Bridging black and white: How St. Louis residents are trying to surmount racial inequities post-Ferguson

Loading...

| St. Louis and Webster Groves, Mo.

Elyssa Sullivan never expected to get thrown in jail. The white suburban mother lives in a tony enclave on the outskirts of St. Louis with street names like Joy and Glen, a world apart from the turmoil that erupted 16 miles away in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014.

She had no inclination to join the protests sparked by a white policeman’s fatal shooting of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old, that overnight triggered a fraught – and painfully familiar – national debate on race relations in the United States.

“I was really scared,” says Ms. Sullivan. “I kind of bought that narrative, ‘Oh, that city is on fire; look at those protesters. I care about what they’re saying, but that’s not my place.’ ”

She never thought that three years later she would count a former battle rapper among her personal role models, or that she would scrawl “White Moms for Black Lives” on poster board and march down a highway. She couldn’t imagine that a police officer would yell obscenities at her – and another would zip-tie her wrists together.

But there came a point when Sullivan concluded that it was more dangerous for her to sit at home, ignoring what she now sees as an unequal justice system for black and white people, than to drive her minivan downtown and stand face to face with police in riot gear. Even if it meant spending a night in jail, as she ended up doing, unable to get an answer about the charge against her and denied a phone call to her husband and two kids.

“It just made me hyperaware of how no one is listening when people of color in our community have shared their stories of how they’ve been brutalized by police and damaged by police,” she says.

Sullivan is part of a broad movement that has sprung out of Ferguson, in which white people are increasingly joining a spirited crusade by black people to foster racial equity in St. Louis. They see the Midwestern city as a modern Selma, Ala., fueling a new civil rights movement. From schools to homes, from courts to churches, they are combating the city’s long history of segregation and racism – and building on the often-forgotten pioneers of civil rights in Missouri.

While St. Louis still lags behind many other cities in instituting police and criminal justice reforms, Ferguson has acted as a catalyst for change, from more grass-roots political engagement to the departure of a much-criticized police chief. Perhaps more important, it has led to a more frank dialogue between black and white people that could provide a path forward for a country cleaved by racial division.

“If we can be as successful in St. Louis as Dr. King and the civil rights leaders were in Selma, it could change this country as Selma did,” says the Rev. Darryl Gray, who participated in the original civil rights movement and has been a major force behind the drive here.

In the immediate aftermath of the Ferguson shooting, activists sensed the mood was right here and across the country for a major new push forward on social reforms.

But the election of Donald Trump and the emboldening of the white supremacist movement, combined with few convictions in police shooting cases around the country, dashed many of their hopes. Then, a few months ago, a St. Louis judge acquitted Jason Stockley, a white ex-police officer, in the shooting death of African-American Anthony Lamar Smith in 2011.

Mr. Stockley had pursued Mr. Smith, who was on parole for possession of marijuana and an illegal firearm, after witnessing a suspected drug deal. When the car chase ended in a crash, Stockley approached Smith’s vehicle and shot him, later testifying that he saw a gun in the suspect’s hands.

Heroin and a gun were found in the car, and an FBI investigation ended without prosecution of Stockley, a West Point graduate and Iraq War veteran. But after the officer had left the force in 2013, and the department had paid a $900,000 settlement to the Smith family, fresh evidence surfaced showing that the gun in Smith’s car bore only Stockley’s DNA. The prosecution argued it had been planted by the officer.

Stockley’s acquittal in the face of the new information stunned many who had worked for systemic change post-Ferguson, and it ignited a fresh round of protests.

Yet this time something was different. More than half the faces were white. That was intentional, taking a page out of the Selma playbook, says Mr. Gray.

In 1965, after state troopers brutally thwarted a march from Selma to Montgomery, Martin Luther King Jr. put out a call for whites to join them. Marching as a united front against voter discrimination, they reached Montgomery and helped persuade President Lyndon Johnson to enact the Voting Rights Act.

Adopting that strategy in St. Louis, black and white people have been protesting together amid trendy cafes and fancy suburban malls, challenging the idea that racial inequity is only a worry in neighborhoods with broken windows and empty streets.

Not everyone is happy with the new activism.

Some conservative whites believe it is misguided. They see rallying around black victims with suspected or demonstrated criminal backgrounds, questioning court verdicts, paying large settlements to families of police-shooting victims despite investigations clearing the officers, and forcing police officers to move away from the city as undermining law and order.

Yet the new social movement extends far beyond street protests. It involves a broad range of initiatives – many of them involving people of all colors working together – springing up everywhere from preschools to Pottery Barn-furnished living rooms.

Tiffany Robertson watched her neighborhood turn toxic after a police shooting, this one of VonDerrit Meyers Jr., a young black man, in 2014.

“There was so much polarization in the community ... I didn’t want to choose a side,” says Ms. Robertson, who is African-American. “I didn’t want my children to choose a side.”

So she started Touchy Topics Tuesday and invited white people to ask tough questions. She posed one of her own: “What about my skin offends you?”

The group has evolved to include a diverse mix of people, from airline pilots to police officers. Participant Sarah Riss has started another branch, in Webster Groves, where Sullivan lives, and she also runs the Alliance for Interracial Dignity, a group that promotes racial equity.

Other bridge-building efforts have focused on children. Laura Horwitz and Adelaide Lancaster, two white mothers, have started We Stories, which helps parents spark conversations about race and racism through children’s books. In two years, more than 550 families in 67 different ZIP Codes have been through their program. Several hundred more are on a waiting list.

City Garden Montessori was spearheaded by two mothers – one white, one black – who wanted a school with kids from a rich mix of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. The school, which gets two applicants for every available slot, has become a model of integrated education and an avenue for improving cross-racial understanding and cooperation.

“It was a bit of an experiment to see if we are all coming together around our children and engaging in each other’s lives in ways that we would not be otherwise,” says executive director Christie Huck. “Can we begin to break down barriers and build meaningful relationships across race and class and strive to interrupt racism and these patterns that keep our region stuck?”

Witnessing Whiteness, a group inspired by a book of the same name, holds workshops to help people “notice and respond to interpersonal, institutional and cultural racism.” Sisters CARE – Christians Advocating Racial Equality – brings together a diverse range of Christian women to foster understanding. Other parent groups are pushing for more equity in schools.

“The old PTO guard is scratching their heads, like, ‘Why is there so much juice around this racial equity conversation?’ And they are figuring out how to support it,” says Farrell Carfield of Webster Groves, noting that her Parent Teacher Organization enthusiastically contributed funding.

“St. Louis certainly has the potential for being a model for creating ... important systemic change,” says Adia Harvey Wingfield, a sociology professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “But only if the conversations that are happening now are coupled with actual attempts to address the institutional processes that maintain racial and gender inequality.”

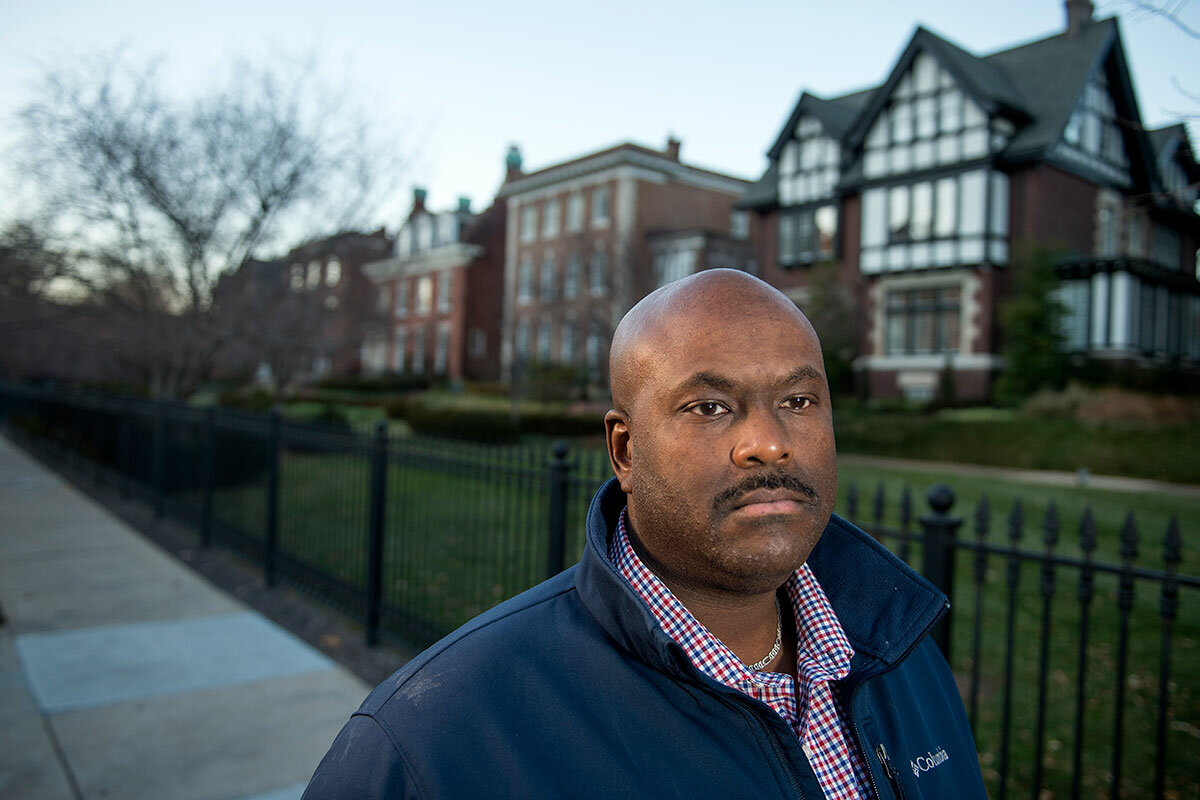

The solution to St. Louis’s problems may lie as much in how those of the same race deal with each other as in cross-racial work. Consider the experience of police Sgt. Charles Lowe. On a sultry night in July 2015, he was moonlighting as a private security guard when an intuition told him to put his bulletproof vest back on.

The African-American officer was still wearing his police uniform after getting off his shift at 2 a.m. He had done a walk around the property, then gotten back into his car, taken off his vest, and turned up the air conditioning. The impulse was insistent: “Put the vest on.”

Lowe, who says he felt a divine presence, heeded the directive. He also became aware of two young black men nearby. Soon a third arrived. They must be waiting for an early morning bus, he told himself. Then they disappeared.

Suddenly, a Ford pulled up. A guy got out, gun in hand. Lowe caught a glimpse of those inside. He was sure it was the men he’d seen moments ago.

The gunman fired at him through the front windshield. Lowe shot back, feeling midway through emptying his weapon that he’d been hit on his side. But, in fact, the bullet had lodged in his vest. While immensely grateful to be alive, Lowe has a question for his fellow African-Americans.

“I’m black, I got shot, and I’m a policeman fighting every day to make this community safe. Doesn’t my life matter?” asks the 15-year police veteran. “Or was it because I was wearing a blue uniform that it doesn’t matter?”

The Brown shooting unleashed a wave of African-American fury toward white police officers, who continue to be heavily criticized. But African-American officers such as Lowe are not exempt from such scrutiny. Within their own communities, they face distrust and even outright hostility.

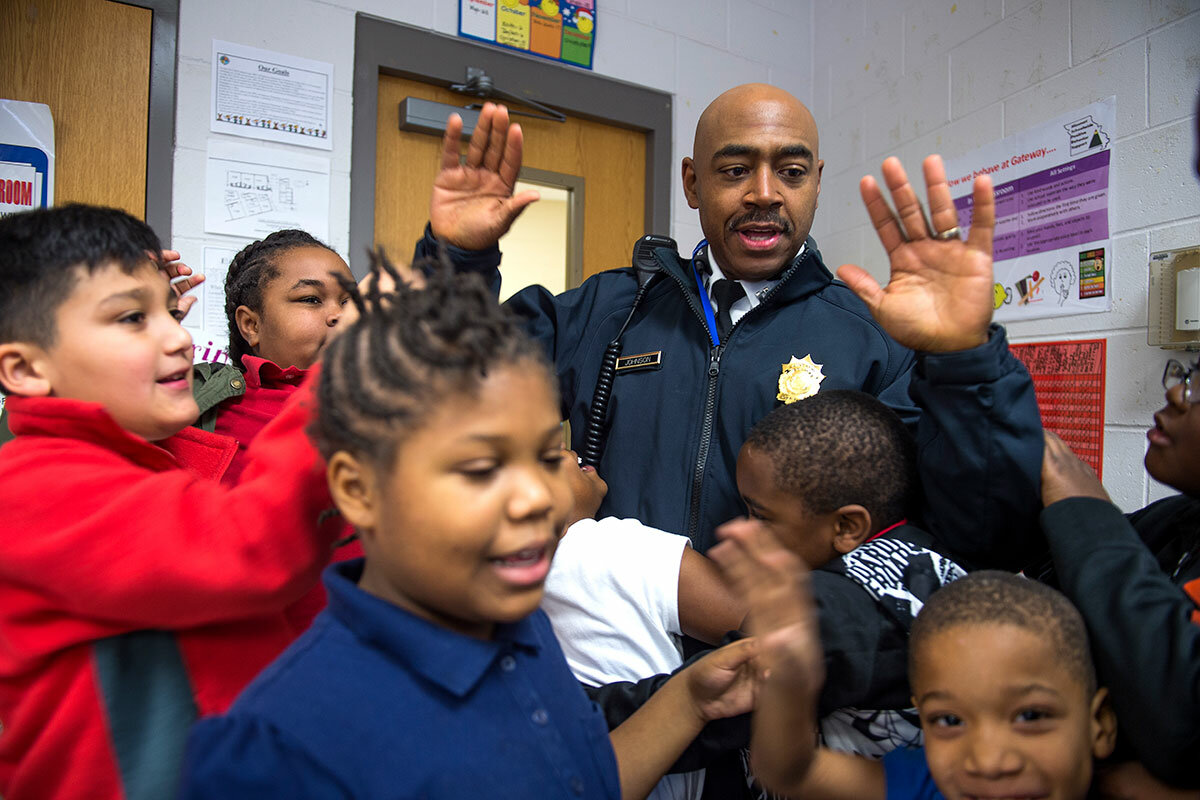

Perri Johnson, who is an African-American police captain and participant in Touchy Topics Tuesday, is now planning to start a similar group to promote understanding between black officers and black residents.

He was struck by an African-American adult who confessed to him that he was afraid of law enforcement. The 2015 Ferguson Commission report, which examined the root causes of the Brown shooting and subsequent protests, cited research that showed a big gap in trust of police – only 37 percent of black Americans trust officers versus 59 percent of white Americans.

“I had someone come to me and say, ‘Well, you know what, as a black officer, you need to quit your job [as a form of protest] and turn your badge in,’ ” says Mr. Johnson. “Well, that doesn’t make any sense.... There are a lot of people within the department that want to make change.”

Johnson, who is deputy commander of the police department’s Bureau of Community Outreach, says 90 percent of people in the black and white communities are good. The same goes for police officers. “We have to help each other with our 10 percents,” says Johnson.

The officer is also helping to break down stereotypes within the department, teaching required classes on racial profiling. Though blacks make up 47 percent of the population in St. Louis, they account for only 29 percent of the police force today – and the disparity grows starker in the higher echelons of the force. The Ethical Society of Police, the city’s black police union, found in a 2016 report that among many of the most prestigious units, 80 to 100 percent of officers were white. While expressing support for the majority of officers, the report described systemic biases along racial lines.

“As with any organization, we can always do better,” says Ed Clark, president of the St. Louis Police Officers Association, the main police union. “We want everyone to feel like you got a fair shot at promotion, or a special job, or even getting hired.” But he adds that no one has ever come to him and said they believed they hadn’t gotten a job because they were a minority – though some white officers have told him they got passed over in favor of less-qualified African-Americans.

Often overlooked in the racially charged conversation about policing is the increasingly dangerous environment in which the city’s police force operates. Since 2011, incidents of murder and non-negligent manslaughter have risen 66 percent in the city, according to FBI statistics. And that affects officers – white and black – not only as cops but as residents.

“We are part of the community,” says Mr. Clark, who – like many officers – lives within city limits. “We don’t want to worry about our families when we’re at work.... We want the crime to go down. That’s what I think everyone is working for.”

St. Louis has a mixed legacy when it comes to racial issues. Missouri entered the Union as a slave state, and it rejected Dred Scott’s quest to win his freedom through the courts. As recently as 1948, Missouri’s highest tribunal upheld a lawsuit that banned a black family from occupying a home in a white St. Louis neighborhood – a decision later overturned by the US Supreme Court.

Yet civil rights activists in Missouri were also among the first to push for the desegregation of buses, lunch counters, and other public places. Despite these pioneering efforts, however, St. Louis today ranks as the fifth-most-segregated city in the nation.

“Often we want to, and a lot of white people want to, jump to healing without really reckoning with the history and the mistrust and the deep hurt,” says David Dwight, a member of Forward Through Ferguson, a group created to implement the 189 recommendations of the Ferguson Commission. “And you have to deal with that first, before you can get to healing.”

An 18-year gap in life expectancy exists between blacks and whites in neighborhoods here just 10 miles apart. Close to six times as many black children live in poverty in St. Louis County as white children. The state headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan lies just an hour’s drive from the city.

In the wake of Ferguson, a US Department of Justice investigation revealed that the largely white city government was deriving millions of dollars in revenue from mainly poor, black citizens stopped for minor traffic violations. Because of their inability to pay the initial fine, many of those ticketed spent weeks or months moving in and out of jails, navigating court appearances, and shelling out fees, fines, and bail payments.

It’s a pattern that lawyers say remains common – and deleterious – across St. Louis County. “We’re not getting public safety by fining or jailing or citing folks whose contact with the legal system is a result of their poverty,” says Thomas Harvey, executive director of the legal advocacy group ArchCity Defenders.

Yet many changes have taken place in the city since 2014. In April, Lyda Krewson became St. Louis’s first female mayor. She appointed an African-American judge as her director of public safety, which oversees the police department. She has also pulled together a citizen advisory committee to help find a new police chief.

In November 2016, Kim Gardner became the first African-American to be elected circuit attorney, the office that prosecutes state-level criminal cases in St. Louis, on the promise of trying to restore trust in the criminal justice system.

One of her top concerns is how to investigate police shootings. Currently, a Force Investigation Unit within the police department takes the lead on such inquiries. But after Stockley’s acquittal, Ms. Gardner asked the city’s Board of Aldermen for $1.3 million to create a unit that would become the lead investigative body. She argued that her office had not been able to access key interviews and obtain relevant documents – a charge the FIU disputed.

“At what time do we think that a body who is investigating one of [its] own is appropriate?” asks Gardner. “It deteriorates the public trust.”

Other changes have come from the courts. In November, a federal judge ordered the city to refrain from using chemical agents such as pepper spray and other tactics against people engaged in “expressive, nonviolent activity.”

Yet the police have their supporters, too. Just days before the judge’s ruling, the city voted overwhelmingly to pass Proposition P, which gave the police department more funding – a move Clark, of the main police union, says reflects confidence in the men and women in blue.

Ultimately, some residents believe the best way to improve race relations in the city isn’t through street protests but the ballot box. Dellena Jones, a hair salon owner in Ferguson who is still paying off loans for damage caused by the riots, holds classes on how to fight discrimination through government channels. “There’s other ways of doing things, like voting,” says Ms. Jones. “You can’t say the system is flawed if you don’t work the system.”

A few activists are going even further: They’re running for office themselves. One, former battle rapper Bruce Franks Jr., is now a state legislator. Cori Bush, a nurse and pastor who took her ministry to the streets of Ferguson, is vying for a seat in Congress in 2018. Ms. Bush decided to run after watching elected officials remain silent or visit the protests just for a photo op.

“There have to be people in positions of power that actually love the people, that have a heart for the people, and that the people actually love and respect as well,” she says.

But social change doesn’t come through legislative action alone. Some of it comes through private conversations and shifts in attitudes. Sullivan, the suburban mother, is using the post-Ferguson ferment as a teaching moment for her children. She’s also been talking with friends about what she’s learning – though it hasn’t always been well received.

When she shared on Facebook her account of being arrested during a demonstration, an account that was widely circulated, some people accused her of embellishing the story. And a few longtime friendships have flagged as Sullivan has taken to the streets to promote racial equality and push for fairer police practices.

Yet she seems committed to her new crusade to foster change, even if it means sacrificing nights at the gym and occasional reading time with her children. “I don’t think white people can place all of the burden of protest and speaking up and educating and changing hearts and minds and policy ... on the people who are being oppressed by our white racist systems,” she says, sitting at her dining room table. “That’s our work.”