Bush on Bush, and the best presidential memoir never written

Loading...

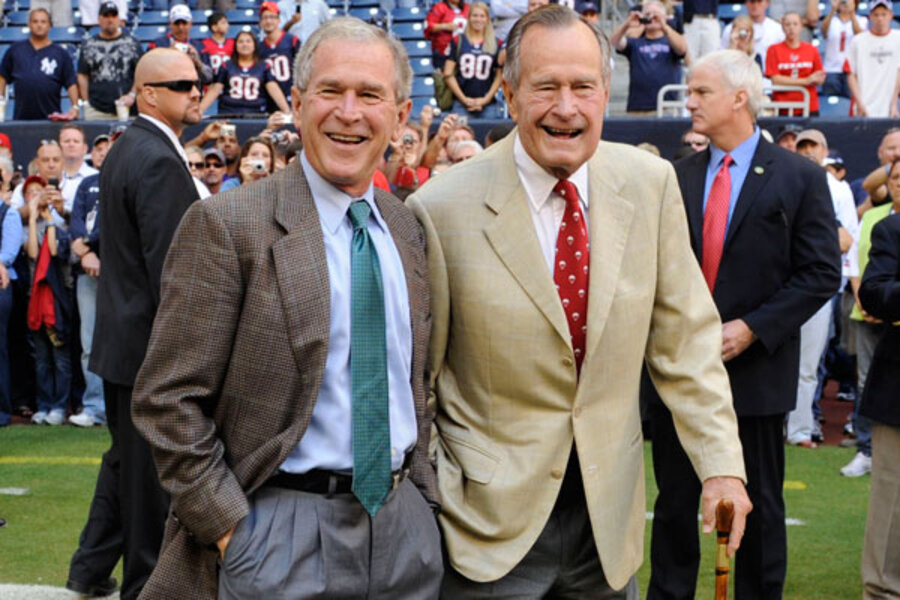

The news that George W. Bush has written a book about his 90-year old father, former president George. H. W. Bush, set off the usual partisan-based reaction among some in the punditocracy. But I, for one, look forward to reading it, not least because one could argue – as I did here – that the elder Bush is the best president never to win reelection. Moreover, it will be interesting to see whether Bush 43 addresses some of the policy differences between them, most notably how each approached the problem of removing Saddam Hussein from office.

It is worth noting that both Bushes wrote memoirs. The elder’s, co-written with his national security adviser Brent Scowcroft is, as one might expect from the title, "A World Transformed," focused on the major foreign policy decisions of his administration. The excerpts from Bush’s diary included in the memoir provide a wonderful contemporaneous view of his thoughts as he confronted a series of significant foreign policy crises, including the end of the cold war and Mr. Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Bush’s ability to put together both an international coalition to oppose Hussein as well as persuading a much divided Congress to authorize military action remains one of the great leadership feats in presidential annals. The memoir is a great reminder that history is lived by the participants looking forward under conditions of great uncertainty, but it is judged by us with the benefit of hindsight.

The son’s memoirs, "Decision Points," in contrast, looks at a series of critical decisions, both domestic and in foreign policy, that helped define his presidency. What struck me about 43’s memoir is how candid he is about the mistakes he made, including the slow response to hurricane Katrina and the decision to pursue Social Security reform ahead of immigration. Interestingly, Bush begins his memoirs by describing his decision to quit drinking – an interesting choice considering the magnitude of the other key events that he addresses later in the book. (The other important fact I learned is that 43 inherited his habit of bestowing nicknames on people from his father who most notably labeled his wife “the silver fox.”)

Hearing about George W. Bush’s latest writing venture got me thinking about the best presidential memoirs I’ve read. In my view one of the most underrated is Calvin Coolidge’s "The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge," written in sparing yet often quite evocative prose. Here is Coolidge’s description of his reaction to the death of his son, who died of blood poisoning while Coolidge was in the White House. “When he went, the power and the glory of the Presidency went with him. The ways of Providence are often beyond our understanding. It seemed to me that the world had need of the work that it was probable he could do. I do not know why such a price was exacted for occupying the White House.”

Among the more recent presidents, Reagan’s "An American Life" exudes a sunny optimism that is especially poignant given his subsequent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. Although he manages to faithfully address the major events of his life, including his presidency, his account never really penetrates deeply enough to help readers understand the inner Reagan nor the degree to which he was fully in charge of his presidency. Clinton’s "My Life," at nearly 1,000 pages, is far too long and self-indulgent, as befitting a man of such enormous appetites, and can only be read in small doses. Richard Nixon spent much of his post-presidential years writing a series of books designed, in part, to rehabilitate his public image. In this vein, his memoirs, "RN The Memoirs of Richard Nixon," are good at bringing us inside his thought process during the Watergate scandal, but he never seems willing to fully address his culpability nor the enormity of the scandal. The book begins, however, with one of the best lines to open any presidential memoir: “I was born in a house my father built.”

For me, however, the best presidential memoir is Ulysses Simpson Grant’s "Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant" which, unfortunately, does not cover his years as president. Written as he was dying of throat cancer, his account of his life up to the presidency reads much as he conducted his military command: meticulous, plain-spoken, brutally honest, and uncompromising in its opinions. I will never forget Grant’s description of his approach to battle during his first regimental command: “As we approached the brow of the hill from which it was expected we would see Harris’ camp [Harris was commanding the enemy forces] and possibly find his men ready formed to meet us, my heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.” It seems to me that this passage captures what drives most soldiers to fight rather than to run from combat – a lack of moral courage. As it turns out, Grant arrives at the expected battlefield only to find that Harris has pulled back his troops. Grant writes: “I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.” From that point on, Grant says, he “never experienced trepidation upon confronting the enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety.”

The best presidential memoirs, it seems to me, accomplish two objectives. First, they recreate as faithfully as possible the critical events of the president’s time in office as he saw them as they were occurring. What was his explanation for the course of events? What options or responses did he consider? We want to see events from his vantage point in real time, rather than have him rationalize decisions after the fact. But a good memoir should also reveal something about the essence of the president as a person – those experiences and beliefs that provide insight regarding how and why he responded to the pressures of occupying the presidential office. In this regard, how presidents choose to tell their life story, including the events they decide are important for readers to understand, are often quite revealing. The best memoirs don’t defend a president or his presidency – they help us understand both.

Matthew Dickinson publishes his Presidential Power blog at http://sites.middlebury.edu/presidentialpower/.