‘Real journalism.’ Inside the battle to save local newspapers.

Loading...

| Brunswick, Ga.

There was something about the item on the police blotter that puzzled Larry Hobbs, a former farmhand and store clerk turned local newspaper reporter.

A young Black man out for a jog had been shot and killed in a quiet subdivision on a Sunday afternoon. The police went quiet. There were no arrests.

“Something didn’t add up,” says Mr. Hobbs, who speaks in a country drawl and wears his blond hair long. “The question just hung out there: Why?”

Why We Wrote This

Local newspapers have long been integral to how communities see themselves, so their financial struggles represent a public crisis that is beginning to elicit a political response.

The killing of Ahmaud Arbery and the county’s hesitation to arrest the three white men allegedly involved led to local and national protests and, eventually, to the arrest of the suspects. And, for some at least, it put the spotlight on the importance of a low-key stalwart of democracy: the local newspaper reporter.

The murder “didn’t paint the community in a good light,” says Mr. Hobbs. “But we also covered how the community redeemed itself with loud, angry protests that left all the cars sitting on four tires. We showed the world how change works. We didn’t flinch. That’s why what happens in local news is real journalism.”

None of that means Mr. Hobbs will have a job going forward at the six-days-a-week Brunswick News. Like many other local newspapers, it’s struggling to stay afloat as revenues decline and readers drift away.

The U.S. has lost roughly 2,400 newspapers in the last 15 years, about a quarter of the total. Fat city broadsheets now offer slender pickings, infilled with newswire copy. The pandemic only accelerated the trend, with over 30,000 jobs lost, many permanently, in the last year. Even as TV and digital media jobs have grown, print positions have been halved in the past two decades.

Laid-off beat reporters aren’t the only victims. So, too, is civic trust in local and national news as building blocks of democracy. And the crisis in a once-thriving private industry has become a public crisis that, some say, necessitates a political response, though what form that should take is contested. Nobody thinks Washington is about to bail out local newspapers whose business model has imploded. But they might give them a helping hand.

“There was a sort of happy accident that newspapers took on an important civic function in the 20th century, and for a while many of them could afford to pay for that. But now they can’t,” says Columbia Journalism School dean emeritus Nicholas Lemann. “So, what do we do to preserve that civic function? We’re finally having that discussion.”

Blank pages, hard times

Last month, the Kansas City Northeast News framed the issue in graphic form by publishing a possible future: a blank front page. The drastic move generated publicity and donations, and the weekly newspaper has since resumed its community coverage.

Chances of massive relief for the newspaper industry are slim. But hundreds of lawmakers have raised concerns about the issue, indicating that there is support for helping the industry, according to a University of North Carolina report on local “news deserts.”

In Congress, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell is a co-sponsor on a bill that would allow newspapers to join forces in order to negotiate more favorable deals with digital platforms like Google. For his part, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has thrown his support behind a bill that would allow family-owned community newspapers to restructure how they fund their pension commitments.

There is also movement to lift IRS restrictions to make it easier for newspapers to convert to nonprofit status while still selling advertising.

And there has been concrete action as well. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting received an extra $20 million on top of a $75 million stimulus supplement last year; some of that money went to support local broadcast reporters. Some are urging Congress to include local newspapers in future funding.

Even before the pandemic, New Jersey lawmakers had set up a modest fund to subsidize local newspaper operations.

The momentum is a recognition that “when you lose a local newspaper, you’re losing the person who covers the school board and town council,” says Penelope Muse Abernathy, a visiting journalism professor at Northwestern University who studies the economics of digital media and news deserts. “In other words, you’re losing the reporter who is going to tell you how you share the same problems and possibilities with your neighbor.”

Behind this debate is a sobering fact: The newspaper biz has shed jobs at the same rate as the coal industry.

The mining analogy is apt. Local papers, after all, provide the raw ore of information that filters up to regional and national media organizations. Taking them away leaves a news void that is filled by social media that is overwhelmingly driven by national trends. Attempts by companies like Facebook to provide local channels are hampered by a lack of content and timeliness. Last year, one such feed in North Carolina posted a story about preparations for a hurricane that had crossed the area days before.

“An increased reliance on national news sources causes people to lose touch with their community, especially as national news has become highly partisan and more manipulative than informative. That’s something that happens as a result of this vacuum,” says Duke University professor Philip Napoli, author of “Social Media and Public Interest: Media Regulation in the Disinformation Age.”

At the same time, many Americans seem unaware – or perhaps don’t care. A 2018 Pew survey of 35,000 people found that over half mentioned they had seen less local news, but most weren’t aware that their local newspapers were in danger of going out of business.

A short goodbye

Sometimes a newspaper dies quietly, its readers long gone. Other times it ends with tragedy.

Waycross, Georgia, a prosperous old railroad town, lies an hour west of Brunswick, not far from the Okefenokee Swamp. In 2019, the Waycross Journal-Herald, its newsroom shrunk from 15 to 4 reporters, shut down. Not long after, the paper’s publisher, whose grandfather had acquired the paper in 1916, walked into his office and took his own life.

Only minutes before, Rick Head, the paper’s sports editor who was preparing to relaunch the title as a weekly, had said goodbye to his old boss.

“I think it all just got to him when he walked into that office where his dad and granddad had run the paper for so long,” says Mr. Head, who now runs the Journal-Herald from a new office around the corner.

“A lot of people felt sad that the paper closed,” says resident Barbara King, a former reader. “That’s how we kept track of what was going on, including obituaries.”

But a younger resident, Shannon Fleming, says the city of 13,000 didn’t generate enough news to justify a daily paper. Now, he relies on lawyers and city officials who drop by his clothing store for news from city hall. “The fact is, I’m not willing to pay for local news,” he says.

Sitting in a plain office with only a box of crackers on a shelf, Mr. Head says he understands the road ahead will be difficult. Some locals don’t even know the weekly paper exists. Mr. Head is used to multitasking: He recently had bylines on 35 stories and briefs in one edition. “I often pass myself on the road,” he says, barely joking.

Show me the money

Such stories point to the biggest problem: money. Pew found that between 2008 and 2018, advertising revenues fell by 62% in the newspaper industry. Google and Facebook now gobble up 77% of revenues in local ad markets.

But the growth of news deserts can also be attributed to aggressive cost-cutting by large newspaper chains that control more than half of all papers. Job cuts leave the remaining reporters trying to do more with less, and readership continues to shrink.

That charge is leveled at Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund that is trying to take full control of Tribune Publishing Co., which owns the Chicago Tribune, The Baltimore Sun, and a string of other newspapers. Last week, a rival $680 million offer was made for the titles by two wealthy individuals, raising hopes that reinvestment could stave off the cycle of cutbacks and declines.

Analysts say not all newspapers are likely to find a rich benefactor, so they made need other ways to survive, whether from government support or nonprofit ownership. But the clock is ticking.

“We’re not adjusting fast enough to rethink local journalism as a public good, which brings so much fundamental benefit to democracy and society,” says Viktorya Vilk, director of digital safety and free expression programs at PEN America, a national nonprofit that champions writers. While the crisis has led to innovation, it hasn’t replaced the financing that has been lost, she adds. “We have incredible ideas and outlets. But there’s not enough money in the system to feed them and keep them going.”

A promise of local bylines

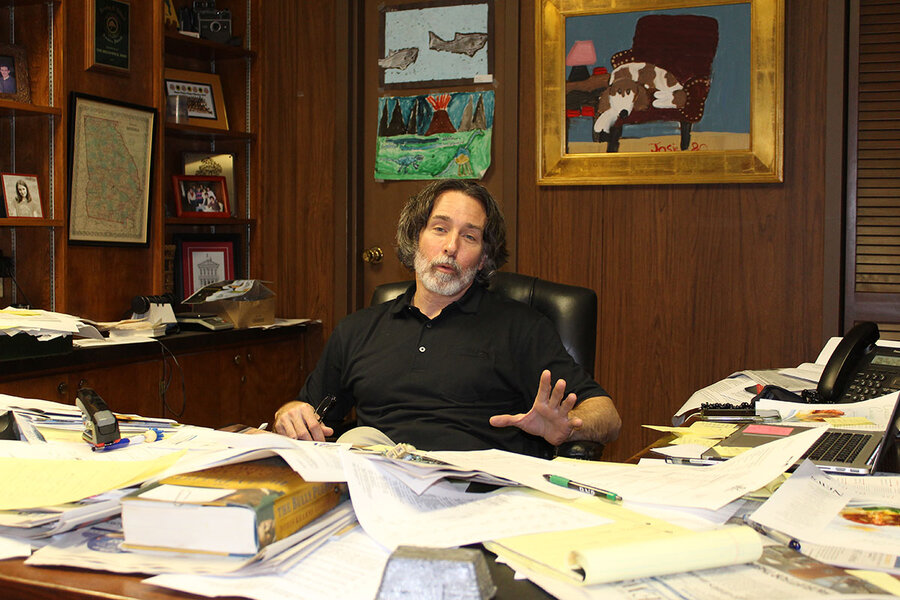

Buff Leavy is the middle-aged publisher of the family-owned Brunswick News, covering a town of 16,000. He is the fourth owner in his family, and he knows that he may be the last.

He’s keeping an eye on possible relief from Washington, including efforts to reduce the burden of turning papers into nonprofits while still selling ads, he says.

But for now, his main mission is to remind readers of why the news is not just informative, but critical. He will soon begin running a “pledge banner” that promises at least 10 local bylines per day, and he says going hard on local news is already bringing in more digital subscribers.

“We are increasingly acknowledging the fact that local newspapers are, in fact, important to democracy,” he says. “I think our readers are, too.”

He is being helped by the efforts of Mr. Hobbs, who covered two big national stories this year: The Arbery murder and the salvage of the Golden Ray, a ship that capsized in St. Simons Sound in late 2019 with thousands of cars aboard.

Mr. Hobbs writes several columns on top of his daily story load, including a lighthearted look at local misdemeanors, names withheld. He lets creativity fly. “A jerk went berserk,” he recently wrote.

More serious crimes, of course, get harder coverage. He recently interviewed Mr. Arbery’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, for an anniversary story about her son’s shooting. The three men charged with his murder are set to go on trial later this year.

As the interview wound down, Ms. Cooper-Jones smiled at Mr. Hobbs and told him, “Thank God for the Brunswick News.” And then she said, in a quote that didn’t make the paper: “And thank God for you.”