Is edgier political comedy making America worse?

Loading...

| NEW YORK

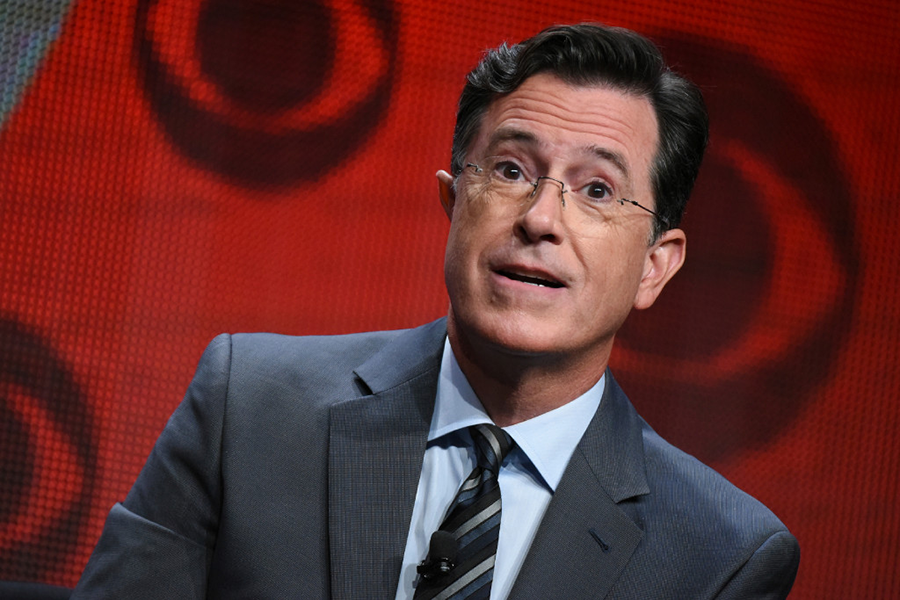

When late-night comedian Stephen Colbert hurled a string of crude insults at President Trump on “The Late Show” last week, it didn’t take long for the leader of the free world, a former reality-TV star, to respond.

Conservative critics and others were calling for Mr. Colbert’s ouster this week after the nation’s most-watched late-night host used a lewd metaphor to close out his litany of scornful president-dissing puns. An insult of the “locker-room banter” variety, Colbert’s final quip was criticized by LGBT advocates, some of whom said his joke was a symptom of a wider culture of still-accepted homophobia and joined the #FireColbert furor.

“There’s nothing funny about what he says,” the president told Time magazine, calling the host a “no-talent guy.” “And what he says is filthy. And you have kids watching. And it only builds up my base. It only helps me, people like him.”

From political cartoons a century ago to the conventions of parody and satire on late-night TV, insults hurled are hardly anything new in American politics. Yet critics from the right and left are both expressing concern about a new edginess to the humor – an edginess that may thrill each side’s base, but also deepens cultural divides.

And many say Trump is right about one thing: The comedy of Colbert and other liberal-leaning late-night comics has only helped the president. Both Trump's supporters and other conservatives say they see an infuriatingly smug, know-it-all style on the American left – and especially among the liberal comedians who cater to them.

“We’re all familiar with the style,” wrote David French in The National Review, critiquing the likes of HBO’s John Oliver and TBS’s Samantha Bee, both alums of Comedy Central’s genre-changing news parody, “The Daily Show.” “The basic theme is always the same: Look at how corrupt, evil, and stupid our opponents are, look how obviously correct we are, and laugh at my marvelous and clever explanatory talent.”

Yet many social critics see more than hectoring and propaganda behind the changing traditions of America's political satire. From the niche audiences of digital media and cable news to the varying comedic sensibilities of urban and rural viewers, a new media landscape has begun to evolve, scholars say.

“For the guy who goes and works 50 hours a week just trying to make ends meet for his family, and he just wants to sit down and watch the 11 o’clock news and laugh a few times before going to bed, there’s this feeling now that everything is political,” says Heather LaMarre, an associate professor at the Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University in Philadelphia. “People just don’t have an escape, and they’re frustrated that they don’t have an escape.”

Indeed, for those who would “make America great again,” the current dominance of aggressively liberal comedy feels like another culture loss. And late-night comics are seen as “Hollywood elites,” as powerful as the people they are mocking, many believe. The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote before the election that late-night comics had abandoned the witty, winking satire of a Johnny Carson or David Letterman, in favor of hosts who are “less comics than propagandists – liberal ‘explanatory journalists’ with laugh lines.”

Make no mistake, former late-night comics like Mr. Carson and Mr. Letterman tossed plenty of insults at politicians. But Professor LaMarre points out that their dominant rhetorical style of was what scholars call “Horatian satire,” named after the 1st-century Roman satirist Horace, and characterized by a wit that criticized human folly in a tolerant way.

Today, however, most of the late-night comics have begun to employ a more “Juvenalian” style of satire, named after the 2nd-century Roman satirist Juvenal, and characterized by a more angry, personal, and indignant exposure of vice and folly. Comics such as George Carlin, Lewis Black, and the conservative Dennis Miller employ this style.

“Each of the current late-night satirists are competing for viewers and for the sort of relevance that only comes from being GIFfed, memed, retweeted, or posted to Facebook,” says Steven Benko, an assistant professor of religious and ethical studies at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C., who studies the ethics of humor. “They have to be louder, more pointed, and they have to find a niche that distinguishes them from the others. Being loud, being biting is how they attract viewers, and they are up against cable where the rules on language and content are looser.”

Among comedians, one of the most biting forms of humor remains the genre of schoolyard-style disses – rhetorical battles of wit and humor that up the ante for often lewd, personal taunts.

It’s a genre Mr. Trump knows well, too, having been the witting subject of a Comedy Central roast, where most jokes bring as many bleeps as laughs. And the president himself employs name-calling, including crude and profane insults, as no American leader ever has before. Colbert’s rhetorical litany of insults, in fact, was meant to be a response to the president’s quip to CBS’s Face the Nation host John Dickerson – or, “Deface the Nation,” Trump said during an interview last Sunday.

“When you insult one member of the CBS family, you insult us all!” Colbert began. “Mr. President, I love your presidency, I call it ‘Disgrace The Nation.’ You’re not the POTUS, you’re the ‘gloat-us.’ You’re the glutton with the button. You’re a regular ‘Gorge Washington,’’ he said, before becoming more biting and lewd.

Critics note that before Trump was elected president, Colbert struggled to find his comedic voice as Mr. Letterman’s replacement on “The Late Show.” When he played a parody of a conservative Bill O’Reilly-like host in his Emmy-winning “The Colbert Report,” he had a more Horatian style of satire.

But as he and others became more aggressive toward the new president, their ratings shot up.

The number of politically liberal viewers tuning in to Colbert doubled since the election, researchers say. Samantha Bee’s “Full Frontal,” too, has become the most-watched late-night show among viewers 18 to 34 years old – just one year after its launch.

Yet not too long ago, some observers note, the angry style of political humor was the realm of conservatives. Rush Limbaugh, in fact, uses aggressive parody and satire in his long-running radio show. And with advertising lines such as “talent on loan from God,” Limbaugh has been a leading conservative voice grounded in a comic style. The pundits Ann Coulter and Glenn Beck, too, have used a mocking schtick in their personality-driven takes on politics.

“Jokes, commentary, or satirical bits that absolutely enrage one side leaves the other side laughing so hard that people's ribs hurt,” says Brian Rosenwald, a media scholar at the University of Pennsylvania. “My line to lots of conservatives complaining about Stephen Colbert last week, and calling on CBS to sanction him, was to question whether they thought Sean Hannity and Rush Limbaugh should be sanctioned by their bosses for some of the outrageous and inflammatory things they say.”

But as political satire and late-night comedy becomes more aggressive and Juvenalian, it risks becoming less effective, says LaMarre.

“People will pay more attention to satire that is dark and edgy, but they will also argue against it more,” she says. “So although more people will pay attention to it, it will have much less of a persuasive impact.”

But as long as Trump remains the insulter-in-chief, few see this shift in political satire changing soon.

“The whole game has changed now – there’s a new dealer at the table, and it’s not any kind of dealer that we’ve ever had before,” says Christopher Irving, who teaches English and the humanities at Beacon College in Leesburg, Fla. “If Donald Trump were a seasoned politician, a statesman, and not a successful billionaire who likes to Tweet all the time, we would still be having the same arguments, but in a very different way.”