Ferguson's legacy: for blacks, empowerment amid sense of injustice

Loading...

| Atlanta

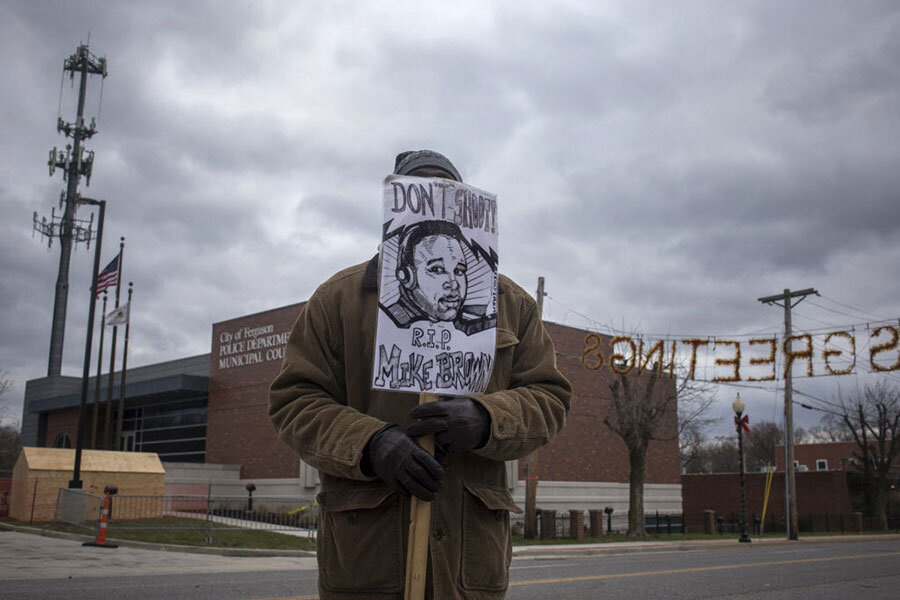

The wrenching and at times violent national conversation about race since Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Mo., a year ago has offered a glimmer of hope to some in the black community, kindling a fresh sense of empowerment amid continuing concerns about injustice.

At the time, views of the Aug. 9, 2014, killing of Mr. Brown, a black teen, by white Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson sharply divided white and black Americans. But new polls show a stirring of thought on the issue of race, suggesting that the efforts of the past year – including the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement – have had an effect.

Some 53 percent of white Americans surveyed by the Pew Research Center said that the country needs to continue changing to give blacks equal rights. Last year, the figure was 39 percent.

Similarly, a new Gallup poll shows that the percentage of whites who say they are satisfied with the way blacks are treated dropped from 67 percent in 2013 to 53 percent this year. Between 2001 and 2013, the percentage of whites who said they were satisfied with how blacks are treated never dipped below 63 percent.

During the past year, some 40 measures aimed at curbing police abuses have also been introduced in state legislatures. And the tragic killing of nine black churchgoers by a white supremacist in Charleston, S.C., in June resulted in a strong nationwide backlash against the Confederate battle flag, including its removal from the statehouse grounds in Columbia.

This ferment has at least temporarily opened a new sense of possibility among black Americans, some analysts say.

“Social movements don’t just change policy, social movements also change the people who participate,” says Clarence Lang, chair of African and African-American Studies at the University of Kansas and author of the new book “Black America in the Shadows of the ’60s.” “Having a sense that you can intervene in the course of events and change the dynamics can be very powerful and, strangely, it can be a very uplifting feeling.”

The one-year anniversary of Ferguson comes as Gallup finds that black Americans are reporting their highest levels of personal life satisfaction in 14 years. Last month, 88 percent said they are very or somewhat satisfied with their lives, for the first time topping the corresponding number for white Americans (87 percent). In 2008, black satisfaction hit a low of 80 percent.

The rise may not have anything to do with the Ferguson fallout. A different Gallup poll found that black satisfaction at how they are treated in American society dropped to 33 percent this year from 47 percent in 2013. That’s the lowest mark since 2007.

But that contradiction seems to be a part of Ferguson’s legacy. One of the Gallup polls found that blacks don’t think they’re being treated less fairly now than in the past. For his part, former Officer Wilson was not indicted by a grand jury and was cleared by a federal investigation. Yet, Ferguson, it seems, has brought a keener sense of both injustice and empowerment.

“Blacks in Missouri were essentially reduced to staying in our place and understanding that we must never step out of line when dealing with a white person,” writes the poet and activist Tef Poe in the River Front Times in St. Louis. But now, he adds, “the sleeping giant has … risen, and the result is a movement for black lives that has spread across the world. Your system does not have to embrace us; we are simply asking to be released from the confines of your jaded perspectives.”

Some black Americans polled by the Associated Press ahead of the Ferguson anniversary said they have seen hints of progress in race relations.

David Thomas of Vienna, Ga., said he remembers being roughed up by police in Savannah, Ga., when he was a young man, but that relations between law enforcement and black residents have since improved, at least in his eyes.

“Everything is not right, but it’s better,” Mr. Thomas said.

The AP poll pointed to one of the drivers of racial tension: segregation.

It found that white Americans living in diverse communities – where at least 25 percent of the population is not white – saw the issue of police use of force differently from those who lived in more segregated communities. In the diverse communities, 42 percent of whites said police can be too quick to use deadly force on black people; in the less-diverse communities, the number was 29 percent.

In general, sharply segregated cities such as Ferguson stand in contrast to broader demographic shifts, with many American neighborhoods becoming more diverse. Only exurbs on the far urban fringe are becoming noticeably whiter, according to the most recent census.

“The 2010 Census gives strong hints about where we are heading, which in the best of all worlds – and in hopeful contrast to many other parts of the globe – will involve continued growth, youthful vitality, and a reinvention of the melting pot that characterized our country at the beginning of the 20th century,” demographer William Frey wrote in 2011.

What effect that has on the lives of black Americans is likely driven by local factors, says Colin Gordon, a labor historian at the University of Iowa and author of “Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City.”

“Segregation indices, even in St. Louis and Baltimore, are coming down and gradually diminishing, but I think what that means on the ground in a particular metro setting varies considerably, and that has to do with all kinds of legacy issues, including the degree and sustainability of economic growth," he says.

The past year, from Ferguson to Charleston, saw communities move to a new level of engagement and action on race.

“If we think about what happened in the aftermath of the George Zimmerman verdict, where a young man is shot under [questionable] circumstances, a great number of African-Americans really found it disturbing and distressing that [Zimmerman] was acquitted. There’s this complete sense of impotence," says Professor Lang. “And you contrast that with what happened in the aftermath of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray [in Baltimore], where there is this mass response. We have death in all these cases, but I think what distinguishes what’s happened in the past year to what happened in 2013 is that people were resolute in responding.”