Post-Casey Kasem, what is 'Top 40' music, exactly?

Loading...

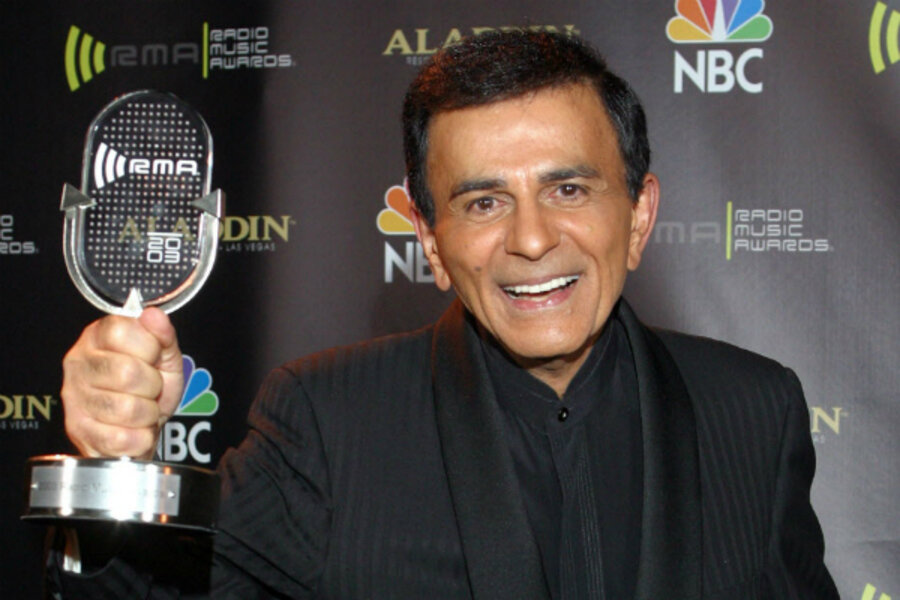

Legendary broadcaster Casey Kasem tabulated hit songs and played them every week to Americans from “coast to coast.” The winners and losers that climbed up and fell from his weekly countdown presented a portrait of Americans unified by pop music; for many years, it was a reliable way to assess mass tastes.

However, as Mr. Kasem’s time before the microphone dwindled, the format he created to determine pop music popularity became less relevant. With the splintering of radio formats, followed by the advent of digital media, it became more of a challenge to quantify hit songs, no less figure out what American consumers, as a collective, were listening to together and at once.

“The notion of a ‘No. 1 record’ began to be outmoded even with the rise of FM Radio in the 1960s, which became the cutting edge music on radio,” says Paul Levinson, professor of media studies at Fordham University in New York City.

“Nowadays, with streaming on Spotify and downloads on iTunes and a dozen other places setting the standard for what is the most popular recording, the impact of commercial radio play is fading,” he adds. “A new kind of chart, based on all of these Internet factors, is needed.”

Kasem died Sunday in Gig Harbor, Wash., according to the Associated Press. “American Top 40,” the show he hosted for a total of 24 years is now handled by “American Idol” host Ryan Seacrest.

A former deejay in Flint, Mich., Kasem launched “American Top 40” in 1970, a time when commercial FM radio was entering its glory years. At that time, Kasem relied on data from the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, which weighed its rankings based on songs played on jukeboxes, radio play, and sales at brick-and-mortar stores. That since has changed to reflect changing times: Billboard now constructs its chart using Nielsen SoundScan sales data, both at retail and digital outlets, as well as radio play and streaming services like Spotify and Pandora.

At the start of Kasem’s show, the chart was problematic in that it favored only the sales of commercial singles, which meant it weighed heavily in favor of pop artists, and not those who concentrated on full albums.

That created a distortion since many of the best-selling artists at the time, who dominated the emerging FM radio format, were rock groups like Yes, Pink Floyd, and Led Zeppelin, all of whom were considered “album-oriented” artists. That meant that a band like Led Zeppelin might have an album at, or near, the top of the charts, but would rarely make the Top 10 of Kasem’s countdown.

According to “The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, Ninth Edition” by Joel Whitburn, the problem continued up until Dec. 5, 1998, when Billboard revised the Hot 100 to include songs that were not commercially available as singles. As radio formats became more segmented in terms of genre, the magazine followed suit, creating separate charts for a range of musical tastes such as dance, hard rock, country, and more.

But by that time, Kasem had switched to a new way to assess the hits: Mediabase, a service that monitors radio play in nearly 200 North American markets. However, by the 1990s, the digital era transformed how consumers accessed music. Today, it is downloaded and streamed on smartphones, tablets, and via automobile dashboards, in addition to home entertainment systems. The revolution has created a chaotic marketplace of new services, from Shazam to Amazon to SiriusXM, vying for listener ears.

Listeners now exist in a niche world of culture and enjoy the freedom to curate their own tastes without the guiding hand of radio programmers. That's why megahits are no longer quite as mega as in Kasem’s time.

“The problem of identifying ‘No. 1’ songs has certainly become more complex in recent years. No longer can a charting organization look to one or just a few types of sources to calculate a song’s success,” says Ed Arke, a communications professor at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pa.

Even what constitutes a hit is now elusive: Social media buzz can catapult a song like the 2013 hit “Harlem Shake” by Baauer to instant mass attention and skyrocketing download sales without outside exposure, for example. Viral popularity based on views and not retail sales is often difficult to assess, but it has not gone unnoticed, which is why Nielsen Soundscan now tracks major streaming services.

“What we’re seeing is more artists who are having small to medium success and fewer megahits, a trend likely to continue because the number of sources to factor into such a rating systems have grown so much, it is becoming increasing more difficult to gather all of the relevant data from across the country and around the world,” Professor Arke says.

Even the world of countdown shows has multiplied since Kasem departed the airwave. In addition to Seacrest’s “American Top 40,” other countdown shows exist on SiriusXM, CMT, VH1, Last.fm, Hype Machine, among other outlets – many based on different metrics and showcasing different results.