Luther’s legacy: How people use the Bible today, 500 years after a monk sparked the Protestant Reformation

Loading...

| CHATTANOOGA, TENN.

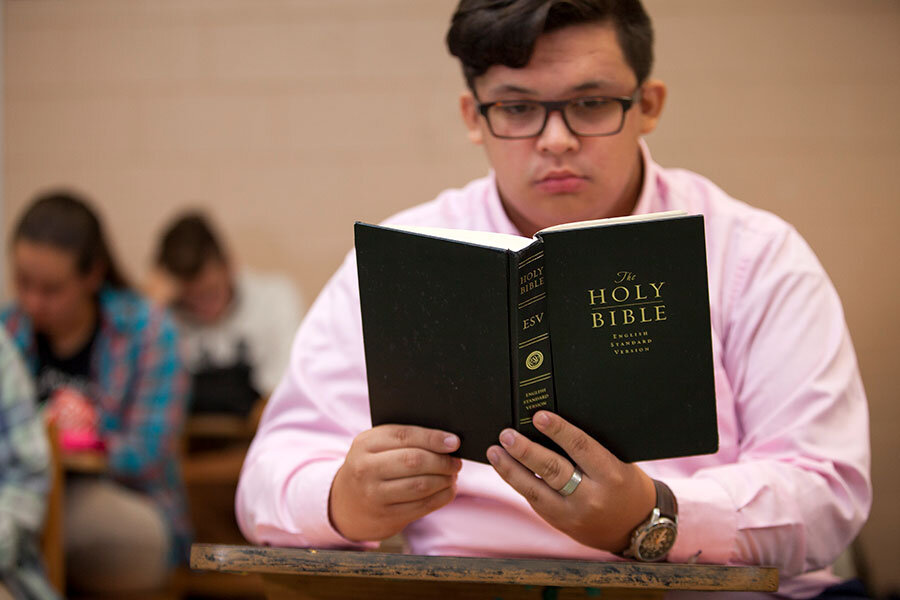

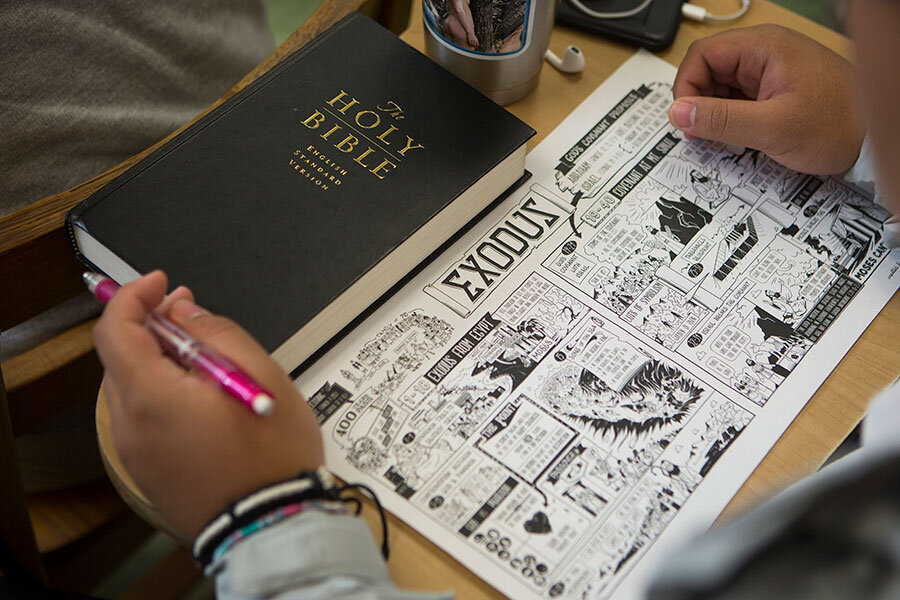

Students at Ooltewah High School in suburban Chattanooga are still yawning at their desks at 7:20 on a recent morning when teacher Daniel Ziegenmier says something designed to awaken their consciences.

“OK,” he announces, “time to put away your phones. Everyone come forward and get a Bible.”

Soon their minds are back in Old Testament times with help from a six-minute video summarizing Genesis. At Mr. Ziegenmier’s nudging, sophomore Jacob O’Daniel joins classmates in listing the good qualities of Abraham (blessed, clever), the bad ones of Lot (selfish, greedy), and reasons why keeping one’s word (such as God’s covenant with Abraham) is important.

For sophomore Jackson Clark, the material isn’t new. He’s already learned it in church. But he says he appreciates engaging with the Bible in a neutral setting, one with no religious agenda and no expectations about what to believe or how to interpret it. And he’s glad private donors give money ($1.3 million this year) to fund elective courses in Bible history for more than 3,700 of his fellow Hamilton County public school students.

“Even if you don’t have access to a church, it’s good to know about [the Bible] and be able to ... enjoy it,” Jackson says. “By taking this at school, they still get all the basic knowledge that you’d get out of church, all the stories and lessons that you get from reading the book.”

Bible courses are relatively rare in American public schools, where boards, including Hamilton County’s, try to avoid any whiff of religious endorsement or breach of the church-state divide. But here in the buckle of the Bible Belt, their growth is an example of efforts to foster reading the Bible – a practice that is a central legacy of the Protestant Reformation that was launched 500 years ago this month.

From Chattanooga to Johannesburg, in churches, schools, and living rooms, the reform movement fomented by an iconoclastic monk named Martin Luther has shaped how millions of people around the world seek God. Now, in the age of the internet, shifting cultural mores, and falling church attendance, the role of the Bible is evolving again.

In some Western countries, Bible use is in decline. In other regions, it is on the rise – and the internet promises to expand its reach even more. But how people actually interact with the Bible – whether they consider it the supreme authority on questions of faith, as Luther decreed it should be – is changing, too.

Perhaps nowhere are Luther’s legacy and the various ways the book is affecting everyday life more evident than here in Chattanooga, Tenn., the Appalachian city where public monuments quote Scripture and honor devout churchmen who helped make it the unofficial Bible capital of the world.

The man who rocked Christendom 500 years ago and made Bible reading a spiritual staple was among the least likely of revolutionaries. A miner’s son who harbored early ambitions to practice law, Luther turned to monastic life in a moment of panic: He promised during a violent thunderstorm to become a monk should God mercifully spare his life.

Luther fulfilled his vow, but Augustinian monkhood for him would soon involve much more than the usual prayer and fasting. His study of ancient biblical languages would open the floodgates of Protestantism.

At age 33, Luther hammered a fateful nail into the Roman Catholic Church – figuratively, and, according to popular legend, literally – when he posted his 95 Theses on the church door at Wittenberg Castle in Germany on Oct. 31, 1517. (Most scholars agree Luther’s theses were widely circulated, though probably not nailed to a door.) The pope’s selling of indulgences to those hoping to get deceased relatives out of purgatory had no biblical basis, Luther argued. He dismissed the practice of paying money to be absolved of sin as a corrupt, human invention rather than divine truth, even if the pope sanctioned it.

Luther’s core ideas – that humans reach salvation by grace through God-given faith, not their deeds, and that the Bible is the central religious authority – had been embraced by prior reformers. But the contentious, moon-faced monk crystallized them at a time when excesses and corruption made the Catholic Church susceptible to change.

As a result, the Protestant Reformation eventually swept the West, aided by new technology. The new printing press with movable type made publishing exponentially more efficient, starting with the Gutenberg Bible in the mid-15th century. Luther and others translated the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into local vernaculars.

“When the people could read the Bible for themselves ... in a language that they could understand, that’s what really caused the spiritual explosion of the Reformation,” says Jim Thompson, vice president of Bible League International, a Bible distribution organization based in Crete, Ill.

Since then, Protestants have been defined by the principle of sola scriptura, which holds that while other sources might deliver insights, the Bible is the supreme guide on questions of faith. And every human being should engage directly in what it has to say.

“At the end of the day, sola scriptura was the trump card,” says Thomas “Tal” Howard, professor of humanities at Valparaiso University in Indiana and co-editor of the book “Protestantism After 500 Years.”

“Christians reading the Bible on a daily basis – that didn’t really go on before the Reformation, or only to a limited extent,” notes Kathleen Crowther, a Reformation historian at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.

Today Protestants still embrace sola scriptura as an ideal. Forty-six percent of Protestants in the United States say the Bible provides all the religious guidance they need, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey. Another 52 percent say they also need guidance from church teachings and traditions, which is consistent with the early Reformers’ view as long as the Bible has the final say, says Mr. Howard.

But in practice, Americans are spending less time with the Bible and ascribing less authority to it than they used to. The percentage saying they read it at least weekly dropped from 46 percent in 2009 to 37 percent in 2017, according to the Barna Group, a Christian polling firm in Ventura, Calif.

“We have a growing biblical literacy problem in the US,” Mr. Thompson says.

Perceptions of biblical authority have been waning, too. Led by Millennials, 19 percent of Americans now view the Bible as “just another book” rather than an inspired text, up from 10 percent in 2011. The internet accounts for at least some of the Bible’s lost stature.

“What’s increased, especially with Millennials, is this questioning of authority in all places,” not just the Bible, says Roxanne Stone, Barna’s editor in chief. “It can be hard to have this sense of the Bible being an authority when you have a universe of knowledge at your fingertips.”

Overseas, proponents of direct Bible engagement face distinct challenges. In Europe, where the Reformation began, only 28 percent of the literate population owns a print version of at least one book of the Bible, according to data from the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Hamilton, Mass. Bible access ranks the highest in North America, at 95 percent, but it stands at only 16 percent in Asia and 29 percent worldwide.

One place where there isn’t a dearth of Bibles is Chattanooga. Here, in a city nestled between forested hills and a sweeping bend in the Tennessee River, 50 percent of the population reads the Bible at least weekly and strongly regards it as accurate in its principles, according to a 2017 Barna survey. As a result, the polling firm anointed Chattanooga America’s “most Bible-minded city,” which, given the book’s prevalence in North America, means it is probably the No. 1 city in the world for the holy book.

How that happened is a function of history and culture. Chattanooga is more traditional and pragmatic than it is flashy or trendy. Crafts are handed down to younger generations at places such as the Chattanooga Woodworking Academy. A manufacturing culture remains deeply embedded here: Workers on assembly lines bottle Coca-Cola, make cardboard food trays, and build Volkswagens, though the city also has an emerging high-tech scene. Signs point visitors to local history at every turn: Civil War battle markers, the infamous Trail of Tears, and the Chattanooga Choo Choo, a depot-turned-hotel and exhibit.

Faith and family run deep in this tradition-heavy culture. The area is home to dozens of churches, as well as many other major religious institutions, including five Christian colleges, Precept Ministries International, and the world headquarters of The Church of God (in nearby Cleveland, Tenn.).

“For a long time, [Chattanooga residents] weren’t into all the modernist stuff, high academic careers or being professionals,” says Ralph Hood, a psychology of religion professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. “They were more into being laborers and having simpler jobs that were conducive to their faith system.”

But even here, sustaining Luther’s vision of sola scriptura requires new creativity. This is evident on a Sunday morning at Chattanooga’s Trinity Lutheran Church. The first thing you see – after a cheery mural depicting Luther and his wife, Katharina – is a smorgasbord of Bible study groups.

In the church’s library, retired religion scholar Herb Burhenn unpacks John 16 verse by verse as a dozen seniors seated around a long table listen and nod deferentially. Down the hall, Mike Brandt leads a second group of adults in a more casual format. In a dining area, kids and adults cluster around small tables, where each offers an interpretation of Jesus’ teaching on reconciliation in Matthew 18.

Trinity offers multiple approaches to Bible study, according to the Rev. Stan Combs, because the path to experiencing the Bible’s authority varies so much in 2017 from one person to the next. That’s especially true in this era when countless experts and potential authorities – whether in religion, politics, or science – are always as close as the click of a mouse.

For some teens at Trinity, the Bible’s decrees are to be embraced no matter how much they go against popular culture. Fourteen-year-old Sam Sosebee, for one, believes his denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, needs to hew more closely to Scripture. “The Lutheran church lets gays be pastors, but that’s one thing I’m conflicted about because the Bible says you shouldn’t,” he says.

His 16-year-old sister, Abby, welcomes how the Bible challenges her group of friends to lead holy lives, such as by shunning the gossip that typically marks teenage social life. This fall, they’ve made the Bible their hardcore trainer for a spiritual fitness regimen that involves reading all 66 books in 90 days.

“It’s always been present in my life, but going and reading it myself has made it so much more real,” says Abby, still wearing her white vestments after reading the day’s Scriptures in worship. “It’s made me so much more passionate to just get it out there for other people to know about.”

Others at Trinity need interpretive latitude before they can buy in to scriptural authority. Anne Cain, a former Methodist, is learning to heed Scripture in a new way. She had been a licensed local pastor during college, but had to resign after making some “20-year-old mistakes,” she says. Now a facilitator of intergenerational Bible study at the church, she encourages everyone to remember that the book was written for particular people long ago and needs contextual interpretation.

“The way I use it now is different,” Ms. Cain says. “When I was younger, it was: ‘The Bible says this, this is the way it must be,’ without taking into consideration the historical context. But it was written by man, translated by man, had all this stuff done to it by man.... Now it gives me a guide.”

Embracing the authority of Scripture is getting more complex in African-American enclaves as well. Bible use is strong among African-Americans: 31 percent say they read the Bible more than four times a week, versus 19 percent for the general population, according to Barna research. And 49 percent regard the Bible as the actual Word of God, compared with 24 percent of all Americans.

But even in Bible-saturated Chattanooga, African-American Christians (like others) can be reluctant to let the Bible govern how they live their lives. That’s according to Rosalyn Hickman, a longtime Baptist who, together with her husband, Gary, does couples counseling for about two dozen congregations. They meet in the Hickmans’ living room, where an embroidered pillow captures the spirit: “Faith is all we need. That and some hugs.”

Some couples say they want to honor God, she says, but then insist on living together before marriage or maintaining separate bank accounts in marriage. Both are unbiblical practices, Ms. Hickman says.

“It’s harder now because I think people are more into themselves – smart, successful, and wanting to have it both ways,” she says. “They want to be considered Christian, but not according to Scripture.”

To help others warm to biblical authority, Hickman tells how the book has made a difference in her family. Her mother came to regret not living according to biblical directives and going out to clubs when she was single with young kids. Hickman took a different route. She came to faith at age 10 with help from white evangelists. By trusting in grace and pursuing biblical standards, she’s been blessed with a strong marriage, she says. Now she’s teaching a new generation of girls to dress modestly, for instance, and make time for daily Bible study.

Beyond Tennessee, the quest to encourage direct Bible engagement stretches across the globe as the Reformation enters its sixth century. It remains a hallmark of global Protestantism, which counts 800 million adherents after a surge of overseas mission activity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today, Protestantism’s center of gravity has shifted from Europe and North America to the Southern Hemisphere. A plurality of the Protestant faithful (295 million) lives in sub-Saharan Africa.

But those following in the Reformers’ footsteps abroad face distinct challenges to the sola scriptura method. Lack of access to the Bible remains a significant problem. Some 160 million people don’t have even one book of the Bible available in their language, according to Bob Creson, president of Wycliffe Bible Translators, a nonprofit based in Orlando, Fla. Technology, as in the 16th century, is helping. Translation software has cut the average time for translating the New Testament into a new language from 25 years to seven. By 2033, every person will be able to find at least one biblical book in his or her language, according to Mr. Creson.

Distribution remains a problem, too. Bibles often pile up in churches, never reaching people in remote locations. But believers are making inroads by using the Bible primarily as a tool for evangelism in countries such as Mexico, Ghana, Kenya, and the Philippines, according to Thompson of Bible League International.

Disseminating print versions remains important even in the Digital Age. That’s in part because more than half the world’s population still lacks internet access. Even where web usage is the norm, Bible readers prefer print versions by a large margin: 81 percent in the US opt for print over digital for Bible reading, according to Barna’s 2016 “The Bible in America” report.

Nevertheless, Bible distributors hope the web will soon usher in the highest level of Bible engagement in history. “Some people are calling digital the second Gutenberg,” says Thompson. “I think it one day will be.”

In Chattanooga, some view the Bible as a way to help improve morality among young people. The Bible in the Schools program is founded on the premise that Bible study “diminishes dishonesty, lying, profanity, and bullying” and otherwise improves moral character. (It avoids legal challenges over church-state separation by not promoting any religion, doctrine, or interpretation.)

“Education in general for the past 100 or more years has put all the emphasis on objective knowledge, so this is maybe the only exposure that they have to broad moral truth,” says Frank Brock, a board member of Bible in the Schools. “It can have immediate impact because [some students have] never heard anybody say, ‘stealing is wrong.’ ”

Still, studying the Bible has been no moral panacea for Chattanooga schools. In two reports on bullying over the past year, the Office of District Attorney General Neal Pinkston identified 122 incidents, called out a hazing culture on sports teams, and flagged “widespread, systemic problems going unaddressed at every level within Hamilton County’s public schools.”

But proponents of direct encounters with the Bible believe it can still have an edifying effect, even with all the countervailing forces in modern society. Some are convinced that the best way forward – for young and old alike – is to rely on traditional methods that worked in generations past.

“I still have the faith of a child,” says Eleonore Williams, a lifelong Chattanooga resident and member of Trinity Lutheran, who is 94. “A child is open to believe and accept.”

A retired accountant and avid hiker of the Great Smoky Mountains, Ms. Williams reads the Bible for 30 minutes daily after breakfast. In encouraging others to trust the holy book, she’s helped at least three people who were suicidal to find hope in God’s promises. “They have to read the Scriptures and believe them, not read them and be tearing them apart,” Williams says.

Even though busy lifestyles and numerous daily distractions keep many people from reading the Bible today, there are signs of growing interest in the Scriptures. A new Museum of the Bible will open in November in Washington, D.C. A children’s Bible museum, Trek Thru Truth, which will use interactive exhibits to tell 52 Bible stories, is planned for Cleveland, Tenn.

On this year’s 16th anniversary of the 9/11 terror attacks, about 300 people gathered at another site in Cleveland, the Peerless Road Church. Prayers focused on spiritually uplifting the mass media industry, which 33 percent of Americans blame for the nation’s moral decline. For 2-1/2 hours, singers, dancers, artists, and writers called for a national return to God – and the Bible.

“Take me to the place where a miracle is needed,” cried LaEsha Williams, a fiction writer from Rossville, Ga., before the arm-waving crowd. “Take me to the place of deepest darkness. Let me give light that was given to me.”

Luther, no doubt, would say, “Amen.”