Arizona immigration law and illegal immigrants: state of extremes

Loading...

| Phoenix

Russell Pearce and Martin Escobar are divided by heritage, history, and a new law that rekindles an old fight about America's borders.

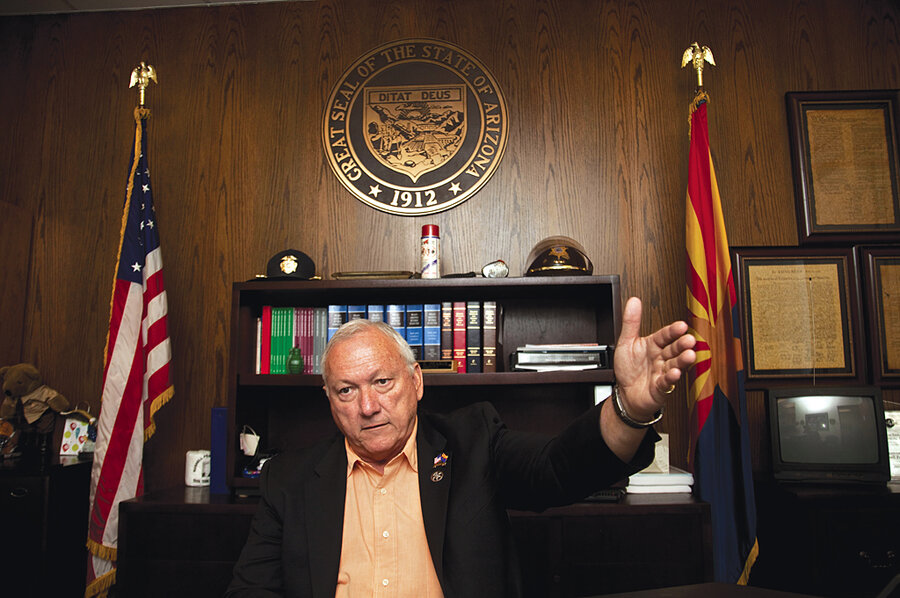

Mr. Pearce, a fifth-generation Arizonan, is the state senator who introduced the toughest illegal-immigration bill in the nation. The immigration law is so controversial that the nation is asking: What's the matter with Arizona?

" 'Illegal' is not a race," Pearce says. "It is a crime."

Mr. Escobar, born in Mexico and raised in Arizona, is a Tucson police officer who opposes the new law that gives cops broader powers to crack down on illegal immigrants. He is taking the battle to the courts.

"When I saw the law and I read it, I actually never imagined it would get signed," he says. "I saw it as a personal attack on the Hispanic community."

Senate Bill 1070, which takes effect in July, is a historical marker in this ever-changing, ever-growing state of extremes.

You don't like the bill? A lot of Arizonans don't care. Polls show widespread support for it.

The state where lawmen Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday mowed down outlaws at the O.K. Corral now brings its modern brand of western justice to illegal immigration: attrition through enforcement.

After any lawful stop, police can "determine the immigration status" of those they suspect of being in the country illegally.

Proponents say enough is enough, and it's time to crack down on illegal immigration after years of inaction by the federal government. Opponents say the new law will lead to racial profiling.

Depending on your point of view, Arizona's new law is a national model or a national disgrace. And the measure has embroiled many municipalities and organizations in debate over economic boycotts of Arizona.

"You can't break into my country, just like you can't break into my home," Pearce says.

But, says Escobar, "the level of hate and demonizing that is now attributed to the undocumented is unprecedented."

The conflict over immigration has caused people here to take a second look at their home.

What exactly does Arizona stand for, beyond the ever-present sun, golf, and the Grand Canyon?

"Arizona is a land of possibilities," says Marshall Vest, an economist with the Eller College of Management at the University of Arizona in Tucson. "It's a place where a man can take his family in hopes of making a better life. That has been true all the way back to the 1800s."

• • •

Arizona is home to right-wing republicans, New Age gurus, and vast native American reservations. It is where housing boomed through the 1990s and went bust in the first decade of the 21st century.

It is young – half a million of the state's residents are under the age of 5. And it is old – "active retirement" was born here during the 1960s when Del Webb's Sun City rose in the desert with homes, pools, and golf courses that became magnets for seniors.

"I meet all kinds of people: People born before statehood and those who moved here just six months ago," says Marshall Trimble, Arizona's state historian. "I find a common thread for everyone is the beauty of the place and cultural diversity, which I know goes against the national stereotype of us.

"The land is more diverse than any place in the nation," he says of the richly forested north and searing deserts of the south. "And the state has that Old West attitude of independence and self-reliance."

Arizona's stubborn independence from the rest of the country was infamous during the decade it resisted recognition of Martin Luther King Day as a holiday before finally accepting it in 1993. Arizona is also the only mainland state that does not use daylight saving time, preserving early golf tee times and earlier darkness for drive-in theaters, among other reasons. And its reputation for law and order includes the peculiar (a sheriff who made prisoners wear pink underwear) and the serious (violent spillover from Mexico's drug and human smuggling that has caused the state to be dubbed the nation's kidnapping capital).

US Sens. Barry Goldwater and Mo Udall defined old Arizona, practical men on opposite political sides who sought to get things done for the good of the state. Sandra Day O'Connor, another Arizonan, brought similar skills of compromise to the US Supreme Court.

"Unfortunately, I'll probably get myself in a sling for saying this: I think right-wing Republicans have taken charge, and I'm sad to see that," Mr. Trimble says. "I was a Barry Goldwater Republican."

Characters dominate the state's history, Trimble says, people like William Owen "Bucky" O'Neill, a gambler, lawman, newspaperman, and politician who rode with Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders and was killed in Cuba; and Nellie Cashman, an Irish immigrant who landed in Tombstone.

"Most people think the women who came west to work in towns like Tombstone were prostitutes and madams," Trimble says. "Nellie Cashman was an entrepreneur. She opened up a boardinghouse and made a fortune."

• • •

People still come to Arizona to make their fortunes and feed their families. Some 700,000 people moved to Arizona from other states between 2000 and 2008. And more Mexican migrants coming into the United States without documents are apprehended here than in any other state.

Buried in the debate on immigration is a profound demographic change in a state of some 6.5 million people: About 30 percent of the population is Hispanic.

The swift growth of the state's Hispanic population has created a "cultural generation gap," writes William H. Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

In Arizona, the population of those 65 and over is 83 percent white; the population of those 18 and under is only 43 percent white. That gap – 40 percent – is the highest among the states.

"Is Arizona out of touch with the rest of America?" asks Mr. Frey. "Or, is it the precursor of things to come elsewhere?"

Around 400,000 undocumented residents are believed to be living in Arizona. They're people like Alejandra Valenzuela, a straight-A student at Carl Hayden High School in Phoenix.

Ms. Valenzuela spoke recently at a protest led by New York civil rights leader the Rev. Al Sharpton. She stood at the pulpit of Pilgrim Rest Baptist Church, speaking to a packed congregation that included Hispanics, African-Americans, and whites, politicians, labor organizers, and religious leaders. She told her story of traveling with her mother to the US from Mexico after her father died 10 years ago. It took several years to learn English, but she was fluent by fifth grade.

"I didn't know I was undocumented until I got to high school," she said. Later, in the audience signing a letter calling on President Obama to stop the Arizona bill from taking effect, she reflected on her dreams, which aren't much different from those of other Arizonans: "All I can do is to continue my education. I love this country. I have a lot of hope."

• • •

But just whose Arizona is this, anyway? Pearce, the state senator, was born poor, his father an alcoholic, his mother a bank teller. John Wayne was his hero.

"I liked the good guy," says Pearce, sitting in his Senate office, dressed in cowboy boots, jeans, a belt buckle the size of a fist, peach-colored shirt, and blue blazer.

He became a lawman, just like "The Duke" of movie westerns. He served in the Maricopa County Sheriff's Department for 23 years, rising to chief deputy. On the job, he was shot by gang members in the chest, and lost a chunk of a finger.

Elected to the state house of representatives in 2000, Pearce quickly earned a reputation as a staunch foe of illegal immigration, proposing two hard-line enforcement bills that failed. This time he found success, the bill matching the mood of the public and fellow Republicans, including Gov. Jan Brewer, who signed it.

"The majority of Americans love what we're doing," he says. "They know it's the right thing to do."

Escobar, the patrol officer from Tucson, is on the other side of the issue. Born in Mexico, he came to Arizona when he was 5. His father was a carpenter; his mother was a hotel maid and worked in a dry cleaning business and a tortilla factory.

As a kid, Escobar dreamed of being a veterinarian, fireman, or police officer. Law enforcement won out. He isn't a cop 24/7, though. He runs a martial arts academy specializing in jujitsu.

"I have emotions, I'm compassionate," he says of his role as a cop, a husband, and a father. "That is the part some people don't get."

He says the new law puts him in a tough spot: "How can you tell who is here legally and who is here illegally just by looking at them?"

Escobar fears that illegal immigrants who are victims of crimes, including spousal abuse, may be too afraid to come forward to police. "The trust will go away."

That theme – a loss of trust – is echoed by another police officer who has also challenged the bill. David Salgado, a patrolman with the Phoenix Police Department, says the new law will drive a wedge between undocumented residents and the police.

Recently, Mr. Salgado says he parked his squad car by a youth center in a Hispanic neighborhood to do paperwork. "Cars passed by, and people wouldn't even make eye contact," he says. "Usually people will wave or make eye contact. This crisis has already started. The trust with the Hispanic community went down the drain because of this bill."

Emotions are running high in the concrete geometry of the cities. And those emotions are matched at the parched, wide-open spaces along the border.

The San Bernardino Valley is a place of raw beauty and hard living, tucked into the state's southeastern corner, in Cochise County, across the border from Mexico. It's where old Arizona grew on the back of the three C's – cattle, cotton, and copper.

"We can take the heat; a lot of tough, long days, but that's part of living," says Wendy Glenn, a rancher whose calloused hands and tanned face are emblems of a lifetime tending the land. "It's a way of life. Open country, working with animals."

She and her husband, Warner Glenn, a third-generation rancher, run the Malpai Ranch. Most times, it's peaceful around here, a place where cattle outnumber residents and where the rustling of the wind cuts through the loneliness. In the last decade, though, Ms. Glenn says thousands of illegal immigrants have cut across their land. A woman once gave birth in the Glenns' pasture. Others have stopped by the front door for food and water.

On March 27, violence cut through the valley. Glenn's neighbor, a well-respected rancher named Robert Krentz, was gunned down. No suspects have been arrested. Other ranchers believe the murder was committed by an illegal immigrant who fled to Mexico.

The last time Glenn heard from her neighbor was the morning of his death, his voice echoing from a VHF radio used by several families in the valley: "I heard him at 10 a.m. He said there was an illegal out here and to call the border patrol."

When Mr. Krentz didn't return home, the valley families knew there was trouble. Before midnight, his body was located. Trackers, including Glenn's husband and daughter, say they followed the suspect's trail to the border.

Glenn tears up as she says, "He will be sorely missed, a really good guy, intense and a hard worker. What a terrible thing."

Don Kimble, another rancher, misses his friend so much: "I thought my dad was the easiest-going, most common-sense type man in the valley. But that was Rob. There wasn't a nicer guy."

Mr. Kimble and Krentz went to school together at a one-room schoolhouse. Later they served together on the school board.

Kimble is a third-generation rancher whose face is as weathered as the land. There is dirt beneath his fingernails. A band of sweat stains his cowboy hat.

"There's nothing better than a good horse or a good day," he says.

He has no quarrel with illegal immigrants who head north for jobs. But he is angry with the "coyotes" who lead people across the border. He blames them for cutting water lines and damaging fences. And he blames them for the drug trade.

"I've run into an Uzi," he says. "I've run into an AR-15. And I've run into an AK-47. I carry a .38 pistol in my pocket for rattlesnakes. My .38 pistol would be nothing against an AR-15."

He says it was time for a new law. The federal government wouldn't deal with the immigration issue, so the state stepped in. "The government has to protect its citizens. We're just as important as the people in Tucson. There may not be as many of us but we're important. They have to seal the border."

Related stories:

Arizona's new immigration law makes sense

After Arizona, why are 10 states considering immigration bills?