At Women’s World Cup, a growing focus on fairness in pay

Loading...

The Women’s World Cup 2023 is underway in Australia and New Zealand, and it’s smashing television viewership and ticket sales records.

FIFA, the organizer of the World Cup, says fans have already bought nearly 1.7 million tickets to the games, and corporate sponsorship is surging. More eyes are focused on the biggest event in women’s soccer than ever.

But fans and observers are again asking why the world’s best women players should be awarded so little compared with those on the men’s teams.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe FIFA Women’s World Cup is setting records for viewership and ticket sales. Yet as our charts show, women players lag far behind men in pay, a gap that some nations are trying to address.

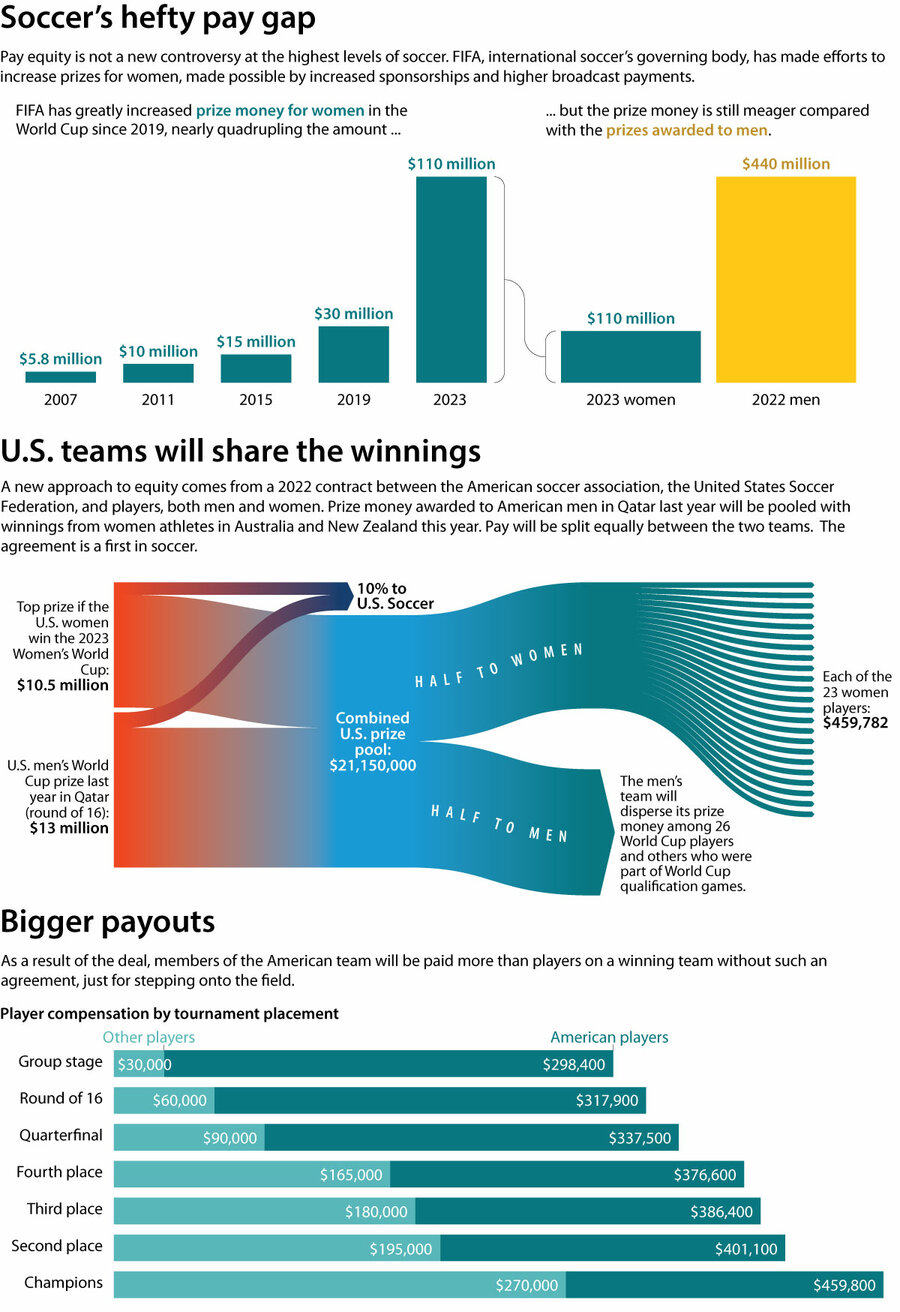

This year’s prize pool totals $110 million, a giant increase from $30 million in 2019 but a far cry from the men’s 2022 World Cup trove of $440 million.

Unhappy with this imbalance, American players from both the men’s team and world champion women’s team reached a deal last year with the United States Soccer Federation, the sport’s national governing body, that makes compensation for athletes fairer. Under the new deal, men and women will pool their winnings and split them 50-50.

FIFA pays prize money to each country’s soccer association, not directly to players. Many countries’ associations pay players per the terms of negotiated labor contracts. But about two-thirds of teams do not have such contracts, leaving their soccer associations to disburse prize money as they see fit. Athletes have complained about late and missed payments, and unfair compensation. The average salary for Women’s World Cup players worldwide in 2022 was $14,000. Earlier this year, FIFA promised to ensure each woman in the tournament was paid at least $30,000 but admitted in June that it could not guarantee national associations would distribute the money in that way.

Some national federations, such as those in Australia and Japan, have made their own collective bargaining agreements intended to improve pay for women athletes, and others, such as Denmark’s, offer player bonuses. But the majority of players in this year’s tournament will not benefit from such agreements and are subject to FIFA’s pay structure.

FIFA says it will aim for pay parity for the 2026 and 2027 men’s and women’s World Cups. Until then, deals like this may be the best way to ensure that prizes for the top tournament are distributed equitably.