How Cleveland has become a leader in trying to eradicate human trafficking

Loading...

| CLEVELAND

On a recent Friday night, when many women are spending time with their families or going to see a rom-com movie with friends, Renee Jones is doing something unconventional. She’s driving around Cleveland’s seedier neighborhoods, visiting some of this city’s most notorious strip clubs.

Her intention isn’t to see the young women perform. It is to connect with them in hopes of preventing the women from falling prey to one of the country’s most overlooked but vexing social problems: sex trafficking.

Around 8:30 p.m., in front of a small storefront on the city’s west side, she and three volunteers – including a nurse and a Roman Catholic nun – climb into Ms. Jones’s Mitsubishi Galant. At the first destination, the Lido Lounge, the women approach each dancer and hand her a gift bag. The packet contains a cornucopia of cosmetics, candies, and trinkets, along with a personal note.

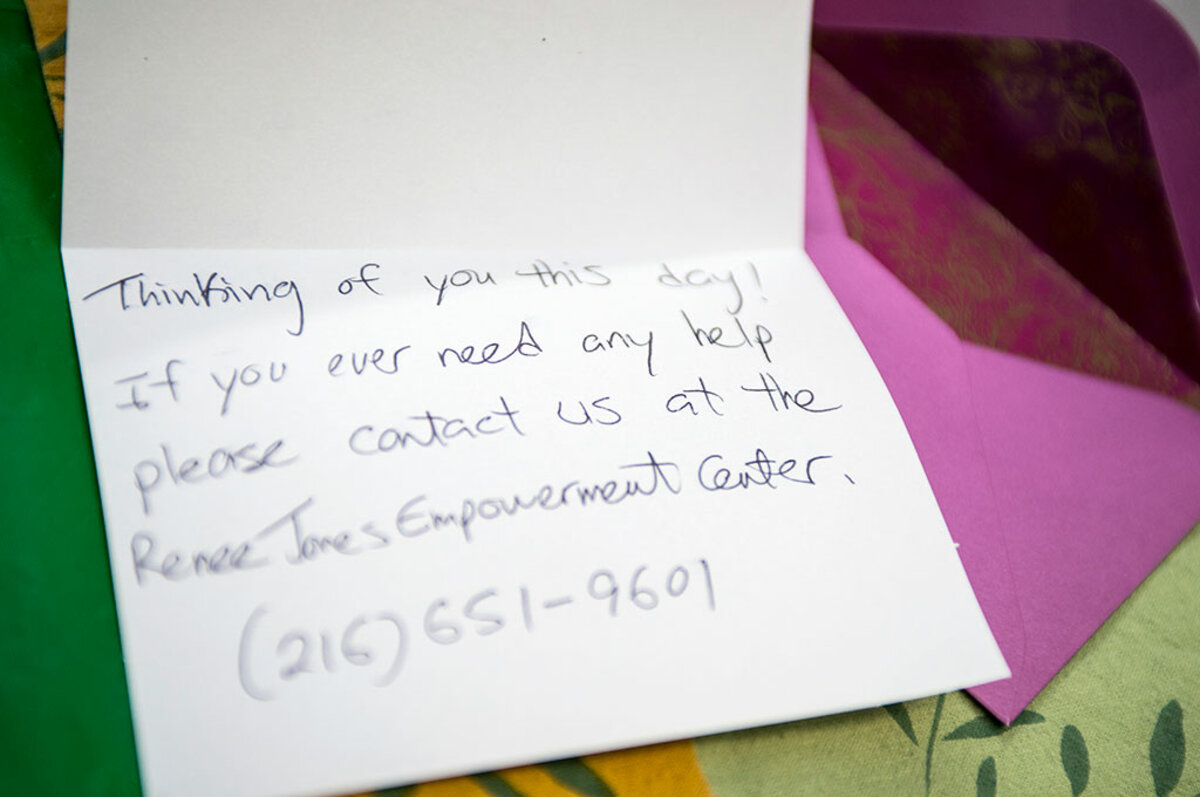

The note does not include any explicit instructions for the women to leave the strip club, or the owner wouldn’t allow them to distribute the bags. Instead, it contains a general message of support about their dignity and value. It is signed “Your friends from the Renee Jones Empowerment Center,” with the organization’s phone number.

The women get the subtext: If they are approached by anyone trying to coerce or compel them to work as prostitutes, they have a group they can turn to for help – and often do. The dancers gleefully rummage through the bags.

“I can’t explain what it is,” says Jones. “But I believe we have a grace to do certain things. These girls have a need, and we’re filling something that’s missing from their lives. [What we’re saying is] you’re a woman, and you’re worth it.”

Fearless and passionate, Jones is on a crusade to stamp out sex trafficking and provide women survivors with a place of comfort and safety. Her novel outreach effort is part of a broader campaign under way in Cleveland that is making the heartland city a leader in trying to eradicate a problem that affects thousands of young people each year.

The initiatives range from tougher laws against sex and labor trafficking, to special “safe harbor” courts that treat children caught up in prostitution more humanely, to a billboard campaign reminding Ohioans that all this “Happens Here Too.”

But behind all these efforts are a few individuals who are striving to chip away at a problem that many experts believe receives too little attention in society: people like Jones, a former corporate executive who used to work in the realm of pumps and pinstripe suits and now navigates an underworld of pimps, drugs, and fatal shootings.

“Renee is an angel, and I want her to be my mom,” says state Rep. Teresa Fedor (D) of Toledo, who has championed anti-trafficking bills in the Ohio legislature. “She’s incredible in what she’s built as a model for our nation.”

According to global estimates, sex and labor trafficking represent a criminal industry worth as much as $150 billion each year, second only to illegal narcotics. The dark enterprise victimizes nearly 21 million people, mainly women but also some men, and about 300,000 minors. Trafficking is believed to happen in every country in the world. Perhaps most disturbing, experts say that there are more sex and labor slaves in the world today than at any time in history.

Ohio is indicative of the problem. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center ranked Ohio fourth in 2016 in the volume of trafficking calls to its hotlines, after California, Texas, and Florida.

The state is susceptible to trafficking for several reasons. It has an extensive highway system that allows easy transport of victims, as well as a large number of truck stops that serve as active prostitution sites. Numerous strip clubs statewide provide fertile recruiting grounds for traffickers. Moreover, the current opioid epidemic that has hit the state hard – Ohio leads the nation in opioid overdoses – allows pimps to use people’s addictions as a way to coerce them into prostitution.

Jones does strip club outreach, for example, because she knows that traffickers recruit many women who work as dancers. Typically, the process starts with a pimp complimenting a dancer on her beauty, tipping her $50 or $100, and then asking her out on a date. At that point, he will identify the woman’s vulnerabilities – love, poverty, heroin – that he can leverage to control her life.

Sometimes, fake “boyfriends” take advantage of impressionable young girls.

This was the case with Rachel Kaisk. Growing up in Barberton, Ohio, she was excited about a future as an equestrian. She was 16 and in the process of applying to the horse veterinarian program at The Ohio State University in Columbus when a slightly older and very friendly man talked her into going on a getaway weekend. It devolved into 15 years of subjugation.

According to Ms. Kaisk, the man coerced her into prostituting herself at a truck stop in Youngstown, Ohio; he got her addicted to crack, and then relocated her to New York and New Jersey for many years.

Kaisk eventually made it back to Cleveland in 1998, where she was able to escape that life and begin a slow process of recovery. She has regularly attended events at the Renee Jones Empowerment Center (RJEC) since she sought help roughly five years ago. Now, she’s become a public speaker for the center, sharing her story to help herself heal and keep others from becoming victims.

“I love Renee and don’t know what I would do without her, because she just gives you all that love and caring, and she helps you with anything,” says Kaisk.

In the United States, recognition of the extent of sex trafficking rose after Congress enacted the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act in 2000, which sought to both crack down on those who enslave people and provide greater support to victims. Ohio did not pass a law against the offense until 2010. Much of the concerted effort here, both before and since then, has come from activists like Jones, who find the thought of trafficking humans abhorrent and unconscionable.

In the mid-1990s, Jones was leading a comfortable life. She was working as a human resources manager at Medical Mutual, a Cleveland-based health insurance firm, and then transitioned to a similar position at the Great Lakes Science Center, a museum and educational facility. Her two children were both in college.

In her free time, she rode horses in parades and at Civil War reenactments as one of two women members of the Buffalo Soldiers, a group that honors the legendary African-American troops who fought for the Union Army. Yet working downtown, she was becoming frustrated at seeing all the homeless people wandering the streets who were not being helped. They were getting free meals, but little was being done to address the root causes of their plight. So she volunteered to conduct workshops on employment skills at a county center.

She taught people how to use computers at the library to write résumés and search for employment. She ended up placing 75 people in jobs.

“I learned firsthand from that experience that if you can get people who feel so hopeless to hope again, you open them up to a whole new life of possibilities,” she says. “You empower them to take charge of their lives, and I enjoyed seeing their lives renewed through the process.”

A friend told her about a vacant storefront in her neighborhood and pressed her to start a center to help the homeless. Jones opened the RJEC in 2002.

But, in doing her outreach work, she began to meet women and young girls working the streets who were facing much bigger problems than being homeless.

“When I saw how trafficked victims suffered at the hands of their traffickers physically and mentally, how most of the victims had no support or resources to help them get out of this life, I was compelled to create a treatment model to help victims recover and help them rebuild their lives,” she says.

Jones continued to work in human relations while helping victims of trafficking at night and on weekends. Then, last year, she received a grant from the Ohio attorney general’s office, which allowed her to work full time at the RJEC, where she spends 50 to 60 hours a week when she’s not roaming strip clubs.

The center serves as a one-stop shop for a variety of services that survivors of sex trafficking use to heal from the trauma they’ve endured by being forced to have sex with strangers, sometimes as many as 20 times a day. The victims usually have to deal with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and other related maladies.

To help them do that, RJEC’s Project Red Cord offers programs ranging from art therapy and mentoring, to legal and financial assistance, to free dental care and health classes. The center remains the area’s only nonprofit agency committed to providing life coaching and aftercare services to help break the human trafficking cycle.

“I have never met anyone who cares more, does more, and sacrifices more to help and empower victims of trafficking to live healthy, happy lives,” says Maureen Guirguis, who also obtained a grant from the Ohio attorney general’s office in 2016 to fund a human trafficking project at Case Western Reserve School of Law. “Renee truly is a visionary, a role model, and a hero to countless women and girls.”

Marilyn Cassidy is trying to help victims of sex trafficking in Cleveland as well but through a different venue – the legal system. In 2012, the municipal court judge attended a workshop in Chicago held by the National Judicial Institute on Domestic Violence.

She had regularly seen women coming through her courtroom who had alcohol and other drug problems and who were frequently the victims of domestic abuse. What she didn’t fully appreciate was that many of them were also being forced to work as prostitutes by human traffickers. She started to realize that all of the women’s problems were often bound up together – and required special attention to get at the underlying causes.

“Part of it was recognizing who these women are that are arrested for prostitution or a drug-related felony,” says Judge Cassidy. “It was also the recognition that these women are being victimized in different ways and that we were in a position as a municipal court to identify and directly impact some of these women by helping them address those issues.”

In 2014, she started a specialized court that dealt with victims of human trafficking. It was set up under a specialized docket program established by the Ohio Supreme Court. The idea was to not just lock up adult women who have been forced into prostitution but get them into drug or alcohol rehabilitation programs, safe shelters, and trauma counseling, as well as to connect them with places such as the RJEC.

The twice-a-month court sessions are certainly different from the standard adversarial courtroom clashes between lawyers. Before each gathering, Cassidy meets with her treatment team to review the case of every woman who will appear before her.

When the women enter the courtroom, they are offered coffee and an array of baked goods laid out on the table normally occupied by defendants and their legal teams. Participants who are already in jail for other offenses, such as drug possession or drunken driving, sit in the jury box in their prison scrubs.

When the court session begins, Cassidy steps from behind the bench, sans robes, and begins dancing to the B.B. King song “Better Not Look Down.” She encourages everyone to clap. She approaches each woman and shakes her hand or gives her a big hug, except for those who don’t want to be touched. “They’re used to being beaten down and ignored,” she says. “Especially since court traditionally is, ‘Do what I say or I’ll lock you up.’ ”

Then each woman steps up to a lectern facing Cassidy’s bench. Karen Stanton, the docket coordinator, reviews the details of each woman’s status, her successes such as landing a new job or a certain amount of time sober, and what she may still need to do, such as find a new place to live or receive more drug counseling. A public defender assists women with pending legal issues.

Cassidy makes her exchanges as conversational as possible, but she employs a no-nonsense, tough-love approach. One woman holds a baby she delivered three days earlier. When she gets flustered by the judge’s resistance to her desire to move to Florida before completing the program, Cassidy calms her by saying, “Relax. You just had a baby! We’ll figure it out.”

While Ohio may be doing what it can to help victims of sex trafficking, it is not being lenient toward the traffickers themselves. The Safe Harbor Law, passed in the state legislature in 2012, raised the penalty for trafficking in persons from a second-degree to a first-degree felony with a mandatory prison term of 10 to 15 years. Brian Vigneaux, who recently served as investigator for the human trafficking unit in the Cuyahoga County prosecutor’s office, says pimps used to actually boast about serving time in prison, because it gave them more street credibility and the sentences weren’t too long. That’s no longer true.

The retired FBI agent notes that the county has also formed an extensive regionwide trafficking task force that includes local and federal law enforcement agencies as well as social service groups.

“Departments are joining us because they get a lot of bang for their buck when they pursue a human trafficking charge rather than a penny-ante narcotics or promoting-prostitution charge,” says Mr. Vigneaux. “When you have a team of several guys working a particular pimp case, everyone uses his particular expertise to develop the case further, so it’s a lot quicker and more efficient.”

As much as courts and cops have cracked down on trafficking, though, experts say another key to eradicating the problem is public awareness. It helps to keep police and politicians focused on the issue.

One of the most ambitious efforts in this area is an organization that distributes posters and fliers and puts up billboards that proclaim the problem “Happens Here Too.” Founded in 2007 by Karen Walsh and Toby Lardie, the Collaborative to End Human Trafficking provides a range of education and advocacy services for the prevention and abolition of human trafficking.

The group teaches health-care officials how to support victims and provides training for hotel and restaurant staff so they can recognize when pimps are deviously plying their trade. Additionally, the collaborative acts as the lead coordinator for more than 30 agencies and groups that constitute Greater Cleveland’s Coordinated Response to Human Trafficking initiative.

“Our mission requires a multidisciplinary, victim-centered approach to educate,” says Ms. Walsh, who began her career as a teacher but became an attorney in her 40s. “Our work continues to evolve because this is really a generational change, since the crime isn’t new, but we’re changing how we look at an old reality.”

Despite all these efforts, sex and labor trafficking remain major problems in Cleveland and across the state. The increased use of the internet by pimps to recruit women has contributed to the difficulties. So, too, has Ohio’s opioid crisis, which is aggravating social problems of all kinds.

Jones and other experts agree that several things still need to happen to have any chance of reducing sex trafficking. One is encouraging even more collaboration among police and social service agencies.

Another is helping judges, cops, and others to recognize the signs of human trafficking so women can be treated as victims rather than criminals. More resources are also needed, they say, to house, counsel, and treat survivors.

But people like Jones are helping, one victim at a time, and often at considerable risk to themselves. At one strip club she and the volunteers regularly visit, gunfire erupted after an apparent botched robbery in November.

At another club, Magic City, two men ended up in a gunfight with Cleveland’s SWAT team in March. The security guard there won’t let the volunteers in with their gift bags anymore. He takes them at the door and gives them to the dancers.

Still, Jones is not one to focus on the dangers to herself. She’s too busy concentrating on the problem at hand. When she and others were training Kaisk, the trafficked survivor, to become a public speaker for the RJEC, Jones told the woman at one point:

“Every time you come to the center, Rachel, even though you may still be struggling and in pain, you’re helping someone. We’ve had many young girls, 15 or 16, who we couldn’t get through to. But when you shared your story as an adult who’d been trafficked, you helped save their lives.”