NFL domestic violence policy matters to more than just football wives

Loading...

When National Football League owners adopted a new domestic violence policy Wednesday, in a way, it wasn’t just for the wives of football players. It was for Susan Williams, too.

At first blush, Ms. Williams is only tenuously related to the NFL scandal that spawned the changes. She left an abusive relationship more than two decades ago, long before the video of Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice knocking out his then-girlfriend, Janay, turned a spotlight on domestic abuse.

But even for her, what the NFL has done matters. For 20 years, she has blamed herself for the death of a police officer who was killed by her ex-husband and their then-teenage son. She has blamed herself for her failure to rescue her son from the influence of a father who stockpiled weapons in the house as an anti-government survivalist.

She has blamed herself for not leaving the marriage sooner.

Every instance of domestic violence is different, of course. Janay Rice has stood up for Ray (now her husband), saying he made a mistake. She has said he has never abused her before or since.

But the broader conversation spawned by the incident has given Williams a sense of comfort and even courage. The discussion about why abused spouses stay with their partners both frustrated Williams and inspired her to share her own story. She feels the media attention is helping to shed light on the complicated motivations in such cases – creating empathy and pushing authorities to take domestic abuse more seriously.

The situation points to how a repugnant act can sometimes give birth to a positive feedback loop that can help change lives. Publicity is empowering more victims to step forward, and Williams “is a wonderful candidate for someone to say, ‘This is a burden you need to stop carrying,’ ” says Richard Gelles, who has written 24 books on domestic violence.

Mr. Gelles contrasts the reaction to the Rice case to the reaction to the O.J. Simpson case in 1994, in which the ex-NFL star was accused of killing his former wife. “That case actually created a lot of fear in women, that if they left, they would be even more vulnerable,” he says.

That was how Williams, who now lives in San Diego, felt.

“I’m getting so frustrated with people asking why women don’t just leave the situation,” she says. "Sometimes you can't leave, because if you leave he'll burn down your sister's house or he'll kill your aunt…. Domestic violence goes beyond being punched out by a person. It threatens everyone in your life that you love.”

Her former husband, James Oswald, and their son, Ted Oswald, are serving life sentences for a 1994 bank robbery, hostage-taking, and police shooting in Wisconsin. During the trial, she felt that no one cared about her claims of abuse. Since then, she had stayed mostly quiet until contacting this reporter, who had met her during the trial, to tell her story after the Ray Rice scandal broke.

Her story includes a glimpse of what can happen to women trying to leave an abusive relationship. After Williams left her husband, she spent time in a battered women's shelter. “I … saw just incredible poverty among women who had been on the run for ages,” she says. “I was finally able to get away after I’d squirreled away about $300.”

Later, when her ex-husband fled with their three children to another state, Williams had to repeatedly take time off from work while scrambling for money to go and get them.

Studies show the No. 1 predictor of whether a victim will leave or return to an abusive relationship is economic dependency, says Kim Gandy, president and CEO of the National Network to End Domestic Violence in Washington.

“Ninety-five percent of abusive relationships involve financial abuse,” said Ms. Gandy. “He ruins her credit, he runs up debt, forces them to take payday loans, but also, he gets her fired. Once she’s been fired from two or three jobs, what are the chances she’s going to get another job?”

The NFL’s move Wednesday will help.

“If there’s a teachable moment in this, it’s ‘What are workplaces doing?’ ” Gelles says.

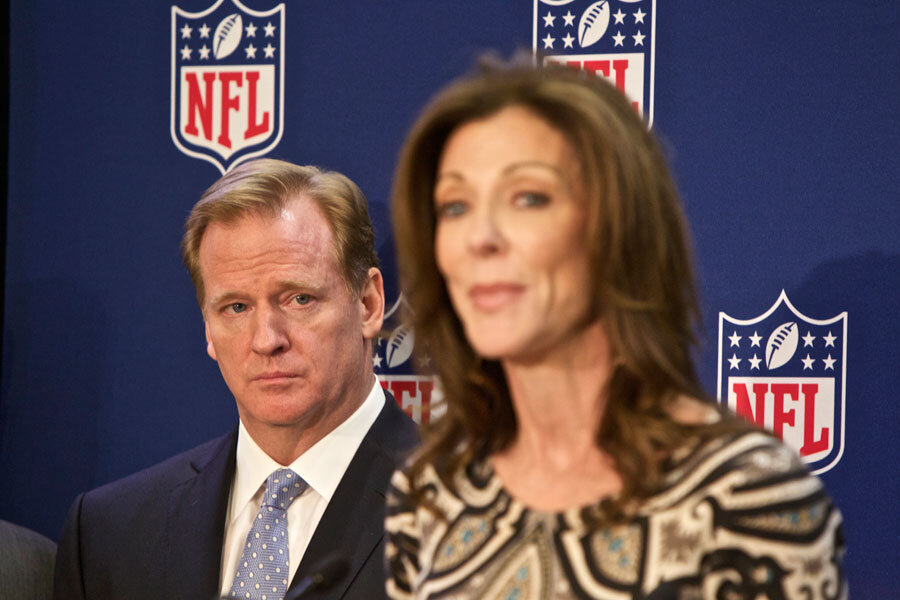

The NFL’s new policy outlines clearer punishments, establishes funds for counseling, expands services for victims and violators, and sets up a new special counsel.

“Is it a question of ‘As the NFL goes, so goes the country?’ Probably not,” says Gelles. “But is it another positive step forward, where a fairly high-profile organization says, ‘This is not going to be tolerated?’ Yes. I think all the other sports leagues will do something similar. Something that men pay attention to has made a statement that this is not acceptable behavior.”

As more women are emboldened to come forward, the stress on shelters and services is likely to become an issue, Gelles adds. After cuts in government funding that “started in earnest” in 2000 and 2001, most shelters are unable to accommodate the increased demand.

Still, Gelles is glad that the Ray Rice case is encouraging victims to get help, especially since attitudes have improved.

“The good news is, we’ve provided a lot more avenues of escape for women – shelters, services, programs, advocates,” he says. “The police and the courts generally take a firmer approach than they did 40 years ago.”

Adds Gelles: “There was a judge in Boston years ago who, when a woman was bringing charges against her husband for battering her, in the course of her testimony she got fairly shrill, and the judge actually leaned over the bench and said to the husband, ‘I guess if I were married to her, I’d have done the same thing.’ And you know, he stayed on the bench.”