Why so much blatant racism is bubbling to the surface

Loading...

| Atlanta

The firing of a teacher’s aide in Forsyth County, Ga., the censuring of a small-town mayor in Pennsylvania, the arrest of an East Tennessee State University student – all three after comparing black people to apes.

These recent examples of blatant racism have been met by swift public condemnation. Americans, on the whole, remain firmly intolerant of intolerance.

But shudders of racist sentiments in times of civil unrest are hardly new, and the current bout is noteworthy, say some ethicists and historians.

The racist speech is accompanied by an emboldening of white supremacist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan – which grew from 72 chapters in 2014 to 190 last year, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. They’ve been actively recruiting, leafleting lawns and sidewalks in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and California. And former Grand Wizard David Duke is running for the Senate in Louisiana, saying his platform has “become the GOP mainstream.”

The trend is partly a new age manifestation of age-old problems – in essence transferring what used to be anonymous wall scribbles to the center of the public square. Indeed, some are seeing the First Amendment right to free speech as an invitation to incite.

But in that way, social media – along with the racially charged nature of this year’s presidential election – are forcing the most entrenched forms of racism to the surface in new ways. While shocking to some to hear, the outbursts give a more accurate portrayal of how much further America needs to go to heal race relations – and can sometimes be a catalyst to accelerate that progress, some say.

“These remarks tell us there’s a strong strain of bigotry and racism still alive in our country,” says Gene Policinski, senior vice president for the First Amendment Center in Nashville. “Sometimes the function of free speech is to give us a true picture of society.”

The evolving shape of civility

The recent incidents have captured attention, but also spawned a backlash.

On Facebook, West York, Pa., Mayor Charles Wasko, has compared the Obama family to orangutans and has suggested President Obama should be lynched. He remains unrepentant, claiming a “witch hunt” against him. “The racist stuff, yeah, I’ll admit I did that, and I don’t care what people label me as,” he told WHTM-TV.

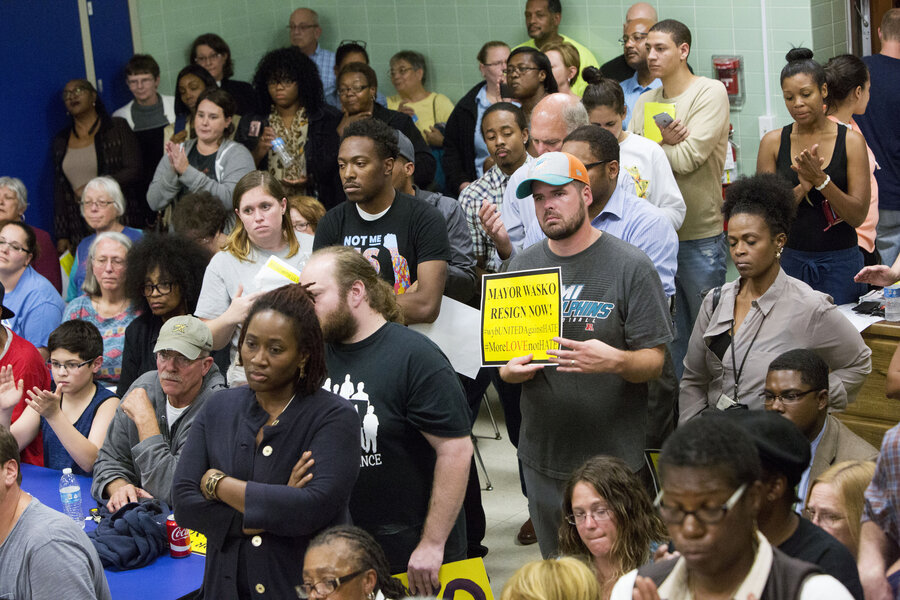

During an emergency town hearing on Monday, many residents said the tone of the presidential race is giving license to racist rhetoric. Pennsylvania state Rep. Kevin Schreiber (D) called Mr. Wasko's Facebook outbursts “the legacy of angry, bigoted speech and rhetoric that is so quickly and casually spewed and circulated today.”

Meanwhile, school officials said a teacher’s aide in Georgia’s Forsyth County made repeated comments likening first lady Michelle Obama to a “poor gorilla.” The school district acted decisively to fire her.

For his part, the East Tennessee student was charged with one count of civil rights intimidation, a crime in Tennessee. He admitted to trying to provoke a largely African-American crowd to violence by wearing a gorilla mask and carrying a banana on a string, which he offered to black people, saying, “Here you go, sir.”

While extreme, in many respects, these incidents point to a debate over the shifting bounds of civility. They are in part a backlash against the perception of political correctness run amok. The rise in discussion on college campuses of “micro aggressions” (sleights caused by racial insensitivity) and “trigger warnings” (that warn survivors of rape or abuse of depictions in books, art, or movies that could “trigger” a reaction) is seen as a prime example of sacrificing robust free speech for cultural oversensitivity.

The incidents point to the growing willingness among some Americans to challenge these emerging social norms and boundaries. And Donald Trump, with his brash style, has helped lead the charge.

“What Trump has done is emboldened a number of individuals and groups who might hold similar views to express them in a way that would not have been socially acceptable only a couple of months ago, never mind a couple of years ago,” says Joshua Inwood, a geographer and ethics core faculty member at Penn State in University Park, Pa. “The election of Obama and [rise of] Trump has unleashed a whole set of discourses that were obviously prevalent in the United States of America, but were not given such mainstream play.”

To critics, the trend has simply been an attempt to find acceptable means of public expression for latent racism.

“Broader attacks on ‘political correctness’ are simply an attempt to hide the sentiment that whites are mad that they don’t get to speak any way they want to in offensive, horrible, dangerous, threatening and illegal ways about folks of color,” says Matthew Hughey, a University of Connecticut sociologist. “Trump is drawing from that well.”

The danger is that the incidents may not remain confined to verbal attacks. “Upticks of rhetoric … tend to end in some kind of violent outburst,” says Professor Inwood.

Response to the incidents

But the backlash against such rhetoric can also have a positive effect in the longer term. The tragedy of the 1906 Atlanta race riots, which were fanned by incendiary racial rhetoric whipped up by competing newspapers, resulted in the creation of committees of black and white leaders that became the early blueprint for the civil rights movement a generation later.

The 1906 riots also resulted in public censure of the most incendiary of the newspapers, the Atlanta Evening News, which closed weeks after the violence.

In West York, the town council voted Monday to censure Mr. Wasko. Hundreds of residents packed the meeting to voice their disgust. “He left no one behind in his hate,” town council president Shawn Mauck told reporters.

And the reaction to the gorilla-masked young man in Johnson City, Tenn., also spoke volumes. The largely African-American crowd ignored the man's provocations until police arrived to arrest him.

“There may in part just be a perception that there’s more people speaking [racist thoughts] now that they have a [social media] amplifier that they didn’t have in the past,” says Mr. Policinski at the First Amendment Center. “I think we’re right to take it seriously, and we have every right to be offended. But I also think there is some value in hearing this in the marketplace of ideas even though it brings pain and embarrassment and shame to those who think this language is out of bounds.”