Small town tries to put lid on power of Big Trash

Loading...

| CHARLTON and SOUTHBRIDGE, Mass.

John Jordan’s three-bedroom home in Charlton, Mass., was once appraised to be worth $300,000. But a real estate agent recently told Mr. Jordan that his home was worth whatever a buyer was willing to pay. In other words, the realtor said, $0.

Less than a mile away in neighboring Southbridge, what was just a municipal landfill when Jordan moved here in 2001 has grown into the state’s largest trash depository. Over the years, it took in as much as 1,500 tons of waste a day – a lot of it from Boston.

“It wasn’t anything like that when we moved in,” says Jordan, pointing toward the landfill from his kitchen, where Poland Spring water jugs are stacked in the corner. “I never would have moved here if I knew it was going to get this big.”

Now, Casella Waste Systems, the regional company that manages the site, says the landfill is expected to reach capacity within the next year and wants to increase the size of the landfill. Some residents blame the landfill for odors and truck traffic, as well as contaminated drinking water – which led two environmental law groups to file suit Friday against Casella. But the landfill has also been an important source of income for Southbridge: Over the past 14 years, Casella has paid the town more than $36 million.

On June 13, Southbridge citizens will vote on whether they want the town council to enter negotiations with Casella to extend the size of the landfill.

“This city needs a fair shot to make a decision about its future,” says landfill manager Thomas Cue, who says the company negotiated a “great deal” for Southbridge, with the highest host fee rate in New England ($6 to $7 a ton) and free trash pickup for residents until 2027. “How bad would it be without Casella?”

Across New England, landfills are disproportionately located in low-income communities where there is cheap land and residents hold little political sway. If Southbridge residents vote against expansion, they will add their weight to two other Massachusetts towns who won improbable victories against proposed landfill expansions – Saugus, earlier this year, and Hardwick in 2007. A third victory could help encourage other towns in the Northeast facing similar moves.

Casella has spent more than $75,000 on everything from consulting to postage in a bid to persuade residents to support the expansion, according to a report John Casella filed to the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance on June 1. Meanwhile, the Committee Against Landfill Expansion has spent just under $3,500 on mailings, flyers, lawn signs, and related costs, according to a similar form filed to the same office.

“If any community can do the David and Goliath fight and go against a company who is trying to buy them, that’s amazing,” says Kirstie Pecci, an environmental lawyer with the Conservation Law Foundation and a resident of nearby Sturbridge. “That is the best part of the human spirit and it makes me feel like there’s hope.”

A pattern of landfills in poor towns

Nationwide, poor communities tend to bear the brunt of environmental problems, including landfills, industrial waste sites, and other hazardous disposal facilities.

Southbridge, home to 17,000 residents, is ranked as Massachusetts’ 10th-poorest town. Among adults 25 years and older, only 16 percent of Southbridge residents have a college education.

“This would never happen in Wellesley,” says Sturbridge Board of Health Chairman Linda Cocalis, referring to one of Boston’s wealthiest suburbs. “Never.”

It's a pattern that is apparent throughout much of New England.

New Hampshire has six active landfills: one, in Success, N.H., population zero, and five others in areas with poverty rates above the state average.

Likewise, more than 60 percent of Maine’s landfills are located in poor communities and its largest is located in Old Town, where the poverty rate is 27 percent – double the state average. And Vermont’s only active landfill is in Coventry, a community with a poverty rate of 20.2 percent, also roughly double the state average.

Private waste companies are looking to be “economically efficient and politically expedient,” says Daniel Faber, director of Northeastern University’s Environmental Justice Research Collaborative (NEJRC) in Boston. This means choosing host communities with lower education levels and less time, money, and resources to mobilize themselves, he says. “They are less likely to offer opposition.”

Resident: 'It's not all about the money'

Casella tries to be a good neighbor, says Mr. Cue, while driving in his Ford pick-up around the landfill’s dirt roads.

The landfill closes early on hot days to avoid excessive smells, and Casella prohibits trash trucks from driving through the town during early morning hours. They also capture methane emissions from the landfill and transfer it back into the local energy grid.

“Many of the people are just afraid about what a landfill is,” he says, explaining how Casella captures the leachate – essentially the liquid that oozes out from the bottom of a trash heap – in tanks and then sends it to a wastewater treatment plant. “This is a scientific business.”

While other cities in Massachusetts put their trash on the curb, says local resident Pamela Paquin, Southbridge has the opportunity to manage its waste responsibly, and become an environmental leader. Southbridge could make even more money off of the landfill by separating recyclable materials that could be resold.

“You just need the mind-set to see a point of conflict as an opportunity to create something useful,” says Ms. Paquin.

But at a May 22 town council meeting in Southbridge, all who spoke had questions or concerns about the potential landfill expansion. Southbridge mother Erin Lapriore invited the town councilors to come to her home at 7:00 a.m. as she waits for the school bus with her children while the trash trucks speed past.

“It’s not all about the money, it’s the quality of life,” said Southbridge resident Kevin Buxton. “What are we leaving our children?”

Ms. Pecci says zero-waste programs could deal with as much as 80 percent of the waste currently being generated. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh recently announced his intention to implement such a program.

'We know what we can be again'

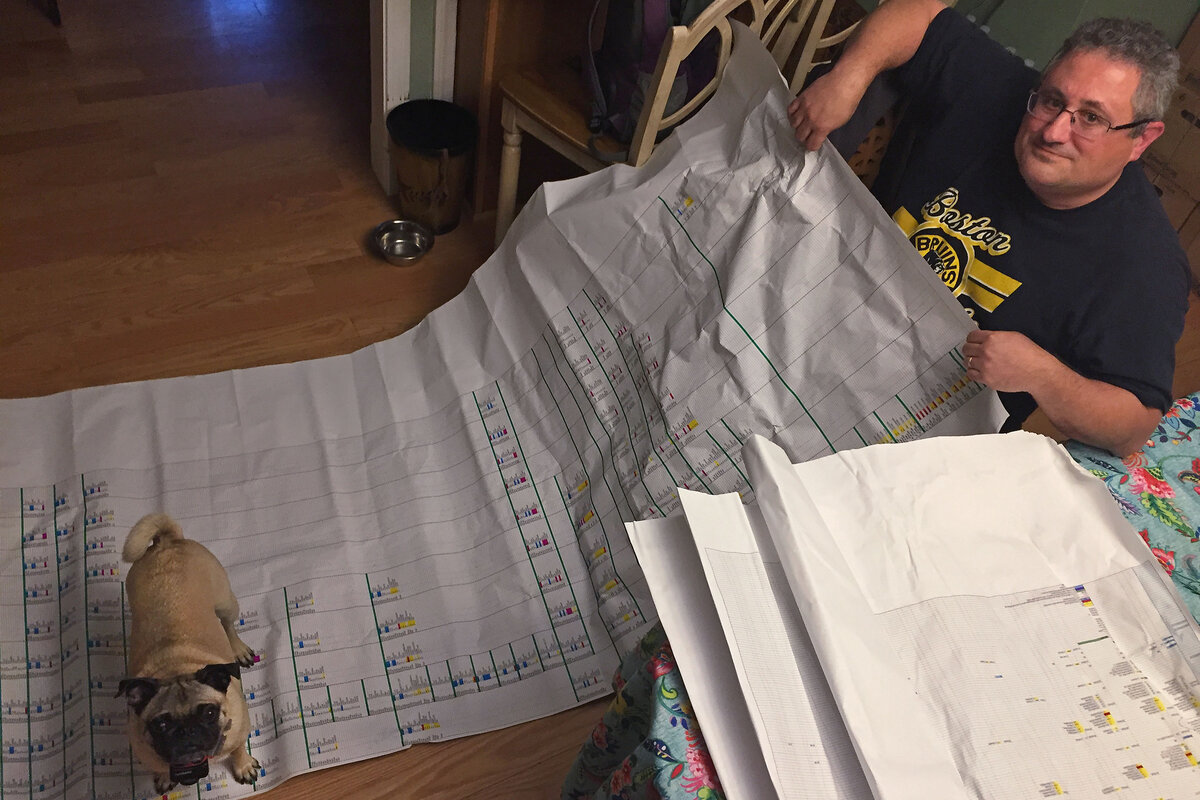

Back in Jordan's kitchen, he says he never really considered himself an environmentalist kind of guy. But he says when chemicals from the landfill contaminated the wells in his neighborhood, he founded the local activist group CleanWells.org.

The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has not blamed Casella for the contamination, but the DEP has been unable to find any other possible sources. As a result, Casella supplies 33 homes in Charlton with bottled water. Only 15 are mandated by the state, notes Cue. The rest, including Jordan’s home, are “courtesy.”

But despite Casella’s paychecks and donations, the landfill has brought down the self-esteem of the entire area says Town Councillor Kristin Auclair, a lifelong Southbridge resident.

“We need to rid ourselves of this baggage to fully move forward,” says Ms. Auclair, who was inspired to run for public office because of the landfill. “Our identity should not be the landfill... Those of us who are still here and still fighting see the potential, and know what we can be again.”