Recovering US job market is leaving black men behind

Loading...

| Philadelphia

The jobs landscape is bleak for any unemployed American, but for black men it's virtually a desert.

For them, the Great Recession not only led to the largest increase in unemployment for any category of American worker, but it also is pinching a lot longer. About 1 in 6 black men over age 20 in the labor force is jobless – and that number has barely improved since the economic recovery officially began two years ago.

In Detroit, Las Vegas, Milwaukee, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and several other US cities, Depression-era unemployment rates above 20 percent beset the black community, estimates one economic policy group, citing government data. Moreover, the problem may get worse because city governments, which traditionally employ many African-American men, are laying off workers to cope with budget shortfalls, say experts on black employment.

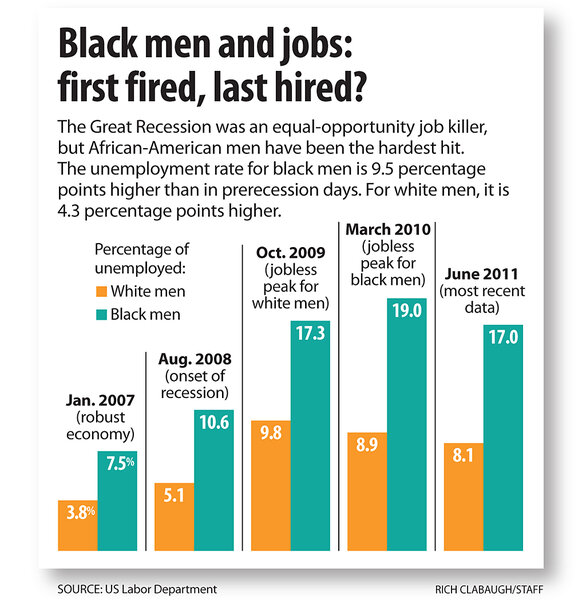

The change has been dramatic. The jobless rate, 7.5 percent in prerecession days, is now 17 percent – more than double the rate for white men. The ramifications are dramatic: a slide out of the middle class; greater dependence on public assistance; new strain on families, including the challenge of meeting mortgage or child-support payments; and more homelessness.

US Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D) of Missouri, chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, sees a long-term travesty for the whole nation if intervention is not redoubled to address the scourge of black unemployment. "The failure of this nation to address this problem will lead to another 25 years of problems in this country based on race," he says in a phone interview. "We ignore this crisis at our national peril – on the agenda are poverty, medical problems, crime, you name it."

Black men find it harder to land jobs for many reasons. Competition is fierce – in June, 4.7 unemployed job seekers for every opening – and a single blemish on a résumé can mean an employer will choose someone else. Among other hurdles for African-American men:

•A disproportionate number have criminal records. Black men are incarcerated at more than six times the rate of white men and 2.6 times the rate of Hispanic men, reports Human Rights Watch.

•Fewer have college degrees, which are a big bonus in the job market. Among men, 17.9 percent of blacks over 25 have college degrees, compared with 34.2 percent of whites, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

•Semiskilled jobs and unskilled jobs, which are often filled by those without a college education, are on the decline.

•Federal spending is likely to shrink, including funding for programs aimed at reducing black joblessness.

•Racism persists in hiring and firing despite antidiscrimination laws, studies show.

Nate Robinson of Philadelphia lost his job to the recession – and he's been struggling ever since. He was selling cars at a General Motors dealership that closed in 2009 when the auto giant entered bankruptcy and went through a restructuring.

"When I got hired, the [dealership's] manager said, 'You are going to help put GM back on the map,' " he recalls. "After they went out of business, it was kind of hard to get back into it."

While he looks for work – sometimes finding temp jobs – Mr. Robinson tries to survive on welfare. An inability to find permanent work led to personal problems and substance abuse, but for the past nine months he has been drug-free, he says.

Unemployment has pushed him out of the middle class and into poverty: The welfare checks total $102.50 every two weeks. "So I have no money in my pocket," he says. "But I'm not complaining. I know God has something out there for me."

Robinson now bemoans the fact that he never went to college.

The 'education gap'

The education gap is what stands out to John Silvia, chief economist at Wells Fargo Securities in Charlotte, N.C. It makes black men more vulnerable to job loss, he says. "We know the unemployment rate for college graduates is 4.5 percent," says Mr. Silvia. "A lot of black men do not have a college degree, and because of the changing nature of the workforce – oriented more toward education, finance, and IT [information technology] – they don't fit into the jobs that are available."

The disparity in college education between black men and other prospective hires has persisted for the past 10 years and is especially glaring in the sciences. "African-Americans are incredibly underrepresented in these fields," says Betsey Stevenson, a Labor Department economist. Only 3 percent of black men work in professional, scientific, and technical services, where job growth is occurring, according to government figures.

Math and science were never his strong suits, says Craig James of Philadelphia, who is looking for work. But he envisions himself going back to school, perhaps for computer courses, once he lands a job. He graduated from high school three years ago. The main impediment to continuing his education now is that he is a single parent of a young son.

"I know you've got to learn to use technology," says Mr. James, who was laid off last year from a job in the security industry because, he acknowledges, he "messed up" by not following all company rules and by arriving late to work. His last job was talking to students about the value of an education for the nonprofit group Mothers In Charge. The group scaled back when some of its funding from the Obama stimulus package ran out.

Now, with 3-year-old Zakia to care for, James says he has become more responsible. "My son made me stronger," says James, who lives with his parents and Zakia in North Philadelphia. He's looking for work but says he is frustrated that he has had no callbacks.

Criminal records and discrimination

By the time they were 30, 22 percent of black men born between 1965 and 1969 had been incarcerated, compared with 3 percent of white men the same age, according to one study. And surveys show that a majority of employers are reluctant to hire someone with a criminal record.

On Tuesday, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) held a commission meeting to examine whether criminal background checks were adversely affecting the job prospects of workers of color. In 1990, the EEOC concluded that “an employer may not base an employment decision on the conviction record of an applicant or employee absent business necessity.” According to the National Employment Law Project that means employers must take into account reasonable factors such as the age and seriousness of the offense in relation to the specific job at issue

On a recent morning at a career center on New York's Staten Island, Jamal Lumpkin, who left prison in September after serving 10 years for drug-related crimes, recounts his job-seeking experience. He says several interviews went well – until the employer asked about criminal background.

"When we get out, nobody wants to give us an opportunity," says Mr. Lumpkin. He has started to feel desperate, he says.

Employers' perceptions about criminality among black men may even affect job prospects for African-American men who have never done time. One study found that black men without criminal records "have as much difficulty [getting hired] as white males with a criminal record," says Algernon Austin of the Program on Race, Ethnicity and the Economy at the Economic Policy Institute, a Washington think tank. "And black males with a criminal record are worse off than black males without one."

Discrimination remains an issue, too. When a Chicago fair employment group sent out "matched pairs" – that is, white and black people with the same credentials – whites were offered jobs 16 percent more often than African-Americans were, says Christine Owens of the NELP, which advocates on behalf of the jobless.

Municipal jobs, which many African-Americans see as a haven from racial bias, are in short supply these days. There are 430,000 fewer government jobs since the recession ended in June 2009, according to the Labor Department's Ms. Stevenson.

"We have flocked to government by the throngs," says Congressman Cleaver, "because it represented opportunity and a place where you are least likely to experience racial bigotry."

What to do?

The Obama administration – which is, after all, led by an African-American man – is hardly oblivious to lingering racial bias in the workplace or soaring black male unemployment. Labor Secretary Hilda Solis, in a phone interview, says she has beefed up her department's investigative division, which deals with workplace bias and other illegal practices. "We have almost doubled and tripled investigations," says Ms. Solis, compared with 2008 levels.

She outlines some Labor Department efforts to help connect unemployed African-Americans with better jobs:

•Job Corps, an education and training program for young people. Some 78 percent of people who complete the program land a job in fewer than nine months, Solis says.

•A pilot program for military veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. It sets aside 300 slots for veterans at Job Corps centers in Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri that serve large minority populations.

•A partnership with the Department of Justice to provide job and mental-health counseling to federal and state inmates before they are released. "Once [former convicts] get hired, companies find they are some of the most loyal employees," says Solis.

•A push to give federal incentives to companies that scale back employees' hours rather than lay off workers. The administration backs such "work share" legislation, saying it preserves jobs and opens up more job opportunities, including those for black men.

In Congress, meanwhile, black lawmakers are "moderately" optimistic about a bill that would funnel US grant money to parts of the country that have seen 30 years of high poverty levels. US grantmaking agencies would target 20 percent of such funds to those areas, says Cleaver. Key Republicans with whom he has met have no objection to the legislation, he says. "There are about 80 congressional districts where there are such areas," he says.

Still, these days Congress is cutting more programs than it is adding. And it has yet to reauthorize the Workforce Investment Act, which sends money to states, cities, and counties for job training and counseling.

Frustrated by Washington's slow pace at addressing job creation, the Congressional Black Caucus plans to bring job fairs to five cities – Cleveland, Atlanta, Detroit, Miami, and Los Angeles – starting Aug. 8. It has lined up companies to attend and hopes to see 10,000 workers hired as a result. "Realizing [that the US in June] only created 18,000 new jobs, this is a pretty big number," says Cleaver.

•Patrick Wall in New York contributed to this report.