Catholics face moral crisis between healthcare reform and abortion

Loading...

The healthcare reform debate could soon bring many Roman Catholics to a wrenching moral dilemma: Should they support a bill that expands healthcare to the poor, even if it involves so many uncertainties surrounding access to abortion?

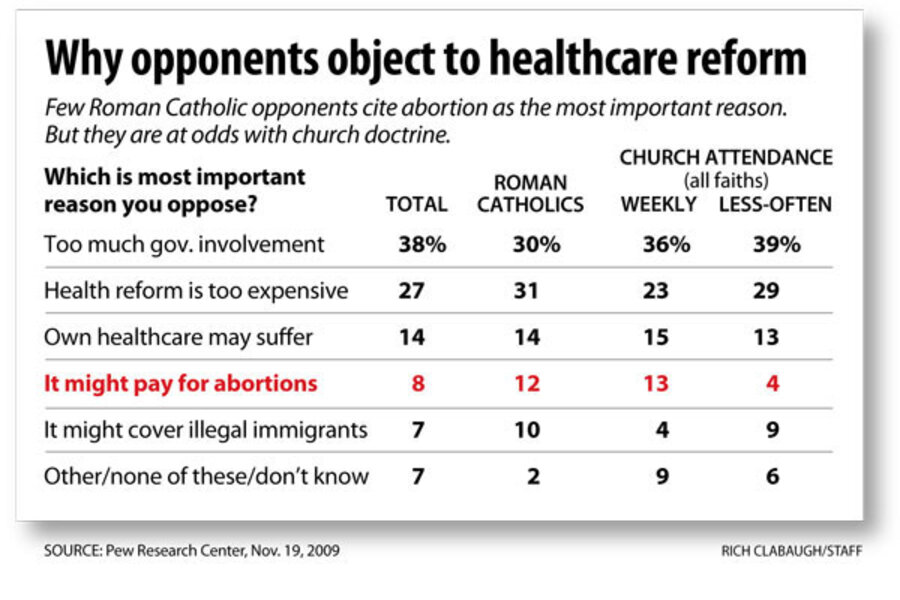

For months, bishops have made their guidance plain: If the final bill weakens a ban on public funding for abortion, then Catholics should oppose it. But they are finding many of their antiabortion adherents willing to embrace what they see as a greater good – improving access to healthcare – even if it undercuts the church’s stand against abortion.

For Chris Korzen, executive director of Catholics United, a 50,000-member lay movement that pushes for public policy to reflect Catholic social teachings, Catholics must have open minds: “The wrong thing would be for anyone to be so firmly entrenched in their positions on federal funding of abortion that they’re not willing to come to the table and talk about a compromise.”

Healthcare reform is a historic opportunity, adds Victoria Kovari, interim president of Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good, a 45,000-member advocacy group informed by Catholic social teachings.

“We share all the bishops’ concerns,” she says. “The difference is [our] feeling that we would be morally remiss if we walked away from all of healthcare [reform]. We have to take seriously our call to be about what’s good for the whole human family.”

Strong support of healthcare reform

During the past decade, Catholics have overwhelmingly supported a government guarantee of healthcare access for all citizens – regardless of cost. More than 70 percent of US Catholics supported such a guarantee in 2002 and again in 2006, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) at Georgetown University in Washington.

Catholic opinions on abortion rights have been more evenly divided. But opposition to abortion rights has been growing, and certain types of Catholics – such as minorities who struggle to pay for medical services – are likely to be especially conflicted about the tension between healthcare and abortion, says John Green, a political scientist at the University of Akron in Ohio who studies religious dynamics in politics.

The issue is contentious in congressional debates, too. The question is not whether tax dollars ought to directly fund abortion; most lawmakers and President Obama agree they should not. Rather, the question is how to limit public money for insurers who cover abortions while still guaranteeing access to the procedure.

When the House passed its version of a healthcare reform bill in November, it included an amendment that explicitly bans federal funding of abortions through the new insurance exchanges created by the law. The Senate has also struggled with the abortion issue in its version of the bill, currently under debate. A similar amendment to restrict abortion funding has been proposed, but is not expected to be a part of the Senate’s final version of the bill.

According to Catholic social teachings, both access to healthcare and the right to life are basic human rights. The church requires Catholics to oppose abortion. But it also compels them to search their consciences for how best to advance the common good – without cooperating with evil – in societies where abortion is legal. In practice, that means grappling with shades of gray, says Thomas Massaro, a professor of moral theology at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry.

“It’s a very difficult struggle,” he says. “There’s no formula ... for a legislator to vote up or down based on a simple, cookie-cutter determination.”

Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D) of Rhode Island made news last month when he upbraided his bishop for counseling him not to take communion, because Mr. Kennedy has consistently voted for abortion rights. Kennedy also criticized bishops for threatening to oppose the bill over abortion.

The moral battle lines

But Catholic bishops say it’s paramount to give no ground on one principle: No one should be compelled to help pay for anyone else’s abortion. “There’s leeway in terms of supporting legislation that does good things, but not as much good as we hoped,” says Richard Doerflinger of the Secretariat of Pro-Life Activities at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. “There isn’t any leeway on changing the law to promote direct killing more widely” through abortion.

Other antiabortion Catholics, however, note that governments are not individuals. Everyone is apt to have moral qualms about something in a trillion-dollar budget, Mr. Massaro says, but that doesn’t make taxpayers as morally culpable as, say, individuals who have abortions.

Moreover, the federal government already supports abortions in some ways. Women are permitted to deduct the cost of an abortion on their tax returns as a healthcare expense, says Mr. Korzen.

As Catholics debate the issue, pragmatic concerns compete with philosophical ones. Korzen suggests that healthcare reform could actually cut the number of abortions. If more women had health insurance, he explains, then bringing pregnancies to term would be more affordable and therefore more common.

But defenders of the church’s position don’t buy that argument. The church doesn’t take moral positions on utilitarian grounds. The church urges people to shun evil – even if a measure of good could come from an evil act.

“There are moral absolutes that we can’t get beyond,” Mr. Doerflinger says.