Smoke jumpers: Firefighters from the sky

Loading...

| Redding, Calif.

Tim Quigley remembers the moment with a bit of horror and, now, some humor. He and two other smoke jumpers had parachuted into a remote section of the Plumas National Forest, in the saw-toothed Sierra Nevada of northern California.

They had worked feverishly to cut a fire line – creating a wide swath of open dirt devoid of leaves, brush, and other fuel – to keep a quarter-acre blaze from mushrooming into a major conflagration. They were just finishing scraping the ground when they heard what sounded like dogs. “Two black bear cubs stuck their heads out from a tree,” says Mr. Quigley.

The mother – ominously – wasn’t far behind. The three men started banging pots and pans. But the bears were hungry and thirsty. They smelled food. “Sure enough the mother ... mock charged us,” says Quigley.

Quivering, they started to slowly back down the hill so they wouldn’t agitate the bears. The three men got separated. Moments later, his adrenaline flowing, his senses heightened, Quigley heard what sounded like another bear coming from the other direction. He clambered up into the “wee branches of a tall tree.”

Down the hill came ... a smoke jumper from a nearby fire.

“Getting treed by another smoke jumper – I didn’t live that one down for a few years,” says Quigley.

The moment, still vivid in his mind 22 years later, is a reminder that being one of the nation’s elite firefighters isn’t like being a mailroom clerk or concierge. It’s dirty. It’s dangerous. It’s strenuous. And you probably should know how to climb a tree for those moments when it isn’t a colleague sauntering down the path.

Yet you probably wouldn’t know that from just talking to some of America’s smoke jumpers. As the United States struggles with another historically bad wildfire season, I’ve decided to travel to Redding, Calif., one of nine smoke-jumping bases scattered across the West, to see who these people are, what impels them to parachute into forests that have turned into furnaces, and how fighting such fires has changed in the 74 years since the corps was formed.

I’m using Quigley as my lens into the fraternity, which only seems appropriate: He has 700 jumps – the third-most in history; 286 of those are fire jumps (also one of the highest numbers of all time) and the rest are practice jumps. Until he retired recently, he had been dropping into fire zones for 36 years, since Jimmy Carter wore a cardigan in the White House.

The first thing that struck me about Quigley is what he isn’t. He’s not a Chuck Yeager. He is not a puffy-chested cowboy, end-zone-dancing football player, or alpha male. He is meek first, bold second, and always self-effacing. He is basically shy and doesn’t think of himself as doing anything special. It is hard to even get him to talk about himself. And this is typical of many of my other interviews with smoke jumpers, modest and quiet all.

They are, in a way, American antiheroes.

“Risk-takers and thrill-seekers don’t fit in,” says Bob Bente, head of training at the base here in Redding. “We don’t want anyone out there jeopardizing any facet of the operation. We treasure the kind of calm, focused attitude that Tim has been able to model for our rookies. It’s innate, but some of it can be taught.”

Mitch Hokanson, a 15-year smoke jumper from Happy Camp, Calif., who carves sculptures with a chain saw during his downtime, puts it another way. “Smoke jumpers are completely ordinary people who you would never notice in any other way. The only difference is that we jump out of airplanes.”

• • •

I first meet Quigley outside the “loft room” at the Redding base, which sits in an area once known as Poverty Flats for the bad fortune of its inhabitants during the California gold rush. The loft is a warehouse-sized room filled with long tables big enough to stretch out parachutes for rigging.

And it turns out that when smoke jumpers aren’t descending through cauliflower clouds of smoke, they spend a lot of time sewing.

“Some of these guys get so fast and good at this that I would put them up against any worker in a garment factory,” says Quigley of the jumpers’ ability to stitch patches on parachutes.

Rows of sewing machines sit beside the tables. Along one wall, dynamic photos show smoke jumpers leaping out of planes, floating down, and fighting blazes. Some of them are class photos, giving the wall the look of a yearbook.

“There I am in a much younger incarnation,” Quigley says, pointing to a kneeling figure in a 1979 photo, his first year. He looks indistinguishable from Brad Pitt. I make the comparison. Quigley laughs it off. “Maybe some other kind of Pitt,” he says. The longer hair of his youth has given over to a military buzz cut.

Other smoke jumpers here – there are about 40 in all – are pacing the tarmac outside and closely monitoring the weather reports on a flat-screen TV for any signs of lightning, the match of Western forest fires.

They have to be ready to move quickly. Smoke jumpers are America’s human fire extinguishers. Their job is to parachute into places inaccessible by road or trail and douse fires before they get out of control. They are not the main force that fights wildland fires in the West. That’s left to the more than 10,000 crew members who work for the US Forest Service, the US Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Land Management, and other federal and state agencies.

Only 400 smoke jumpers exist nationwide. When they do their job right, you never hear about them.

“I told my mom, you are never going to see me on TV,” says rookie smoke jumper Brian Janes, who worked his way up from other firefighting jobs to what he considers the pinnacle of the profession. “These are mostly tiny little fires of a half acre or less. Most will be put out in a day and a half or less.”

The smoke jumpers usually parachute from 1,500 to 3,000 feet into the safest spot near a fire. They float down from the sky like Mary Poppins. They wear special Kevlar suits with Elizabethan collars and helmets with wire mesh on the front. They stuff their pockets with ropes, rappelling equipment, and – sometimes, surreptitiously – snacks, from energy bars to beef jerky. On most missions, two to eight smoke jumpers are dropped, but more can be summoned.

Once on the ground, they start creating firebreaks using Pulaskis (tools that are half ax, half adz), shovels, and chain saws. Most of the blazes they battle are extinguished or turned over to other firefighters within three days, but crews have been known to spend more than a month in the field.

“We’re such a small group and are in and out so quickly that [people] think we’re like Bigfoot – or ghosts,” says Luis Gomez, another smoke jumper. “They hear about us but never see us.”

What draws many people to the job is a sense of adventure. But there’s also the physical challenge, the unpredictability, and a feeling of service.

“One thing I really like about this job,” says Quigley, “is that you may be having an entirely ordinary morning packing boxes at the base, and by midafternoon, you are anywhere from Idaho to Alaska leaping into the air.”

Many smoke jumpers have fire in their blood: They have followed a friend or family member into the profession. Indeed, the fraternity of smoke jumpers is small enough that the secrets of and fascination with the profession are often passed from generation to generation, adding to the mystique of the job.

I catch up with Doug Powell, an eight-year veteran, outside the loft room. He’s a gregarious man with a Bunyanesque build, not unlike many of the smoke jumpers here who spend a lot of time running, doing sit-ups and push-ups, and lifting weights. He grew up with a father who was a fire lookout for the US Forest Service in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest not far from Redding.

“We would visit my dad up on the peak and watch jumpers leaping into the gnarly terrain, and hear the chain saws and watch the smoke dissipate,” he says. “It was awesome. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

It took him a while. He applied for a smoke jumper job after becoming a regular firefighter for a season and was told he needed more experience. He took a college course on firefighting and then joined a hotshot crew (a team trained to fight big fires but which doesn’t parachute) for two years. He’s been a smoke jumper for eight years.

“It’s still amazing to me that we get paid to parachute,” adds Mr. Hokanson, a father of four. “We get to travel a lot, to really pristine areas, away from roads, up on ridges with good views. We get to see a lot of the country, fly around with the airplane doors open. It’s great to share this kind of adventure with a very diverse group of guys who have common interests.”

Hokanson’s children are captivated by what he does, too. They visit the base, sit in one of the planes, and pretend they are parachuting into fires.

“Even though they have come a hundred times, they still love it,” he says. “If I ask them what they want to be when they grow up, it’s ‘smoke jumper’ – although I expect that will change.”

It might not be easy for them to follow in their father’s boot steps. Smoke-jumping is a coveted job. Some 1,000 people apply for about 20 openings a year. Only 14 of the country’s smoke jumpers are women. Unlike in the past, many people are staying in the profession longer now. “In the 1940s and ’50s, it was more typical for a smoke jumper to come and put in two to three years,” says Mr. Gomez. “Now they are staying in for decades.”

The rigors of the job limit who can do it – and sometimes cut careers short. Chuck Sheley was a smoke jumper for 11 years, until he retired in 1970, after his 11th surgery.

“You’re jumping into 150-foot trees and rocks,” says Mr. Sheley, who is now editor of Smokejumper Magazine. “It’s rugged. You’re carrying 100 pounds of gear. When you’re 25, you can jump, land hard, and keep on going. Years later you realize it’s why your rotator cuff is gone.”

• • •

Billowing fists of white clouds hover over Lassen Peak, the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range, 50 miles to the east. I’m riding in a car with Quigley, who seems to instinctively scan the skies even though his official jumping days are over. Like any good smoke jumper, he’s one part firefighter, one part meteorologist.

“All our eyes are on that thunder cell as a possible lightning burst,” he says. “When it comes, we go.”

It’s 104 degrees outside. California is as dry as flint. Dry lightning is a common villain. But in the hot summer months, even when it rains, many droplets don’t make it to the earth. They evaporate on the way down. Danger lurks in every thunderhead.

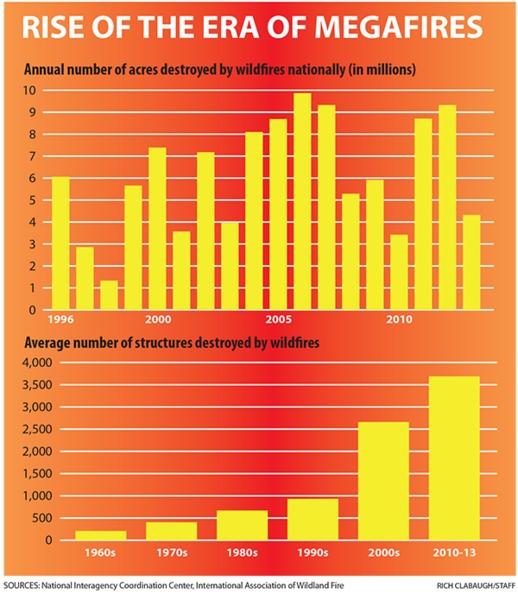

This is what Quigley and his comrades who fall from the skies have had to confront the past decade: a new era of megafires. People who study forest fires say that the past 10 years have brought increasingly frequent blazes that burn 500,000 acres or more – 10 times the size of ones 20 years ago.

Several factors have contributed to this trend. One is climate change, which has been marked by a small but significant increase in the average yearly temperature across the West. Second is a fire season that is now nearly year-round. Third is the encroachment of homes into wooded areas. This has coincided with a rise in hiking, cycling, and other recreational use of wilderness areas.

In 2012, Colorado’s Waldo Canyon fire alone burned more than 340 homes and displaced 32,000 people. It broke a state record for the most homes burned that had been set just a few days earlier when the High Park fire destroyed more than 250 homes. The next year brought the Black Forest fire, which consumed more than 486 houses.

This year hasn’t been much more forgiving. Through Aug. 20, more than 2.6 million acres of land have been burned in wildland fires across the country – down from the epic years of 2011 and 2012, when more than 6.5 million acres had been charred by this time, but still bad nonetheless.

Underlying the increase in huge fires has been a century-long policy of the US Forest Service to suppress wildfires as quickly as possible. The unintentional consequence is less natural eradication of underbrush, now the primary fuel for huge fires. As such, some argue that the whole profession of smoke-jumping – at least the tactic of extinguishing fires immediately – needs to be reexamined.

“Jumpers specialize in suppressing backcountry fires, exactly the kind of fires that we need more of,” says Stephen Pyne, a professor of life sciences at Arizona State University in Tempe who is just completing two books on the past 50 years of American fire management. He says the American firefighting community spent a half century trying to convince the US public that forest fires should be put out right away, in all cases.

Now, he and others argue, it might be time to let naturally occurring fires do the work that experts say they are meant to do: thinning out undergrowth to prevent the larger, deadlier, and costlier mega-blazes that increasingly have ravaged the American West.

Deciding policy is above the paygrade of these firefighters, of course, and if the winds of strategy and tactics change, the smoke jumpers will, too. Quigley, for one, says smoke jumpers have all seen fires that were doing more good than harm. “Many fires will burn beneficially for days and weeks, but usually at some point the weather and fuel conditions change to where it gets up and goes big,” he says.

Translation: The fire starts to get out of control. Or it imperils houses and people. How do you let that burn?

“Most of the fires we get involved in, the public is no longer in the area,” he says. “But with more people living out in the woods, smoke jumpers along with other firefighters will be saving more homes and lives.”

• • •

While smoke jumpers may be loath to say they do anything heroic, one who isn’t so modest about their exploits is Becky Quigley, Tim’s wife. The Quigleys live in a modest ranch-style house on the outskirts of Redding, in a tidy neighborhood of boxwoods and kids on bicycles.

I meet with Becky around their front room coffee table. I want to talk to her in part because it’s difficult to get Tim to tell stories about his work that don’t make him sound as if he is just a roofer. Becky doesn’t disappoint.

In her early adult years, she worked as a flight attendant for Sierra Pacific Airlines in Tucson, which transported a lot of smoke jumpers. After she turned Tim down for a first date, they ended up going out twice, and, apparently seeing the Brad Pitt resemblance that he doesn’t, she told a friend: “Mark my words, I will marry that man and have his babies.”

One daughter, Laney, was born in early June and thus endured the absence of her father for her birthday every year but five growing up. Summer was always fire season and Tim was out on the lines, somewhere between Idaho and Alaska, digging trenches.

“I always remember knowing that what he did was very important and took a lot of guts to do,” says Laney. “I mean, jumping out of an airplane to fight forest fires isn’t for the faint of heart.”

Becky says that being married to Tim, at least in the summer, was like being a single mom. But she notes that he was always good about informing her where he was and what he was doing day by day – all in the pre-cellphone era. And once he was home, he was home: No stories of fire exploits. No complaining about work.

“I loved when he came home,” says Laney. “I remember him smelling of smoke and fire and to this day, it is one of my favorite scents and takes me right back to those summer days.”

The family did, however, endure a few restless nights. In the summer of 1994, the South Canyon fire on Storm King Mountain near Glenwood Springs, Colo., took the lives of 14 firefighters. Becky followed the news nervously on the radio. She called the base numerous times asking if he was OK, only to be told, “I don’t know.” Finally, Tim was located, safe.

After that experience, Becky made a decision. She told the base secretary that she didn’t want to be informed of Tim’s death like the mother was in “Saving Private Ryan,” with a knock on the door by some chaplain or base official. But instinctively she felt Tim was experienced and cautious enough to minimize the dangers.

“I knew he was too smart and too good to allow himself to get into any bad situations,” she says.

When he did confront danger, she wouldn’t hear about it. After one outing he returned bruised from his knee to his hip. She only found out about it after he took off his pants. Tim says – almost inconceivably – that it was the only time he had been injured in his 36-year career, until 2013 when he hurt his knee and was taken off the jump list for the first time.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t other scary moments, though. Mr. Powell tells the story of another bear. He, Quigley, and two other smoke jumpers – one a rookie – were camping outside a cabin in 2011 in Alaska, where they had been sent to prepare for an approaching fire. Their cooking fish and keeping other food outside had brought a grizzly to within 40 feet of the camp.

Three of them climbed up on the roof of the cabin. As they huddled, they realized the fourth man, the rookie, was still in his tent. He hadn’t seen the bear and was sure the whole incident was a hoax – part of an initiation. One of the men saw a chain saw by the cabin door, jumped down, fired it up, and charged the bear, scaring it off.

After spending time with Quigley, I get the feeling that if he hadn’t hit the mandatory retirement age of 57, he’d still be jumping out of planes and running into the occasional bear. Smoke-jumping has always just seemed to be in his DNA.

As Becky puts it, with one last story: “His mom saved the first kindergarten picture he ever drew. It was a forest fire. Basically a bunch of brown trees burning with great swatches of red and yellow crayon scribbles.” ρ