Books before borders: Letter from a library on the US-Canada boundary

Loading...

| Derby Line, Vt.

Kathy Converse wanted to do something productive after life as an English teacher, so she decided to volunteer at her local library. A straightforward path – not prone to bumps or wild curves.

Or so she thought, she tells me one recent day at the bustling Haskell Free Library. Instead her workplace sits – quite literally – atop the US-Canada border. As such it bears witness to heartache and joy, fear and suspicion, and one time even gun smuggling.

“There’s nowhere in the world like this,” she says.

Why We Wrote This

An institution like the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which sits on top of the U.S.-Canada border, relies on warm international relations. What happens when temperatures across the border turn chilly?

The Haskell Free Library and Opera House, which was deliberately built to span the international boundary in 1904, is a symbol of cross-cultural cooperation and has fascinated visitors for over a century. It’s a place where the border at Stanstead, Quebec, and Derby Line, Vermont, is delineated with a thick piece of black duct tape that runs through the reading room, and where the theater’s stage sits in Canada and most of the seats in the U.S.

It’s perhaps even more enthralling today, at a time when national walls are in vogue. And even the U.S.-Canada border, long heralded as the longest friendly border between two countries in the world – marked outside the library with a row of potted plants – has become more fraught.

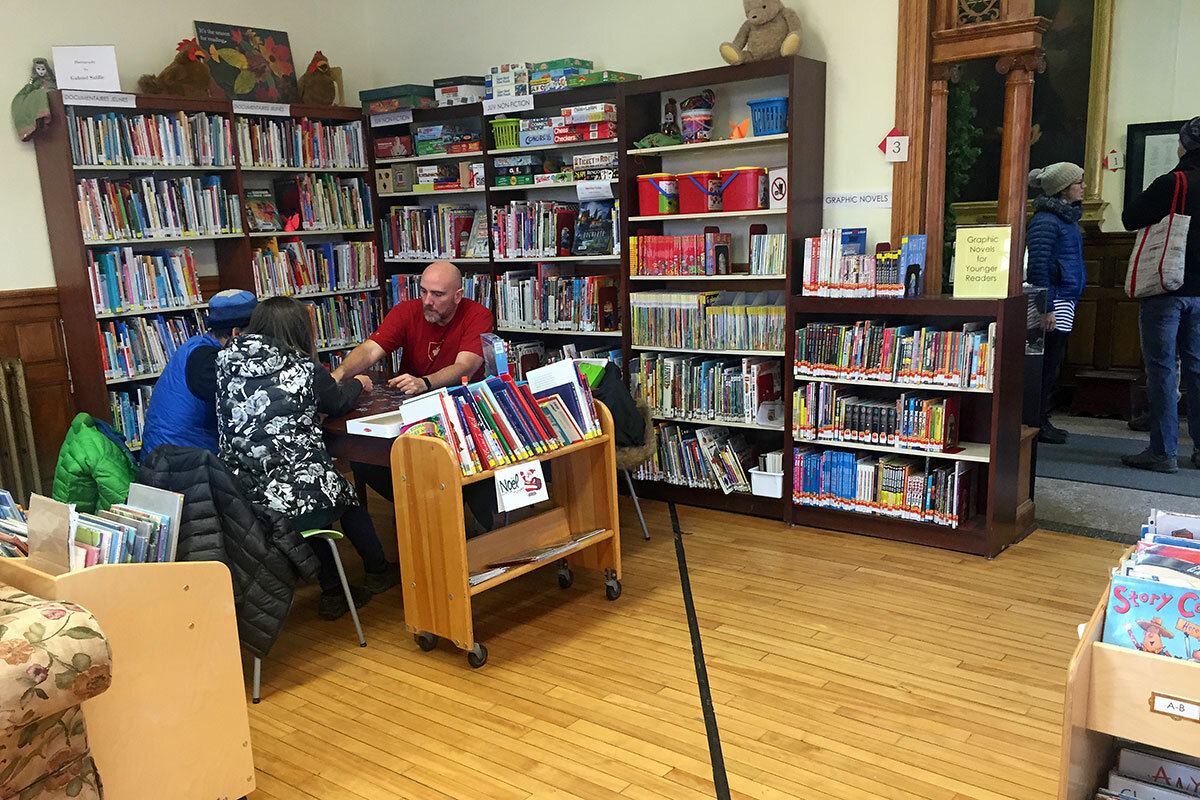

On a recent day, U.S. border officials roam the streets of small-town Vermont, watching for comings-and-goings through the library doors. But inside, borders seem irrelevant and random. As I returned from interviewing locals, I found my 9-year-old reading in Canada, while the adults who were supposed to be watching her were doing a puzzle in the U.S.

Pretty shoddy babysitting, I joked.

People from all over the world come here – from as far away as South Korea, and as close as Montpelier and Montreal. They take photos straddling the border tape with arms spread, a Canadian flag in one hand, an American one in the other.

Laila Lima, who lives near Montreal, was visiting with her family. “I felt like crying,” she said, after hearing a story recounted by Ms. Converse. The library volunteer spoke of a grandmother and grandchild who met for the first time inside the walls, one of many foreign families split by tougher immigration policies in the U.S., but who find neutral territory in the Haskell. Visitors from Canada can follow the sidewalk across the border and freely enter the library’s doors – they just can’t go anywhere else. Visitors from the U.S. cannot walk too far down that same sidewalk or they could be detained.

It was not always this strict. Scott Wheeler, a local historian who publishes the Northland Journal, recalls growing up with a border that felt more like somebody else’s imagination.

“We knew Stanstead and the Derby Line were in two different countries, but you didn’t really think about it as such,” he says. On Saturday nights, when there were hockey games in Quebec, all you had to say was “hockey” at the border. “And they’d wave you on.”

That of course all changed after 9/11. Mr. Wheeler has become an unofficial guide for visitors in this region, and he always finds their perspective illustrative. Europeans accustomed to passport-free travel across their continent are dismayed by the restrictions now in place. The South Koreans, he says, are amazed that two countries are separated with flowers.

As for locals, some have refused to adapt. Instead, they avoid the border altogether. “I think a lot of it is our fierce stubbornness, that we don’t want things to change,” he says.

If most residents are resigned to a new post-9/11 normal, in some ways the library faces more challenges today. Irregular border crossings have spiked northbound, as the U.S. under President Donald Trump has placed more restrictions on immigrants and refugees. More than 16,000 were stopped crossing into Canada by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 2019.

It plays out in the library when family or friends can’t get permission to see each other any other way, which then brings heightened attention from the border establishment. “The best word would be ‘challenge,’” Ms. Converse explains of the effort to keep their heads down. “Our job is to serve our patrons.”

That job is harder here than in most libraries, says local Peter Carragher. And that’s not just because it’s a bilingual collection and clientele. In 2018, a man was sentenced for smuggling guns into Canada, at one point via a stash in the trash bin of the library bathroom.

“There’s people who come by casing the joint. They have to be ready for them and not reveal too much,” says Mr. Carragher, who lives on the Quebec side but comes daily to Jane’s Cafe in Derby Line, where he and his wife leave their own mugs that bear their names. “It puts them on the spot, and they’re not qualified or trained for that. That’s not their function as a library.”

As I head out of the library with my daughter, husband, sister, and brother-in-law, we are stopped by a border patrol officer. He asks for our passports because another officer notified him we may have illegally passed into Canada. That’s cause for arrest, he explains. He’s kind about it as he lets us go, but it’s disconcerting.

It did give me a glimpse of life on a tighter border – and a deeper appreciation for that sanctuary within the library’s walls.