The new 'cool' cities for Millennials

Loading...

| Baltimore

When Clara Gustafson, a recent graduate of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., told her friends that she was moving to Baltimore, a lot of them looked at the 24-year-old as if she were crazy. “You’re going to live in The Wire!” the Portland, Ore., native remembers them saying – a reference to the HBO series focused on the illegal drug trade, set in her soon-to-be hometown. “I didn’t know what to expect,” she says.

But Ms. Gustafson had snagged a prestigious fellowship with a new organization called Venture for America, which matches talented young people with start-up companies in cities such as Detroit, Cincinnati, and Providence, R.I. – cities that are not traditional magnets for college graduates. And she was thrilled when she got a job offer from a cybersecurity start-up called ZeroFOX, based in one of Baltimore’s downtown neighborhoods. So she packed up and moved to the town that boosters call Charm City, and that others have dubbed Bodymore, Murderland.

But rather than being a pioneer, Gustafson quickly realized that she had moved to a city that is full of other young professionals – and attracting more every month. There is a vibrant bar and restaurant scene, social sports leagues through which hundreds of young people get together to play kickball and other games, even a monthly bike ride – sponsored by a group working to make Baltimore less car dependent – in which participants dress up in costume and ride through the city.

Add to this some great downtown architecture, a relatively low cost of living, and a slew of new, innovative businesses that promise young workers the immediate chance to make a difference, and Baltimore, she realized, had become surprisingly “in” to her demographic. “There are a ton of young people,” she says.

Baltimore is not alone when it comes to, well, uncool cities that have become – sometimes to the shock of long-term residents – hip.

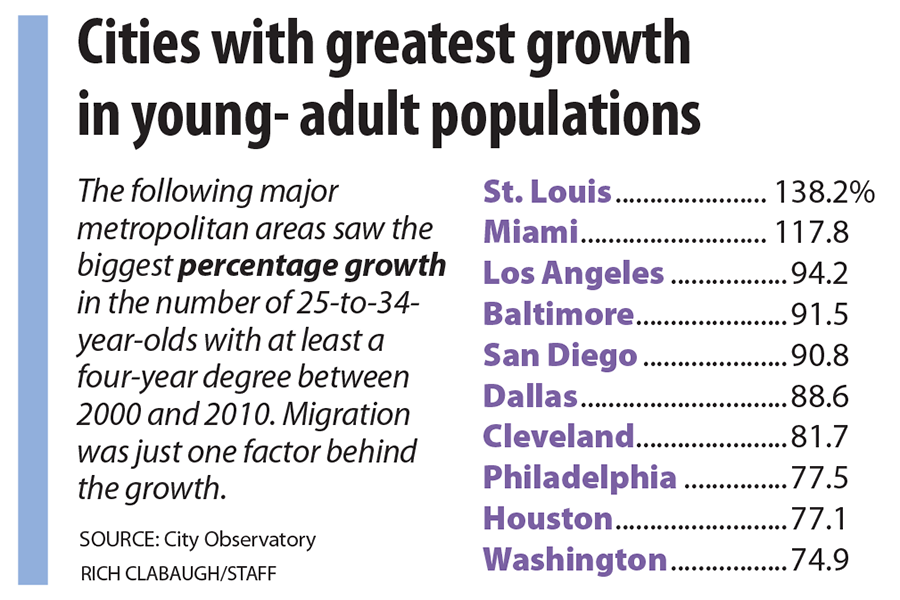

While the traditional urban magnets for college graduates – San Francisco, New York, Boston, Seattle – still attract the largest number of degree-holding Millennials, the “hottest” cities are elsewhere. These are places such as Cleveland, where 20-somethings are snapping up downtown apartments as soon as they hit the market; St. Louis, which has seen a 138 percent increase in the percentage of educated 25-to-34-year-olds living in close-in urban neighborhoods between 2000 and 2012; and Nashville, which saw a 37 percent increase between 2007 and 2013 of those people born between 1977 and 1992, according to a report by the housing research group RealtyTrac. (See related story.) Even Detroit, long considered an urban dystopia, increased its Millennial population by nearly 7 percent between 2010 and 2013.

In Baltimore, the number of degree-holding young people living in core urban neighborhoods increased by 92 percent between 2000 and 2010. Today the city’s downtown boasts one of the fastest-

growing residential populations in the region. (The area, historically the central business district, has become known as the 401, after its census tract number.)

“I have a board member who remembers being on Pratt Street in the 1980s and said, ‘You could shoot a cannon and not hit any-

one,’ ” says Kirby Fowler, head of the nonprofit Downtown Partnership of Baltimore, talking about one of the city’s main thoroughfares. He laughs. “Now you see joggers. More joggers. And more dogs.”

These urban areas may not be traditional magnets for young people. But cities like Baltimore are, in many ways, the best places to look to understand both how the country’s long-beleaguered cities are changing, and how the Millennials are reshaping America’s urban landscape.

• • •

A few blocks away from the formstone facade row house Jen Horton moved into recently, past the apothecary, a half-dozen vintage shops, a record store, and a new “beer and frites” bar that serves items such as duck poutine and arctic char cassoulet, there is a shop called Bazaar.

“This is one of our favorite stores,” Ms. Horton gushes, as she and her boyfriend, Mark Wingfield, walk past with their dog, Arrow. “It really is bizarre.”

With items for sale such as vintage embalming-fluid bottles, “real prosthetic eye” necklaces, and a Miss Cleo’s tarot card deck, Bazaar reflects the quirky personality that drew Horton and Mr. Wingfield to Baltimore, and to this neighborhood – called Hampden – in particular.

Unlike Gustafson, Wingfield and Horton picked the city intentionally – and separately. Although they met in North Carolina, they began dating only after they had both decided they would move here.

Before they started renting their row house, Horton lived in Washington, where she still works, and Wingfield was in Greensboro, N.C., where he owned a bookstore. When Wingfield decided to sell his business and move elsewhere, he was convinced after several trips to Baltimore to visit friends that the city would be a good place to relocate. Horton also had spent time with friends in the city, and although she enjoyed Washington, she was far more attracted to Baltimore. When she realized that she could take the commuter train to her job at the National Association of Counties, she was thrilled.

“There was something about the overall tone of D.C. versus Baltimore – the feel of Baltimore just worked better for me,” she says. “There was something about it – I can’t even articulate it – but every time I was there I just felt this energy. I loved the art scene. I loved the culture.”

It was also far cheaper. Trading a squeezed apartment in Washington for a full house in funky Hampden, Horton says she has saved $600 to $700 a month in rent and utilities. But she also insists the price tag was only a small part of her decision. It was about finding a place that felt like somewhere: a community of which she could be a part, a place that she wouldn’t just step into to be carried along, like San Francisco or New York, but a place where her life and actions mattered. “I don’t think I had a true sense of place until I moved here,” she says.

All of these qualities – often summed up in the term “authenticity” – are characteristic of Millennial attitudes overall, according to a number of surveys of the population group, which, depending on who is measuring, encompasses people in their teens through their early 30s. Last year, for instance, a Deloitte survey found that Millennials were “eager to make a difference”: Some 63 percent donate to global charities, 43 percent volunteer or are a member of a community organization, and 52 percent have signed petitions. They are also likely to say that they want to be part of something “innovative.” And as the Pew Research Center found in its survey of Millennials last year, the generation is less inclined to be trusting or a part of institutions – whether religious, political, or corporate. All of which makes nontraditional cities attractive.

“A lot of my decision to come here had to do with being in a city where I knew I could make some positive impact,” says Sean Wen, a 25-year-old former Goldman Sachs employee from Texas, who is now another Venture for America fellow working in Baltimore. “Miami and New Orleans – for me those cities were already well established; they already had very positive connotations with them. I wanted Detroit or Baltimore. I thought these cities weren’t getting enough love.”

On a recent rainy evening, Mr. Wen and one of his roommates, 23-year-old Vermont native Forrest Miller, chat about their new city over appetizers at the Hudson Street Stackhouse, one of the neighborhood restaurants within walking distance from their apartment. The pair has been trying food all over the city – good eats, Wen says, is one of his markers of a desirable urban area – and they both approve of the Stackhouse’s laid-back vibe, exposed brick walls, and a menu heavy on burgers (but locally sourced, premium Black Angus ones).

“Cities are volatile. Cities are exciting,” says Mr. Miller, who is working at a biotech company. He says he believes deeply in the Venture for America mission to bring talent to cities where educated young people can make a difference. And he has been taken with Baltimore – its neighborhoods, with their wildly different characteristics; its architecture; the unpretentious ethos, which means that when someone asks what school you went to, they want to know your high school.

“And I like the size,” says Wen. “I am not a huge fan of the gigantic New York City style – it’s an animal that swallows you up. I’m kind of a quaint dude.”

• • •

It is, of course, easy to distort the generational picture.

Although much of what’s written about Millennials focuses on their urban-minded, innovative, can-do-ness (some would also add sense of entitlement and narcissism to the list), by many measures young people in America are struggling. And they are often struggling at home, with their parents, in the suburbs. The Pew Research Center analysis of US Census Bureau data found that in 2012, some 36 percent of the country’s 18-to-31-year-olds – about 21.6 million people – were living with their parents.

This is tied to the high unemployment numbers among Millennials, which the think tank Generation Opportunity calculated recently at 15 percent. Meanwhile, some surveys have found that many young people describe the suburbs as their ideal place to live in the future: A study by Frank N. Magid Associates found 43 percent of Millennials said this, compared with 31 percent of older generations.

Some demographers speculate that student debt and the recent recession, with its housing bubble and resulting financial constraints, are as responsible for the growth of cities, with their available rental properties, as any great shift in public opinion. But others suggest that today’s Millennials, at least the privileged ones, are shaped by a different set of values, which are drawing them to cities such as Baltimore and revitalizing urban areas nationwide.

College graduates of all generations, of course, have tended to move to cities more than other age groups. They are more mobile, more willing to live with roommates, and more inclined to rent than to buy. But the Millennial generation seems even more intent on urban living. Two-thirds of the country’s 25-to-34-year-olds with a bachelor’s degree live in the nation’s 51 largest metropolitan areas. And many of those pick close-in urban neighborhoods, where they are able to walk or take public transportation to work and recreational activities.

“A lot of it has to do with the new urbanist bullet points,” says Joe Cortright, an urban economist who runs the think tank City Observatory and wrote its 2014 report, “The Young and Restless and the Nation’s Cities.” “People want dense, diverse, interesting places that are walkable, bikeable, and transit-served.”

Along with educated young people have come businesses. Scholars talk about how Millennials want to work where they live, and how younger professionals generally shudder at the thought of commuting to an office park in the suburbs. Car culture overall is passé for this demographic: Millennials drive less than other generations, and only two-thirds of 16-to-24-year-olds had driver’s licenses in 2011, the lowest level in about 50 years. So businesses – from small start-ups in Tennessee to the big tech companies in California – are siting offices in urban areas, near their workforces. Twitter and Pinterest, for instance, recently relocated their headquarters from Silicon Valley to San Francisco, primarily to be closer to where their young employees wanted to live.

All this has accelerated a shift already under way in the living patterns of Americans. For the first time in decades, the country’s cities stopped losing their populations around 2010 and began growing.

“There’s no question that this is a relatively good moment for cities,” says Edward Glaeser, a Harvard University economist who is an expert on urban areas. “If you have a half-century perspective – to see where we are now compared to the 1970s is remarkable.”

But, he says, it is easy to get carried away with optimism. Skeptics caution that, as with Millennial migration patterns, economics and the recent housing bust play a significant role in the trend toward urban living. And for all of the Millennial interest in cities such as Baltimore or Detroit, major problems endure. As Mr. Cort-right found in another of City Observatory’s studies, concentrated poverty in many American cities is increasing. School systems are struggling, and unemployment is often far higher than national averages. “Detroit is very far away from Seattle in terms of where those cities are,” Mr. Glaeser says.

Indeed, the Seattles of the country are still attracting far more Millennials than the Detroits and Cincinnatis. New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington, closely followed by San Francisco and Boston, have the largest number of Millennials with bachelor’s degrees, according to Census Bureau data. Arlington, Va., a close-in suburb of Washington, has the highest percentage of Millennials of any US city at nearly 40 percent, according to RealtyTrac, while Washington itself has increased its Millennial population by nearly 30 percent since 2007. New Orleans has also attracted a new flood of 20-to-29-year-olds.

Still, many boosters see the shift in “second tier” cities as a hopeful change. For years, planners across the country have been trying to push growth to areas that already have housing stock, or to what are known as infill areas – places that are undeveloped, but within city limits. These include places such as Baltimore’s Harbor East – a stretch along the waterfront that 20 years ago was a blighted landscape of empty lots and abandoned warehouses, along with a Superfund site. Today it is one of the swankiest neighborhoods in the city, with shiny office and apartment buildings, stores such as Lululemon and Anthropologie, and a new Four Seasons Hotel. (The menu at the Wit & Wisdom tavern there explains that items have been selected as “a thoughtful representation of modern day Baltimore and the future of this city’s culture.” This includes, apparently, Maryland blue crab deviled eggs.)

Successes like this, many say, come from long-held strategic goals and policies – whether tax credits or streamlined building permitting – merging with other factors. Crime in cities is down. Concern about the environment has encouraged some people to pick smaller living spaces. And there are demographic and attitudinal shifts, particularly among those in the Millennial age group.

The Millennials have “seen the peak of suburban sprawl – they want something different,” says Richard Hall, secretary of the Maryland Department of Planning, which has worked on revitalization efforts in Baltimore as well as in other cities across the state. “They see their parents spending a lot of time driving for everything – for work, for education. They see a different path where they are able to more readily take control of their communities, and take an active role in the community.”

• • •

When 30-year-old Matt Pinto was attending Johns Hopkins University in the northern part of Baltimore, everybody knew that the Remington neighborhood, only a few blocks to the south, was a tough area. It had crumbling row houses, warehouses-turned-crack dens, and vacant streets – and few attractions for the college students and young professionals living less than a mile away.

He shakes his head and laughs when asked what he would have thought if he had known his job today would be to manage one of those former crack dens – now a fully rehabbed can factory. On one side, it provides office space for nonprofits. On the other are 40 loft-style apartments, with exposed brick and duct work. Most of the residents in the building are teachers, who get a steep rent discount because of their profession.

Miller’s Court, as the building is called now, is one of two major rehab projects managed by Mr. Pinto, and developed by Baltimore’s Seawall Development Company, that provide nonprofit working space and reduced rents to teachers. With 100 percent occupancy – and a waiting list that reaches some 60 people deep at the beginning of each year – the project has drawn dozens of Millennials to the neighborhood. There is a coffee shop downstairs, and across the street a new restaurant owned by one of Baltimore’s prominent restaurateurs.

“Twenty-Sixth Street was described as the scariest street in Baltimore,” Pinto says, referring to the building’s address. Now, there are people walking through the neighborhood, crime is down, and Remington is considered an up-and-coming place to be.

“I feel like for a while cookie-cutter [living] was a thing,” he says. “Now people want a lot more authenticity – in what they wear, in what they eat, in where they live.”

And it’s simply easier to get “authenticity” here, he and others say, than in cities that are trendier – and pricier. “Charm City, there’s something to it,” he says. “Actually, it’s not really a city if you ask me. It’s a big village.” ρ