Immigration: Assimilation and the measure of an American

Loading...

If there were such a thing as a classic American immigrant story, it might sound something like the one Arlene tells of her family.

Her immigrant parents each arrived in New York City poor but eager, searching for a better way of life. They found work – and each other – in the garment district; they married, had children, and sent their girls to parochial school where nuns taught proper English.

Arlene's parents told her and her sister that here, in the United States of America, they could do anything. So the girls went to college, became professionals, married, and had children of their own – English-speaking children who would never consider themselves anything but American.

It is a familiar, almost nostalgic, narrative; one that evokes sepia-toned photos of Ellis Island, Little Italy boccie players, German grandmas, or Eastern European deli proprietors.

But there is a twist.

Arlene's last name is Garcia. Her parents came from the Caribbean, not Europe. Today she lives in Lawrence, Mass., a city north of Boston that is more than 73 percent Hispanic. She is fluent in Spanish and English, switching seamlessly one recent morning at work answering the phone at Esperanza Academy, a tuition-free, private school for low-income girls. She is married to a Dominican man (albeit one whose name – Johnny Mackenzie – is far more gringo than hers) and returns regularly to the Dominican Republic (although these days she far prefers the Punta Cana resort area to the villages of her ancestors).

Is she assimilated? She laughs at the question: "Well, it depends on what you mean by 'assimilated.' "

That, it turns out, is a controversial question. And it is one that has moved in recent months to the forefront of public debate, as lawmakers wrestle with immigration reform, and as the Boston Marathon bombings – allegedly perpetrated by two ethnic Chechen immigrants – ushered in a new wave of speculation about newcomers' ability, or desire, to integrate into American culture.

On one side are conservative officials and pundits who worry that a flood of Spanish-speaking immigrants and a reverence for "multiculturalism" have led to a population of immigrants in the US unappreciative of and unconnected to their new country. On the other are a slew of academics, armed with studies from think tanks and longitudinal research projects, who say that assimilation these days is as strong as it has ever been, that immigrants as a group are still more enthusiastic about the country than the native born, that immigrants' children tend to do better than their parents by a host of socioeconomic indicators, and that within three generations an immigrant family fully identifies as American.

This happens across the country, they say, even in regions such as the Southeast that are not traditional immigrant destinations.

Although there has been bipartisan support in Congress's immigration reform efforts for provisions to better integrate new immigrants into US civic and cultural life, as Arlene Garcia and her family show, the notion of assimilation – or "integration," "incorporation," or any word used to describe the process of belonging – is far from straightforward. To evaluate how and whether immigrants – and, arguably more important, their children – are becoming part of this country involves questions of identity, belonging, and the very essence of being American.

Can you measure assimilation?

In 2006, Jacob Vigdor, a professor of public policy at Duke University in Durham, N.C., joined a group of academics in a series of meetings convened by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

The scholars, all with backgrounds in immigration research, were focused on a single question: Is there a way, in the face of an increasingly emotional debate over immigrants in the US, to actually measure assimilation?

This is no simple question. The 2010 US Census found close to 40 million immigrants in the US, making up 13 percent of the population. In 2012, the census determined that 36 million more were "second-generation immigrants," or the American-born children of immigrants. And while much of the public discourse focuses on Latinos – particularly the estimated 11.5 million here illegally – the portrait of America's foreign born is far more diverse.

The country is in the midst of what most scholars refer to as the "modern wave" of immigration, which started when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This law essentially opened the door to Latin Americans, Africans, and Asians who had previously been barred by an immigration quota system that gave preference to northern Europeans. Since then, 40 million immigrants have come to the US, reports the Pew Research Center.

In sheer numbers there are more immigrants today than in prior generations, but as a percentage of the population, first- and second-generation immigrants peaked in the early part of the 20th century. In 1900, 34.5 percent of the US population was first or second generation; last year it was 24.5 percent.

Today, census data show, 12 million immigrants come from Mexico and 10 million hail from South and East Asia. Almost 4 million come from the Caribbean, while 14.5 million come from Central America, South America, the Middle East, and elsewhere. Within those groups, of course, there are huge differences; that "elsewhere" category, for instance, includes hundreds of thousands from countries ranging from the United Kingdom to Nigeria to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Categorizing the assimilation of all these different people, Professor Vigdor and the others knew, could prove a daunting task. Even the word itself – "assimilation" – had become contentious; in academia it was associated with nativist pressures on newcomers to assume Anglo sensibilities at the expense of their own culture and history.

But as a social scientist, Vigdor was eager to find evidence in an emotion-laden debate. The key, he says, is in census data.

"When you talk to some people about immigration today, they say, 'Well, my grandmother came here in 1902, and she learned to speak English, and she did all these things, and the immigrants today aren't doing it,' " Vigdor says. "And as it turns out, we were able to get a good sense of whether all the grandmas were really like that."

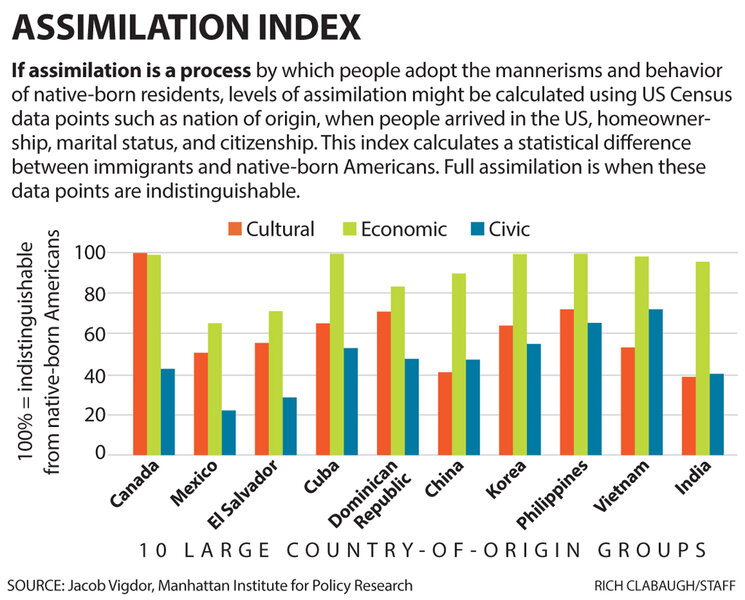

As early as 1900, the US Census was asking people about where they were born and when they had arrived in the US. Using these markers, as well as other data points such as homeownership, marital status, and citizenship, Vigdor created an index that calculated a statistical difference between immigrants and native-born Americans. Full assimilation, according to Vigdor's work, is when these data points are indistinguishable.

"Assimilation is a process whereby people come to adopt the various mannerisms and behavior of native-born residents of a country...," Vigdor says. "By being able to track immigrants as they spend more time in the US, we can trace out how that process works. And the process actually works in a remarkably similar manner whether you're looking over the past 20 years in the US or looking at immigration from Eastern Europe at the turn of the last century."

In other words, a first-generation immigrant will usually struggle with more cultural differences than his American-born child, who will grapple with more cultural disconnect than his children.

But there are also significant differences between immigrant groups, he points out, more so than between immigrants overall and the native-born population.

In his work, he developed three categories of assimilation – civic, cultural, and economic – and then combined those categories for an overall assimilation score. By his findings, Latino immigrants tend to be least assimilated, particularly on measures of civic and economic assimilation, which include characteristics such as citizenship, professional status, and homeownership.

Indians and South Koreans score higher on economic assimilation than on cultural assimilation index measures, which include questions about language, marital status, and the number of children in the adult's household.

He has also found that, as a whole, immigrants to the US assimilate far more than those in European countries, but do so less easily than immigrants in Canada.

"It turns out that almost every developed country has worries about immigration," he says. In Europe, immigrants "have a harder time working their way to citizenship [and] immigrant unemployment problems are more acute.... Even if you look at a basic thing like homeownership – the home-ownership rate for immigrants in most countries is lower than for natives. The disparities in European countries are much more acute than in the US."

In his most recent index, this year, Vigdor found that immigrants to the US today were more assimilated than at any time in the past decade. He attributes this primarily to demographic shifts in post-recession America – new Mexican migrants, who typically score lower on his index, are down in numbers; while Asian migrants, who tend to be from a higher socioeconomic level and score higher on his assimilation index, have increased.

Scholars such as Richard Alba, a sociology professor with the City University of New York who has written extensively on immigration, are more than a little skeptical.

Professor Alba says he is wary of indices of assimilation, which he sees as too simplistic to capture the full complexity and nuance of social integration.

"They might be useful, but they don't exhaust the concept of assimilation," he says. "To take a simple example: We want to know whether people feel like they belong in the United States. How much do they identify with the United States?"

To get at this more important marker of assimilation, Alba says, you need to find out how immigrants feel. Which is what the Pew Research Center has tried to do in a number of recent studies.

Questioning a 'patriotism gap'

In a survey report released earlier this year on second-generation immigrants, who many scholars say are the true markers of a family's assimilation or lack thereof, Pew found that the children of immigrants are, in general, doing better economically than their parents, are more likely to marry and have friends outside their ethnic groups, and are twice as likely to say they consider themselves to be a "typical American." (Six in 10 Hispanic and Asian-American second-generation immigrants respond this way.)

Meanwhile, second-generation Hispanics and Asian-Americans "place more importance than does the general public on hard work and career success," the Pew research found; they and their parents are more likely than the native-born population – and even more likely than the older adult children of European immigrants from the turn of the last century – to feel optimistic about the direction of the country. More than 80 percent of second-generation Hispanics and Asian-Americans say they can speak English "very well"; 10 percent say they can speak it "well."

"There is a lot of that very positive data in that second generation report," says Paul Taylor, executive vice president of the Pew Research Center. "When you look at values, sense of belonging, things are unfolding the way that a society that opens its arms to immigrants would want it to unfold. Is everything perfect? Of course not. But there is a lot of positive news in that data."

There are other reports about immigrants' feelings, however, that come to a different conclusion. A week before the Boston Marathon bombings, the Hudson Institute, which generally researches conservative issues, released a report claiming a "patriotism gap" between the foreign- and native-born.

Citing a new quantitative analysis of Harris Interactive survey data, the Hudson Institute's researchers determined that native-born citizens are, by 21 percentage points (65 percent to 44 percent), more likely than naturalized immigrants to view America as "better" than other countries rather than "no better, no worse." When given a choice, the native born are more likely to describe themselves as "American" rather than "citizen of the world"; 67 percent of the native born believe the US Constitution is a higher legal authority for Americans than international law, as compared with 37 percent of naturalized immigrants.

These statistics led the researchers to conclude that "America's patriotic assimilation system is broken."

A number of conservative columnists jumped on this finding, seeing proof in news reports that at least one of the Tsarnaev brothers, accused of the Marathon bombings, had felt alienated in and angry at the US.

All of which gets at a bigger issue when it comes to analyzing cultural integration: Who gets to describe the values of a "typical American?"

As Alba points out, a "typical American" changes region to region, family to family. The meaning also changes based on socioeconomic surroundings.

In the 1990s, Princeton University's Alejandro Portes, considered one of the leading thinkers on immigrant integration, helped develop a theory of "segmented assimilation," which at a basic level says that because American society is so unequal, there are a number of social places where an immigrant can fit – including the social underclass.

Often referred to as "downward assimilation," this is when people join gangs and adopt a street culture that is quite American, but not the sort of American that the Hudson Institute had in mind.

Indeed, the pressure for the sort of assimilation described by the Hudson Institute can often backfire, Professor Portes says. (He also takes issue with the word "assimilation," preferring "integration" or "incorporation.")

"Nativists take the position that they don't want any immigrants at all – they want to build fences," Portes says. "The other position is to turn [immigrants] into Americans as quickly as possible – this is forced assimilation.... The problem is that the first generation cannot be turned into Americans instantly. And the attempt to do so is often counterproductive. It creates fear and alienation, it denigrates the culture and language of immigrants themselves, and it denigrates it to their kids."

Not only does this put the country as a whole at a disadvantage – after all, Portes says, with the global economy, citizens should understand multiple languages and cultures – it also puts children at the risk of downward assimilation because it hurts their relationship with their parents.

"The idea that the habits and foodways and the religious patterns of immigrants are not worth it and should be eliminated – that is counterproductive," he says. "In the history of this country, groups like Italians and Germans and Poles gradually developed a phased integration into American society. And today, elements of immigrant culture – the Irish, the Italian – are celebrated as positive parts of American culture."

'It's the texture'

In Ms. Garcia's household, there is a regular debate over sleepovers. Her Dominican-born husband cannot, for the life of him, understand why their 14-year-old daughter would want to stay at someone else's house for the night. This is not atypical, she said. Dominicans, and many other Latinos, just don't do sleepovers.

"He'll say, 'You have a perfectly good bed here!'" Garcia says, laughing. "I'll say, 'Johnny, just let her be.' And then he'll say, 'You know, if there's a fire, you know they're not going to be worried about Marleyna. Oh no. They're going to get their own child first.' I'm like, 'Oh my goodness, can you be any more dramatic?' But then I'm awake all night thinking about fires."

She laughs again. It's a far cry from the assimilation debates in her childhood, when the nuns insisted to her father that they speak English at home.

"He said, with that accent of his, 'Seester, out of the home, you da boss,'" Garcia recalls. " 'Inside of the home, I dee boss. But I promise you, she will learn to speak good English. But she will also learn to speak our language.' "

Now she worries that her own daughter doesn't know enough Spanish to talk with her cousins.

"But this is what's so wonderful about this country," she says with a smile. "It's the texture. The stories."