'Thoughts and prayers': For devout, what does it mean to pray after tragedy?

Loading...

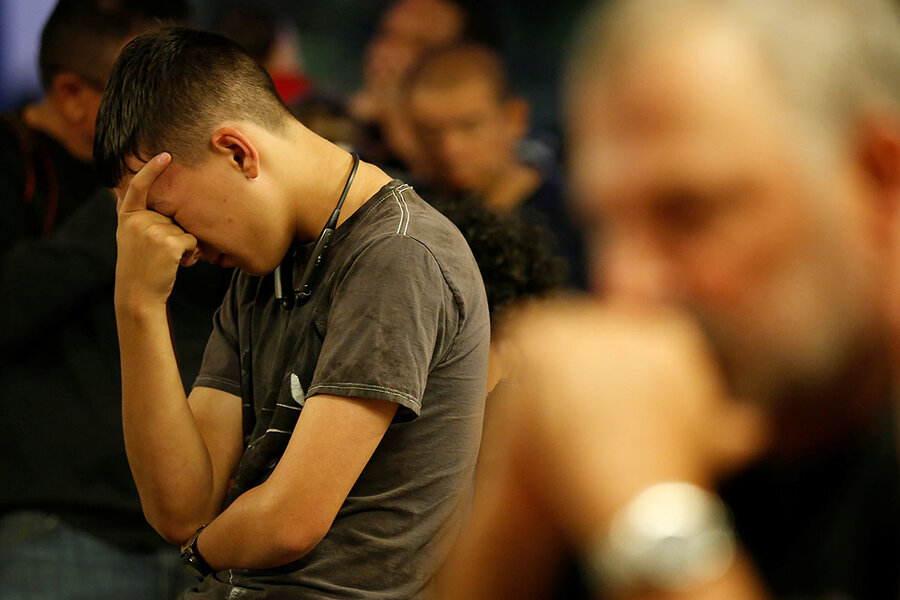

It’s a familiar performance in a long-running drama: Following a mass shooting, proponents and opponents of gun control take to the national stage, find their blocking on the scene, and recite the same impassioned lines of dialogue. But the circumstances of last week’s gun massacre in Sutherland Springs, Texas, flipped the usual script. When politicians doled out their automatic condolences of “thoughts and prayers,” gun control advocates responded with rhetorical jiu-jitsu.

“The murdered victims were in a church. If prayers did anything, they’d still be alive,” tweeted “Star Trek” actor Wil Wheaton, one of a number of Twittizens who used the cruel irony to mock Republican politicians. (He later apologized for offending “people of faith.”)

The recurring “thoughts and prayers” meme stokes fiery exchanges in a political and cultural war where gun control and religion are frontline issues. But after the shooting in Texas, the debate is no longer just about whether politicians’ stock platitudes represent a sufficient response to gun violence. It’s an argument over the very efficacy of prayer itself. Is God a refuge and strength, an everpresent help in times of trouble, as a Psalmist once put it?

“We are fundamentally spiritual beings,” says Richard Mouw, professor of faith and public life at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif. “It’s a part of our deep longings and hopes and fears that we do have a sense of the divine. In the moments of tragedy in our lives there’s an impulse, there’s an instinct to turn to however we understand the higher power.”

But beyond the individual supplications of the religious, there’s little agreement over the proper role of prayer after a tragedy. Does prayer constitute taking meaningful, practical action? Or does invoking “thoughts and prayers” merely offer the appearance of acting?

That cliché, plucked from the inadequate lexicon of words to express grief, is a phrase employed by countless Republicans and Democrats over decades (including politicians from both parties last week). Its durability may stem from the fact that it nods to both secular and religious audiences and also fits neatly into a sound bite or a tweet. But it has to come to represent, for some, a parsimonious response that fails to convey a full reckoning of the tragic loss of life in each incident.

In 2015, President Barack Obama responded to the mass shooting at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Ore., by declaring, “Thoughts and prayers are not enough.” Since then, the primarily Republican “Thoughts and Prayers” contingent have been satirized (and trolled) by an online videogame, an episode of the Netflix series “BoJack Horseman,” a gospel choir on Samantha Bee’s TV show “Full Frontal,” and an online comic by Stephen Byrne in which two superheroes, Thought and Prayer, discover that their respective powers are ineffectual against a robber with a gun.

Different faith traditions – and different people within those traditions – encompass a broad array of ideas on what prayer does.

“Is prayer enough to stop an individual from acquiring an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle and gunning down 50 people at a concert?” asks Rabbi Yael Ridberg of Congregation Dor Hadash, a Reconstructionist synagogue community in San Diego. “No. But that’s only if you think the prayer is supposed to solve that problem. That is not going to solve that problem. Prayer is a reaction to, or a need after the fact.”

For religious scholar Reza Aslan, the question isn’t: “Does prayer work?” Or, “Is prayer enough?” “Paul Ryan and most Republican politicians are saying, we will just hide behind the view that a majority of Americans have, which is a prayer is an effective tool and not do anything,” says Mr. Aslan, author of a new book, “God: A Human History.” “In a sense, we are inoculated from action, because most Americans do believe that prayer is a form of action.”

'Please keep praying for a solution'

Deliberation over the proper balance isn’t exclusive to the gun-control debate. During the 1980s, Dr. Mouw recalls attending an anti-apartheid meeting in Grand Rapids, Mich., in which a black South African church minister had been invited to speak.

“We talked about the [economic] divestments and church pressures and various things,” says Mouw, author of “Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World.” “At the end, she said, ‘Do all of these things but please keep praying for a solution to all of us in South Africa.’ A young African-American man stood up said, ‘I’m getting sick of praying. I want to do something.’ At that point she said, in a very stern voice, ‘Prayer is doing something. You’re petitioning the highest ruler in the universe.’”

People pray in a variety of ways. For some, it’s a simple call from the heart. For others, it’s the recitation of a complex liturgy. Prayer can be for oneself or it can be an act of intercession. It can be an act of petition or an act of praise. It can be silent or spoken aloud. Though the practice of supplication has been declining in recent decades, it nonetheless remains deeply woven into Americans’ lives – and thus their political outlooks.

“In our big 2014 religious landscape study, we found that 55 percent of all American adults said that they pray every day,” says Greg Smith, Associate Director of Research at the nonpartisan, nonprofit Pew Research Center. “Another one in five, 21 percent, say that they pray ‘occasionally,’ maybe on a weekly or monthly basis, but not every day. The remaining quarter or so of the public, 23 percent, say that they seldom or never pray.”

Another trend? More Americans now say they’re spiritual but not religious. Many people now gather for daily contemplation in yoga studios, not just to perfect flexible poses, but to deal with stressful events.

“What you meditate on can be breath, it can be counting, it could be a mantra, it can be connecting to your heart space and talking to God. It’s not only a Buddhist thing, prayer is absolutely meditation,” says Emily Peterson, lead trainer for a mindfulness-based trauma recovery program called TIMBo (Trauma Informed Mind Body) in Brookline, Mass. Ms. Peterson offers one additional definition of her practice. “The Dalai Lama, a while ago, was asked, ‘What’s the most important meditation one can do?’ He said, ‘Critical thinking, followed by action.’ ”

'When you pray, move your feet'

Theologian and author Leonard Sweet believes that prayer is a vital first step toward dealing with gun violence. “In a football game, your aim is to score a touchdown. But before you can score a touchdown, you huddle. But the game is not a huddle.”

Prayer is not an empty puff of air thrown up into the heavens, but something that takes flesh in some kind of materialization in real life, says Mr. Sweet, a professor at Drew Theological School at Drew University in Madison, N.J. “There is a wonderful African proverb: ‘When you pray, move your feet,’ ” says Sweet, who posts sermons at PreachtheStory.com. “If it is serious prayer and systemic prayer, it should move your feet to deal with systemic issues that are bringing this on.”

Republicans such as House Speaker Paul Ryan have been accused of dragging their feet on this issue. But other conservatives push back at the accusation that Republicans are acting in, well, bad faith.

“I absolutely believe the biblical concept that ‘faith without works is dead,’ ” says David French, a senior writer for National Review. “But what they tend to mean when they say, ‘You should pray and take action,’ is that they mean you should pray and take the action I want you to take. If you actually look at these politicians that they get angry at, or these conservatives on Twitter that they get angry at, each one of us has advocated or proposed or engaged in dialogue about various things that could be done to try to stop mass killings, to try to ameliorate the problem.” For example, he says, solutions could include stepping up enforcement of existing law – including increased prosecutions for those who lie on background check forms – and shoring up existing reporting processes so that names don’t fall through the cracks, as was the case in Sutherland Springs.

In the wake of the Las Vegas and Sutherland Springs shootings, Mr. French has been inspired by a verse in II Chronicles that stresses the importance of humbling oneself to listen for answers in how to deal with confounding acts of evil.

“[Christians] use a word that is fraught with very deep meaning, and that is ‘relationship,’ ” says French. “They feel that they have a relationship with God. That feeling of relationship with God is directly connected to prayer. It’s a feeling of communing with God. There is deep comfort. There is deep peace. There is resolve. There is insight.”

'Prayer, to me, gathers people together'

In Sutherland Springs, faith is at the forefront of a community that remains in a tight embrace since the Nov. 5 shooting that killed 26 churchgoers. At a prayer vigil last week, Pastor Stephen A. Curry, asked a candlelit throng, “Who are we going to be tomorrow? We are going to be people who go and live our lives, not in fear, but with compassion for our neighbors. Who are we going to be tomorrow? We are going to be people who do not let things like chaos and destruction interrupt who we are, or change who we are called to be.”

“Prayer, to me, gathers people together,” says Eileen Anderson, secretary of the Sutherland Springs Historical Museum. Before the shooting, Mrs. Anderson prayed daily for the world. Now, the Roman Catholic asks that world respond in kind.

“I couldn’t tell you how many calls I’ve had saying, ‘Eileen are you OK?’ ” she says, tearing up. “And I say, ‘Yeah, we’re fine. It’s the people down the road here that need us, need our prayers.’ ”

Staff writer Henry Gass contributed to this article from Sutherland Springs, Texas.