Supersize America: Whose job to fight obesity?

Loading...

| Los Angeles

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg is the latest elected official to seek to use the power of government to slim down Americans' waistlines. But he's hardly the first.

Before he raised eyebrows by proposing to ban the sale of sugary sodas bigger than 16 ounces at New York's restaurants, delis, cinemas, and stadiums, officials elsewhere have tried other strategies for fighting the obesity war. They've enforced moratoriums on new fast-food outlets in certain neighborhoods. They've required eateries to print calorie counts of menu items, and they've kicked sodas and snack foods out of public schools.

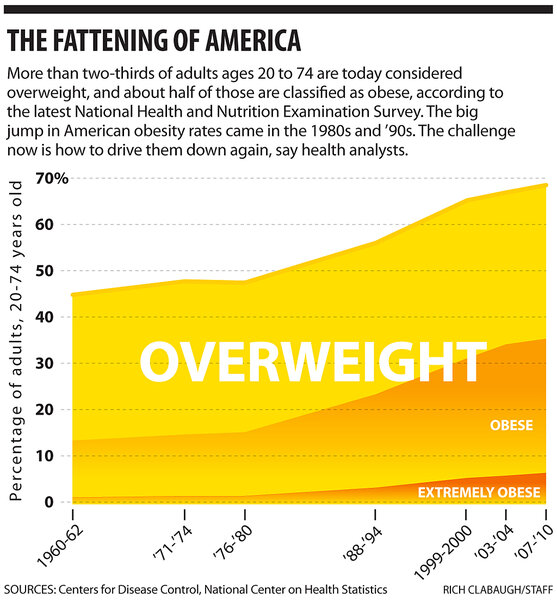

The sharp rise in obesity rates that marked the 1980s and '90s has flattened in recent years, but researchers disagree over how much difference such government interventions have made. The result is that policy proposals like Mr. Bloomberg's tend to be greeted by equal parts cheers and jeers – with many public-health activists giving them the benefit of the doubt, and many restaurateurs and food purveyors slamming such intercessions as "nanny state" limits on individual choice.

In between is the US public, collectively heavier than ever, trying to sort out for themselves whether public-health liabilities that officials attribute to obesity warrant intrusion into a behavior as private as eating and drinking.

One is Angela Hutchinson, a casting director and, on this day, a patron at McDonald's in Sherman Oaks, Calif. Here, calories are printed on the menu for all to see, courtesy of a state law that since 2010 has applied to restaurant chains. Ms. Hutchinson says she routinely checks the calorie count when she eats out, but not here.

"Gimme a break. This is fast food," she says, ordering a Big Mac and fries. "But when I'm sitting down, I really do use them and appreciate them."

Those who say obesity is the public's business note that it has a greater effect on the prevalence of chronic illness and on rising medical expenditures than does heavy smoking or problem drinking. In 2008, obesity-related conditions accounted for nearly 10 percent of total US medical costs, or $147 billion, with taxpayer-borne Medicare and Medicaid assuming a large part of the burden. Indeed, the medical costs paid by third-party payers for people who are obese were $1,429 higher that year than for people of normal weight, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which tracks public-health issues.

Rising rates of obesity in the United States have been documented for at least 20 years now. Almost 38 percent of today's adults and about 17 percent of kids ages 2 to 19 are considered obese, meaning excess body fat has accumulated to the extent that health could be adversely affected, according to the CDC.

Few quibble over the scope of the problem or its possible consequences – only over how best to tackle it. Most see public education as an appropriate role for government, akin to first lady Michelle Obama's "Let's Move" campaign that urges kids to exercise and to choose fewer "empty-calorie" foods. But some draw the line at regulations or specific prescriptions from officialdom.

Take the recent flap over the proposed ban on supersized sugary drinks, which would actually limit people's choices.

To Harold Goldstein, the evidence in favor of such a ban is clear and convincing, especially for K-12 public schools.

"The science on the relationship between soda and obesity is unequivocal," says Dr. Goldstein, executive director of the California Center for Public Health Advocacy (CCPHA).

A University of California study commissioned by CCPHA showed that the average American in 2001 consumed 278 more calories a day than in 1977 – with 43 percent of that increase coming from soda and other sugary drinks. Goldstein pairs that finding with another study, just out, showing that since California in 2005 banned the sale of soda and "junk food" on campuses of K-12 public schools, students there consume 170 fewer calories per day than do students living in states that still sell those products at school.

"Public policies that limit the marketing of sugary drinks are likely to be the single most important strategy for curbing the obesity epidemic in this country," he says.

But to others, the benefits of a ban on extra-large sugary drinks – or even slapping a tax on them – are not so cut and dried.

Research shows that consumption of soda, like consumption of cigarettes, shrinks in the face of a significant tax placed on it, says Elizabeth Vestal, policy analyst with the Schroeder Center for Health Policy at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Va. "However, careful studies have found that the actual effects of this consumption reduction on obesity are less clear," she says in an e-mail. "This is partly because consumers substitute higher-priced soda with other caloric beverages."

[Editor's Note: The original version of this story misattributed the quotations of Elizabeth Vestal to another expert at the Schroeder Center for Health Policy.]

And then there's the matter of fairness. Why single out soda and not, say, doughnuts or French fries or ice cream?

"It is, I believe, incorrect and unjust to put the blame on any single ingredient, any single product, any single category of food," Muhtar Kent, chief executive officer of Coca-Cola, told The Wall Street Journal in an interview published June 18. "This is an important, complicated societal issue that we all have to work together to provide a solution," he said.

Still, the trend appears to be building slowly in favor of greater government intervention, despite any uncertainty about effectiveness. The first battleground was the public schools, a 15-year fight to remove sodas and junk food from campuses and cafeterias.

The snack food and soda industries resisted every inch of the way, recounts Margo Wootan, director of nutrition at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which often challenges industry positions on health policy. "We were completely outspent and outgunned with their billions [of dollars] and donations and highly paid lobbyists versus our paltry public-health budget."

Efforts continue in many schools to improve student diet and lifestyle (see story, "Obesity in America: Schools on front lines of the fight"), but government anti-obesity efforts have also moved into other avenues, primarily soda taxes, zoning rules to restrict fast-food restaurants or to encourage healthy food options, and mandatory calorie counts on menus.

In 2007, the Los Angeles City Council instituted a two-year moratorium on new fast-food outlets in low-income South Central L.A., the first health zoning law in the US. In 2010, the town of Baldwin Park, Calif. – the reputed birthplace of the "drive-through" restaurant – put a nine-month ban on the construction of new drive-in food emporiums.

"The recent efforts by L.A. to decrease fast-food consumption in South Los Angeles through restrictive zoning suggest that this may be an increasingly popular strategy for local governments to address the rising obesity epidemic," Ms. Vestal says. "If zoning restrictions for fast-food restaurants can positively change the local food environment and decrease excess calorie consumption among residents, then there is a potential to significantly improve the community health." But she also has a cautionary note: "Fast-food consumption is not the only contributor to obesity and, thus, limiting one source of unhealthy food may not have the intended effect of reducing obesity."

As for mandatory calorie counts on menus at chain restaurants, they are required statewide in California and Vermont, as well as in five counties in New York State, New York City, Philadelphia, Montgomery County in Maryland, and King County in Washington. The menu requirement is also part of President Obama's 2010 health-care law, although the administration has not issued final rules on compliance.

"Three-dozen studies show eating out more frequently is associated with obesity, higher body fatness … and menu labeling is helping to reverse that," says Ms. Wootan, citing two recent studies:

•Consumers ordering off menus with calorie counts order meals with about 120 fewer calories than when using menus without such counts, according to a 2011 survey by market researcher NPD Group.

•Parents of children ages 3 to 6 presented with McDonald's menus with calorie labeling ordered meals for their children totaling 100 fewer calories, on average, than parents with menus without labeling, according to a 2010 survey published in the journal Pediatrics.

Some restaurant chains – Applebee's, Starbucks, Au Bon Pain, and Denny's, to name a few – voluntarily include calorie counts or have added low-cal meals to their menus.

"The whole obesity epidemic ... is explained by an extra 100 calories per person per day," Wootan says. "Seemingly small changes make a bigger difference than most people in the press and public really understand."