9/11 Memorial: At site of terror, a site of grace (video)

Loading...

| New York

This Sept. 11, 10 years after the terrorist attacks, the dedication of the 9/11 Memorial in New York will evoke many emotions: reverence for loved ones lost, gratitude for brave first responders, love of country, perhaps some uplift and peace.

In a solemn ceremony, the families of the victims – as well as Presidents Obama and George W. Bush – will look out on two massive waterfalls that pour into pools formed in the footprints of the former towers of the World Trade Center. The water disappears into dramatic black voids. All around the pools are the names of the victims, incised into bronze sheeting.

Instrumental in bringing about the memorial are three Americans who were strangers on 9/11 but ultimately became linked by the terrible events of the day.

Joe Daniels emerged from a subway station to see the North Tower of the World Trade Center ablaze. "Like everyone around me, I was transfixed looking up at the hole in the building," he says.

From his East Village bedroom window, Michael Arad could see smoke coming out of the towers. He went to the roof of his building and watched United Flight 175 swoop down the Hudson River and crash into the South Tower. "It was unbelievable, a very difficult thing to see," he recalls.

Early in the morning in San Francisco, Peter Walker was alerted to the events by his wife, who was in Indiana. Like millions of Americans, he watched as the television networks replayed the scenes. "That's probably one of the most shocking things anyone has ever seen," he remembers thinking.

This is the story of how these three men turned their initial shock into a memorial, transforming the gaping wound in the ground, a reminder of 2,977 lives lost, into a place of serenity, reflection, and grace.

Around the time of 9/11, Mr. Arad, an architect, worked for the New York City Housing Authority. As he thought back on the tragedy later that year, he pulled out his sketch pad. He drew the Hudson River, the World Financial Center, and the marina, all adjacent to the collapsed twin towers. Where the towers would be were two voids, holes in the ground.

[ Video is no longer available. ]

"I was intrigued by that idea," he says. "I ... spent a lot of time trying to understand the aesthetic, how the image could be made into reality."

He built a model and took it up on his roof, where he photographed it.

Arad ended up making an anonymous submission to the competition for memorial designs. It was one of 5,201 entries. He envisioned an urban plaza at ground level – unlike the master plan for the site, drawn up by architect Daniel Libeskind, which had the memorial 30 feet below grade.

Making it all at ground level and completely flat was essential to his plan. "It creates this unified precinct; it marks it as a space," he says.

In the middle of the plain would be the two voids, with water falling into them.

"As you walk up to the body of water, there is a moment of sad comprehension for visitors," he explains. "You understand the scale and magnitude of what happened here."

By 2003, he found out his design was one of eight finalists. But the jury choosing the design was concerned that Arad's proposal seemed austere.

That's where Mr. Walker came in. A landscape architect based in the San Francisco area, he had been involved in other memorials in the past, so he was familiar with the emotional issues, he says. When Arad called him, he agreed to work with him.

The jury of architects, public officials, and citizens deciding which design to use wanted to know if trees could be planted without losing the concept of a plain.

The idea resonated with Walker, who viewed the plain as an important "metaphor for the earth," while "trees, of course, represent life."

By January 2004, Arad and Walker's design was chosen.

The next year, Mr. Daniels, a lawyer who was working for a consulting firm, became general counsel for the nonprofit National September 11 Memorial & Museum. That organization was being formed to raise money for the memorial as well as the museum, which is scheduled to open next year.

Within 10 months, Daniels received a "battlefield" promotion to run the operation. A big part of his job was trying to come to agreement on various issues among many different constituencies – the families of the victims, commercial interests, local residents, the general public, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owned the land.

"You could literally be bogged down forever," he recalls.

In the meantime, Arad began the process of trying to implement the whole concept, which included building two waterfalls that would be the largest man-made ones ever. He wanted each waterfall to be composed of separate strands that meet halfway down.

"It is analogous to how names are commemorated on this memorial where each name has its own autonomy, its own identity, but it's also part of a much greater assembly of names," he says. "This was one of the things that defined the memorial ... the ability to acknowledge both individual loss and the collective loss."

Arad also addressed the thorny issue of how to place the names around the pools. Should they be random? Should they be alphabetical? Should the first responders have their own section?

Arad reached out to families to ask what was important to them. "How can we mark that in a memorial," he wondered, "so the placement of the names relative to every other name carried an embedded meaning and might be hidden to many people? But once it's embedded in the design, it can be teased out in many different ways – through a printed guide, an audioguide, through first-person accounts, through curated accounts."

It took two years to settle on the concept of "meaningful adjacencies," where names are placed in a way that reflects families, friends, people who commuted to work together every day, or those who went to school together many years ago. Some 1,200 requests came in from the families, and it took another year to arrange the names.

This resulted in nine groups, representing the four flights that were hijacked, the two towers, the Pentagon, the first responders, and the victims of the World Trade Center bombing in 1993. Each group contains smaller groups.

In some instances, it was necessary to place the end of one group next to another group. For example, two brothers, John and Joseph Vigiano, both died on 9/11. One was a firefighter; one was a police officer. "We knew we would have to end one group here and start another group there to allow the two names to be placed next to each other," Arad says.

While he was working on the names, Walker was trying to find the right trees for New York City. "New York is a very, very tough place for a tree to grow," he says. "The trees are not in loamy soil with perfect drainage and irrigation and all that kind of stuff, so they get stressed."

Nonetheless, the trees became an integral part of the design. Walker ended up using white oaks. He adds, "We wanted the trees to have straight trunks that go up and branch out in a vase shape so when you go down the row, they would form a kind of Gothic arch, which is referring to the arches that were at the base of the World Trade Center originally."

As Walker and Arad fine-tuned their plans, Daniels was raising money. As of mid-August, donors in all 50 states and 60 countries had contributed $406 million, enough money to open the memorial this year and the museum next year.

"This memorial, this project, is going to define part of this country forever, and people have a very natural and positive instinct to want to be part of it," says Daniels, who is trying to raise another $20 million. All total, after public funding, the project will cost $700 million.

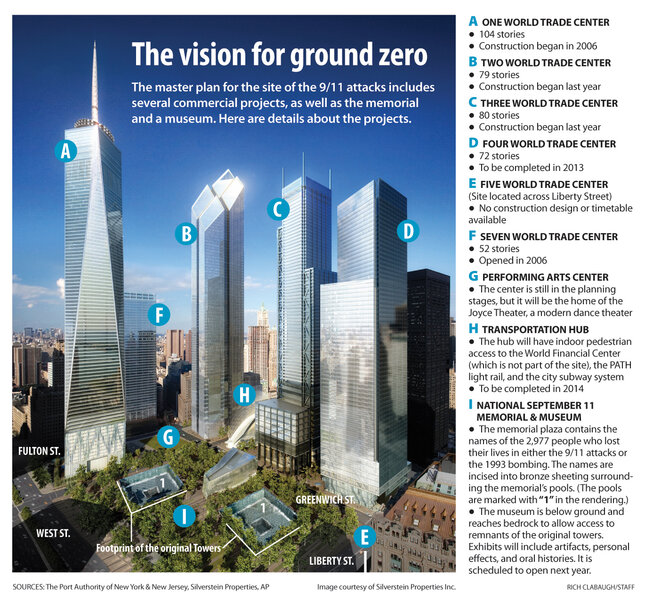

In addition to the memorial, construction has been going full-bore on several commercial projects in the area, including One World Trade Center and Four World Trade Center. As of late August, 1 WTC was 80 stories high (out of 104), and the other building was 48 stories.

Under the master plan for the site, no morning shadow from any of the buildings will fall on the memorial on this and future Sept. 11s.

Immediately after 9/11, Arad remembers walking to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. Scores of other New Yorkers, mostly strangers, came together to come to terms with the attacks. "That is to me what I remember about 9/11 – the courage and compassion and resilience that New Yorkers showed," he says.

He can envision his memorial having the same impact. "I can see someone sitting here in that once-in-a-lifetime moment and having an incredible emotional experience, and somebody sitting there eating their lunch and then going across the street to their office. Those two experiences not only can exist, but should," he says.

Daniels hopes that the memorial helps the families – that once they see the names of their loved ones and the respect accorded them, it will help bring some peace. This summer, he says, he took a woman – now raising her three sons who had lost their dad in the tragedy – to the memorial site when the waterfalls were being tested.

"Just to see her reaction to it and the sense of all the different people, all the different occupations that have been working towards memorializing her husband and her kids' father – it was a very uplifting feeling for her. And hopefully, it is representative of how family members in general take it in," says Daniels.

Walker hopes that the memorial and plaza feel like a great cathedral to visitors.

"When you think about it, when you go in it's very deliberative," he explains. "Then ... it's all about going out into the world again, and you are refreshed.... You know that life does go on."