Disability is less a barrier to the arts than attitude is

Loading...

| Cambridge, Mass.

“So how many of you all can drive?” Scott Thomas asks a packed theater in Lenox, Mass.

When the audience cheers assent, he deadpans: “Well, I don’t, but I have been a passenger in a car many times, and I’ve seen a lot of bumper stickers ... One said ‘God is my co-pilot.’” He pauses. “I mean, if God’s in the car – let Him drive!” The audience howls, and Mr. Thomas, lips pressed and eyes lowered, waits a beat before diving into his next sequence.

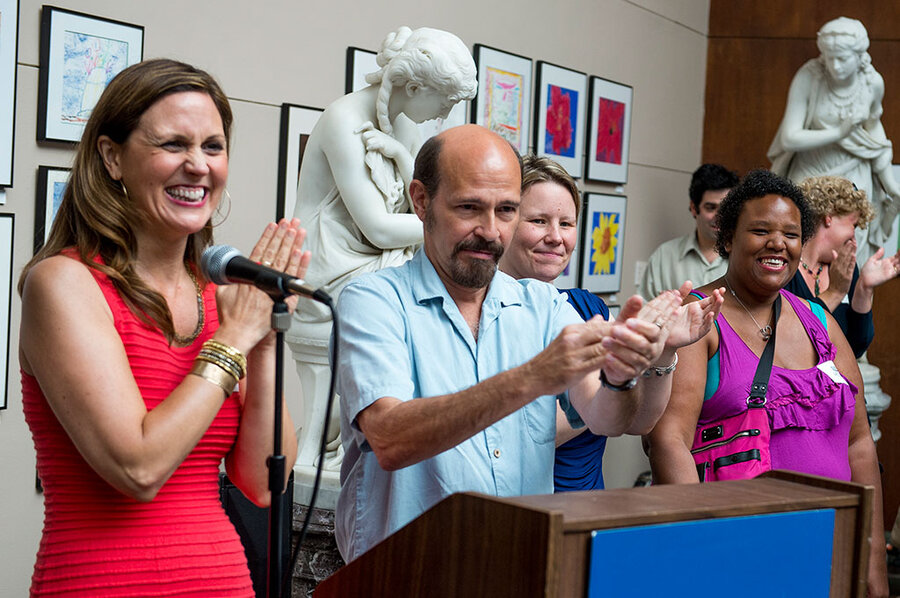

This is Thomas’s stand-up debut. His reluctance to look directly at his audience points to an autism spectrum disorder, but he is connecting with the audience at the Community Access to the Arts annual gala.

CATA, based in Great Barrington, Mass., is one of a growing number of organizations across the country that enable people with disabilities to participate in the enrichment and cultural conversations that the arts offer.

Almost 25 years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, “People with disabilities report that it’s attitudinal [rather than physical] barriers that are actually most challenging in their lives,” says Francesca Rosenberg, director of community and access programs at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Many assume, for example, that the visual arts are only of interest to people with sight, deaf people have no way to appreciate music, or an older person with Alzheimer’s can derive no benefit from a museum experience or an arts workshop. Yet the popularity of specialized tours and descriptive audio guides in museums or the use of performance interpreters to render in sign language the complexities of music show that it is not the disability that keeps people from participating. It is because nobody had thought they wanted or deserved access.

At CATA, which works primarily with people with developmental or cognitive disabilities, Dawn Lane loves that the program “messes with people’s definitions.” Whether attending a CATA art show or the performances at its yearly gala, she says, “people have to recalibrate who they think someone is and what they think they can do.”

At 36 years old, Thomas says he “can’t focus on certain things” and working in groups “was not really for me.” His job in the warehouse of a local retailer is solitary, but at CATA’s poetry and Shakespeare classes, he has found friends and mentors. They were his first audience, and their laughter encouraged him to delight – and surprise – an entire theater.