Cassette comeback: For fans, 'a yearning for something you can hold'

Loading...

Like the original, “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2” is endearingly retro. The hero Peter Quill (Chris Pratt) cherishes a vintage Sony Walkman and his mixtape of 1970s pop gems such as “Brandy (You’re a Fine Girl)” from the band Looking Glass.

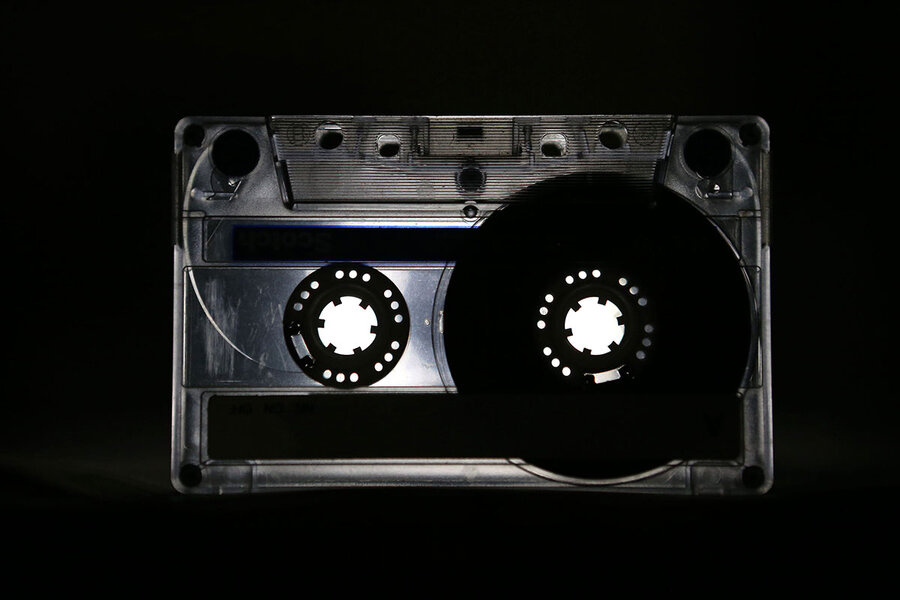

The cassette is part of writer-director James Gunn's homage to the Analog Era. But tapes are hardly obsolete or even passé. While they may have disappeared from many record store shelves, tapes haven’t gone away. In fact, they’re back in a big way. Cassette sales are up by 82 percent for the year, and even Top 40 hitmaker Justin Bieber is releasing albums on tape. The “Guardians of the Galaxy” franchise is aiding the revival, too. When the original soundtrack dropped in 2014, the tape edition became the best-selling cassette record since 1984.

Sure, there’s a certain amount of nostalgia at play here and Millennial curiosity for what music sounds like without earbuds. But for the growing number of fans, labels, and musicians who are driving a cassette boomlet – and the much larger vinyl revival – there seems to be a yearning for music that offers a much fuller and more tactile experience, something that goes beyond the digital bits that feed nonstop streams from services such as Spotify and Apple Music.

“I think it’s a desire for more,” says Damon Krukowski, author of the new book “The New Analog: Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World.” This renewed musical interest is about seeking out “fuller communication,” he says. Since digital streams can’t carry complete album artwork, liner notes, lyrics, or back cover credits, listeners are looking for parts of that music experience that extends beyond individual tracks on digital playlists.

“There’s a whole layer of meaning that also disappeared with the disappearance of the physical form,” he says. “It’s only when you have the full picture that you have full meaning.”

In many ways, it's the generation raised on an everything-digital media diet that's heralding the revival of the tangible. And it's not just music, either. Some recent studies have shown that 20-somethings prefer reading books on paper instead of on tablets, a trend that's helping keep many small booksellers alive. There's a renewed interest in the thing, as Mr. Krukowski points out, because the medium can be as valuable as the media itself.

Indeed, packaging and design is a premium in the new vinyl and cassette wave. For instance, the deluxe edition of Radiohead’s 2016 “A Moon Shaped Pool” includes a bound, 32-page art book. Indie cassette releases often contain limited edition posters and bonus tracks.

But there’s more to the analog format than album art, says Krukowski. In his book, he also argues that there’s just too much sterility in today’s digital music. While new recording technology can eliminate much of the noise that was once commonplace (and even cherished by audiophiles) in analog records, it's that kind of distortion – from the recordings as well as from record players and tape decks – that creates more memorable and meaningful listening experiences.

“Analog sound reproduction is tactile,” wrote Krukowski, who is one half of the musical duo Damon & Naomi and drummer for the influential 1980s indie rock band Galaxie 500. “It is, in part, a function of friction: the needle bounces in the grooves, the tape drags across the magnetic head. Friction dissipates energy in the form of sound. Meaning: you hear these media being played. Surface noise and tape hiss are not flaws in the analog media but artifacts of their use.”

For anyone who remembers when cassettes were commonplace, and every car had a tape deck, you'll know their characteristic hiss and squeak from dirty tape heads. And beware the cassette jam, and the tangle of tape. The medium wasn't known for superior sound. But the quality of new cassettes has improved since their heyday, largely because of better mastering equipment, says Steve Stepp, president of National Audio Company, the world’s largest producer of professional audio cassettes.

The company expects to turn out some 24 million tapes this year, a 20 percent jump from last year. “We’ve seen an amazing resurgence,” says Mr. Stepp. “Downloading from the cloud may be convenient, but it doesn’t give you anything to hold in your hand or trade with your friends,” he says. “There’s a yearning to have something in your hand.” And, he says, “you are listening to true analog sound.”

Many audiophiles still shun the cassette as the lesser music format, and not offering the warmth of vinyl, but on the right equipment (if you can find a good player) the tape still provides a richer and more immersive listening experience than CDs or digital streams.

It's the kind of sound that many recording artists are going to great lengths to capture in their music, whether it's heard over the internet or on a turntable, says Berklee School of Music associate professor Susan Rogers. One example, she says, is the Feist song "Undiscovered First" from her 2011 album "Metals." On that track, Feist uses open microphones in the studio to the capture background and ambient sound. "It evokes an emotional response that’s wonderful," says Ms. Rogers, who teaches analog recording.

Beyond the sound, she says, the physical medium forces listeners to experience music in active ways, as opposed to what she calls "auditory wallpaper," music that flows through commuters' headphones or in the background at home. "An active listening experience is where you commit to listening.... You’d put the vinyl on and you were captive to it."

Sales still tiny

Physical music sales are minuscule when compared with digital music consumption. BuzzAngle, a firm that charts music sales, recorded 83.6 billion music streams so far this year, a 60 percent hike from the same period in 2016. Meanwhile, in the first quarter of 2017, it registered 11,000 cassette sales, a 64 percent jump from the same time last year. During the same period this year, vinyl sales hit 1.8 million (up 22.5 percent) and CD sales came in at 17 million (down 11 percent). All categories of music sales are down except vinyl and cassette.

Much of the cassette trade, however, isn’t happening via major labels or mainstream retailers. Fans are grabbing inexpensive tapes (usually around $5) at merchandise tables at indie rock shows and via obscure online music retailers, places where it's difficult for groups such as BuzzAngle to gauge sales. At the Newbury Street location of Boston record store chain Newbury Comics, the store had just 33 cassettes for sale on an out-of-the-way shelf. The days where the record stores displayed walls of cassettes (and remember those tape suitcases?) are long gone.

“If an album is available on cassette or vinyl, I will always buy the cassette,” says Britt Brown, a Los Angeles musician who also runs the record label Not Not Fun. “It’s just the medium I prefer.” It’s durable and fun, he says. “There’s something that’s less serious about a cassette. If you crack the shell of a cassette, you just get a new one.”

Though Millennials like himself, who grew up buying CDs, may be leading the cassette revival, the medium still appeals to fans raised on tapes, he says. “I think it has more to do with one’s overall passion for music and a bit with enjoying the collectibility of it and the merch.”

There’s also the simple utility of the cassette. The vinyl comeback has the few remaining record-pressing plants struggling to fill orders. That means smaller labels and independent artists can wait as long as a year to get a vinyl record made.

“Cassettes are faster, and cheaper, and easier to get out,” says Sean Byrne of Endless Daze, a cassette devotee who helps run a Philadelphia punk label that hand-prints all of its tape covers. “We put out tapes because you can get a tape done in a month,” he says. And it’s what many concert-goers want to take home after the shows, he says. “Honestly, you couldn’t even sell a CD at this point.”

It's also worth noting that the new crop of tape buyers aren’t just listening to music on one format or medium, says Mr. Brown. “No matter how powerful Spotify and things like that become, and how convenient that is, there will always be people who want physical music. Or, who want both.”