Republicans' anti-Trump 'corrupt bargain' takes America back to 1824

Loading...

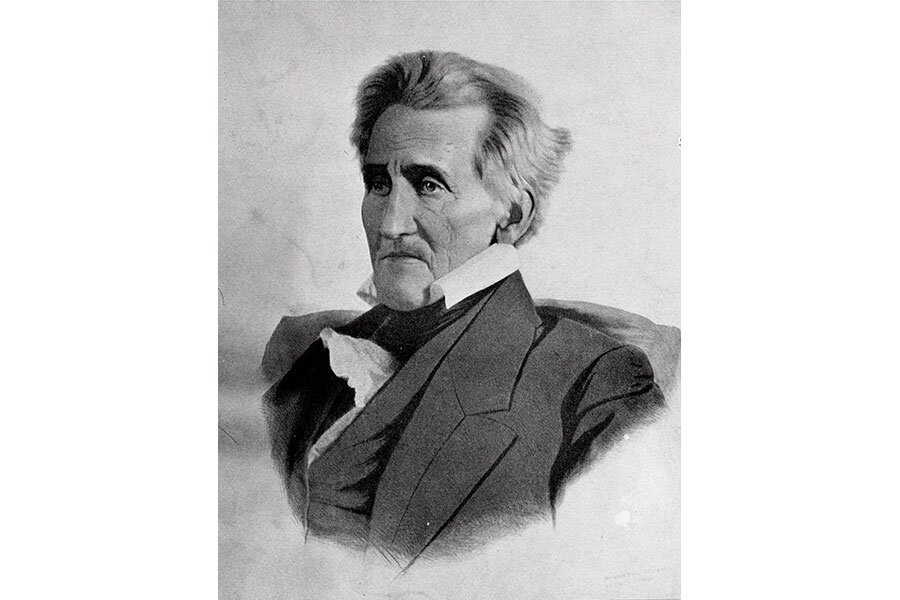

“Corrupt bargain”: Originally used to describe the events that handed John Quincy Adams the presidency over Andrew Jackson in 1824, it has come to connote any controversial deal-making among politicians.

The surprise announcement that Republicans Ted Cruz and John Kasich would join forces to try to deny the GOP nomination to Donald Trump revived the phrase. Senator Cruz and Governor Kasich said they would divide their focus on three upcoming primary states, with the Texas senator concentrating on Indiana and the Ohio governor going after Oregon and New Mexico. (Mr. Trump’s response featured his favorite adjective: “sad.”)

“Way back in February, I urged non-Trump Republicans to collude to defeat Donald Trump,” wrote Matt Lewis of The Daily Caller. “They didn’t … Until last night, when word spread that Ted Cruz and John Kasich had finally reached a corrupt bargain, there seemed to be no appetite for doing the obvious.”

Even before that development, though, some pundits had been speculatively dropping the phrase in anticipation of a contested convention:

- In The National Interest, Robert Merry wondered last week, “Will Ted Cruz Pull Off an Old-School ‘Corrupt Bargain’?’’

- The Morning Consult’s Reid Wilson noted Trump’s unhappiness with the nominating process in a March story headlined, “Trump Echoes 1824’s ‘Corrupt Bargain.’’’

- In February, Rich Lowry of National Review also invoked 1824 as a possible precedent to chaos in Cleveland if Trump leads in delegates at the convention, but is denied the nomination.

In that infamous election nearly two centuries ago, Jackson and Adams were both on the ballot for the White House, along with House Speaker Henry Clay and Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford. Because none of them won a majority of the electoral vote, the House of Representatives was charged with determining the outcome (a storyline also now playing out, in far funnier fashion, on HBO’s comedy “Veep”). In a surprise move, Adams was elected over Jackson, then made Clay his secretary of State. The events led Jackson’s supporters to denounce the outcome as a “corrupt bargain” and paved the way for Jackson’s victory four years later.

The term surfaced again in 1876, which featured an even wackier election in which Democrat Samuel Tilden was expected to beat Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. But three states – Louisiana, South Carolina and Florida – botched their voting results, leading Congress to set up a 15-member investigating committee. After being deadlocked, it hatched a plot: Southern Democrats would back Hayes if he agreed to withdraw troops from the South, ending Reconstruction. Because of the so-called “Compromise of 1877,” Hayes subsequently became known as “His Fraudulency” and “Rutherfraud B. Hayes.”

And cries of “corrupt bargain” came up in 1974 after GOP President Gerald R. Ford pardoned his predecessor, Richard Nixon, saying it was in the country’s best interests. Critics charged that the pardon came in exchange for Nixon’s resignation in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

More recently, the phrase was used in 2014, when Democrat Chad Taylor abruptly ended his challenge to Kansas Republican Sen. Pat Roberts (R) without an explanation. And when Democrats sought to use a parliamentary maneuver in 2010 to get President Obama’s health-care legislation past a wall of united GOP opposition, Republicans also invoked the term.

Chuck McCutcheon writes his “Speaking Politics” blog exclusively for Politics Voices.

Interested in decoding what candidates are saying? Chuck McCutcheon and David Mark’s latest book, “Doubletalk: The Language, Code, and Jargon of a Presidential Election,” is now out.