dr. Corrigan’s recommendations, Ms. Balph led a team in “the rat battles.”

They ordered Kevlar door seals and excavated 4 feet of earth from landscaped gardens to lay rat-proof geomesh. They’ve just finished installing impenetrable Bigbelly trash cans on every street corner and even considered birth control, but Dr. Corrigan dissuaded them.

The university spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to implement his recommendations. Every dollar was worth it, says Ms. Balph, who considers the efforts 100% successful.

“Did we eradicate rats from the GW campus? No,” says Ms. Balph, who still texts Dr. Corrigan at every hour of the day and night. “We are managing them very well though.”