Do kids today have too much homework?

Loading...

| Nashville, Tenn.; and New York

To Samson Boyd, a father in Nashville, Tenn., simple addition used to be a straightforward proposition: Four plus four equals eight. But in today’s era of newfangled math, kids are taught various ways to arrive at the right answer.

So when Mr. Boyd was helping his 10-year-old son with arithmetic one night recently, he needed help and called the Homework Hotline, a Nashville program that provides free tutoring for students and parents. His was one of about 12,000 such calls the hotline has fielded this school year alone. It’s a reminder of how demanding the workload can become for kids and raises an enduring question: Is too much late-night calculus and chemistry overloading young people today?

Any way you look at it, homework is a fraught topic. In education policy circles, some argue it is an unnecessary, ineffective intrusion that penalizes kids who have no Internet or adults able to help at home. Others maintain it helps children learn and provides a bulwark against too much television. While homework overload certainly exists, an in-depth study by the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy found it affects only 10 to 20 percent of families.

Still, even in households where it is welcomed, homework can cause distress. In a 2013 survey by the National Center for Families Learning, 60 percent of parents admitted they were sometimes unable to help their child with homework. In Nashville alone, more than 30 tutoring agencies, numerous academic enrichment programs, 200-plus private tutors, a network of free after-school programs at 44 sites, and 24 teachers plus student volunteers at the Homework Hotline address the homework and test-prep woes of the city’s 105,000 school-age kids.

One of the main reasons people sign up with the Nashville Adult Literacy Council, says executive director Meg Nugent, is “to help their kids in school.” Some immigrants speak too little English to help their children with homework, and the American-born who have grown up speaking English but cannot read – or at least not well – don’t want their children to suffer the way they did in school and in life generally; they want to become literate themselves so they can help their kids.

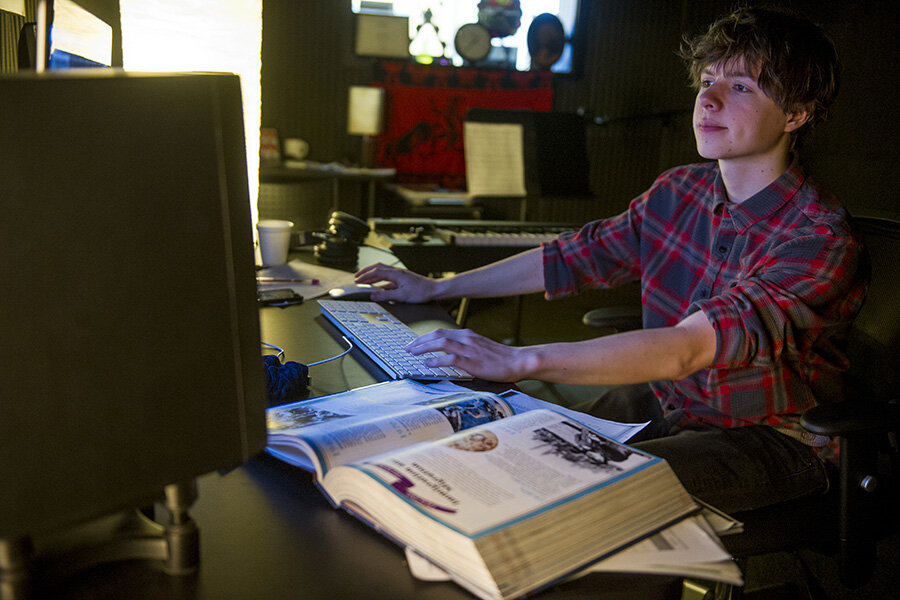

Often it’s not the amount of homework that causes tensions but simply getting kids to do it. Chas Plummer, a divorced father in New York, had no beef with the workload his son, Parker, had to do at night, but he hated having to continually ask, “ ‘Did you do your homework?’ Parker would say ‘yes,’ but the work was back in his school locker,” Mr. Plummer says. Sparks would fly. “It just became horrible at home.” Peace descended after Parker enrolled at Fusion Academy, a nontraditional private school in Brooklyn. Parker has reengaged with academics through its one-on-one classes, and “homework” stays on campus. After Parker and English teacher Kim Essex discuss character, plot, and symbolism in the book “A Game of Thrones” on a recent day, she assigns him reading and an essay. Totally cool with this, Parker saunters into the open area used as the Homework Café and plops onto a couch.

Parenting columns routinely recommend setting aside a quiet place at home to do such work, but the advice seems quaint in today’s fragmented world. Parker does his work in the semi-quiet of the Homework Café, getting a teacher to sign off on it before he heads home.

Children in after-school programs gather in groups for an allotted time, while other kids squeeze homework into the interstices of a busy schedule. Since 2004, middle-school teacher Judi Fox has conducted 12,588 tutoring sessions at the Homework Hotline. Kids, she says, call “from the car, from hallways outside dance studios, from a bathroom, from every possible location.”