Does Obama face a 'competence' problem?

Loading...

“[T]he world is a mess.” So declared former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright last Sunday while appearing on Bob Schieffer’s "Face the Nation." But, if the latest round of punditry is to be believed, so is President’s Obama’s foreign policy. The Washington Post’s David Ignatius issued a blistering critique Tuesday regarding Secretary of State’s John Kerry’s efforts to broker a truce in Gaza. By targeting Mr. Kerry, of course, Mr. Ignatius’ critique will inevitably be viewed as implicitly indicting the president, who is Kerry’s boss. Ignatius’s critique comes two days after his colleague Fred Hiatt’s own attack on Mr. Obama’s policy of “disengagement.” And finally, The Washington Post’s Chris Cillizza, citing recent survey data, argued in his column Monday that Obama faces a significant “competence” problem that threatens both his ability to accomplish much during his second term and, not incidentally, “make things very tough for his party in this fall’s midterm election.”

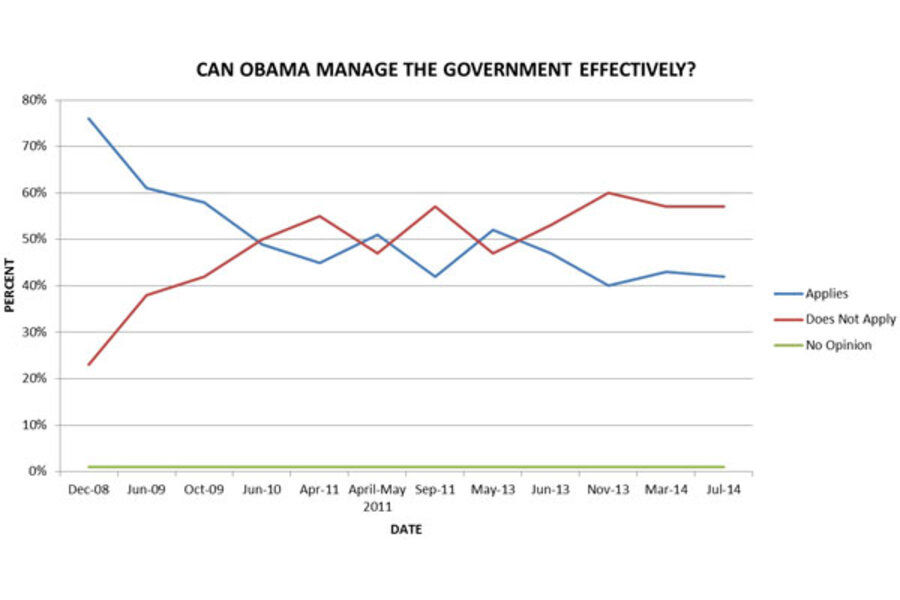

I noted in Monday’s post that much of the criticism regarding Obama’s foreign policy fails to recognize the nearly insoluble nature of many of world problems (the recurring Israeli-Palestine clash only dates back at least to 1948, after all) and overstates Obama’s – indeed, any president’s – effective influence on events in general. Today I want to develop that point by focusing on Mr. Cillizza’s latest critique of the president’s managerial abilities, which he appears to blame in part for Obama’s foreign policy failings. As evidence of Obama’s managerial incompetence, Cillizza cites a recent CNN poll in which only 42 percent of respondents believe the phrase “can manage the government effectively” applies to Obama, while fully 57 percent believes it doesn’t apply to him. To Cillizza, this is clear proof that Obama “is faltering badly on the competence question.”

What should we make of Cillizza’s argument? To start, it’s worth noting that, as Cillizza acknowledges, the latest survey result isn’t much different from the responses in previous CNN surveys asking this same question. Indeed, back in September, 2011 – before Obama won reelection – the same percentage of respondents – 42 percent – came to the same conclusion regarding Obama’s lack of managerial effectiveness. Last November only 40 percent of those surveyed said the “manage government effectively” moniker applied to Obama. In fact, as the graph put together by Day Robins (see above) and charting responses to the CNN managerial competence question dating back to 2008 indicates, views regarding Obama’s managerial capabilities seem to have stabilized: If the President has a significant competence issue, then, it is a longstanding concern that predates his reelection, and it is not nearly as certain as Cillizza seems to believe that it will have serious political implications this fall. It certainly did not prevent his reelection in 2012.

More importantly, however, it is not immediately clear what drives survey respondents’ answers to this question. What does it mean to be an effective manager? Cillizza himself seems fuzzy on this point – he attributes the low support for Obama’s managerial qualities to “[a] series of events – from the VA scandal to the ongoing border crisis to the situation in Ukraine to the NSA spying program – [that] have badly undermined the idea that Obama can effectively manage the government…” But it seems to me that some of these issues, such as the border crisis or the situation in Ukraine, aren’t viewed by most people through a narrow managerial lens, if that means evaluating whether the president is an effective administrator of policies in these issue areas. I suspect instead that when it comes to the Ukraine conflict or immigration, people are criticizing Obama’s policies, or at least the perceived impact of these policies on outcomes, more than his managerial skills. Similarly, critics of the NSA spying program aren’t attacking how it was managed so much as who it targeted and on what basis.

But even in areas, such as the VA scandal, where outcomes do seem linked to poor management, the survey evidence indicates that most people do not blame the president. Thus, a NBC/Wall St. Journal survey from last June showed that 61 percent of respondents believed that the VA problems were due to a “longstanding government bureaucracy” while only 14 percent attributed the scandal to “poor management by the Obama administration.”

But there is a more fundamental problem with Cillizza’s focus on Obama’s managerial competence. It feeds the inaccurate belief that the president is the nation’s CEO who has primary responsibility for managing the executive branch bureaucracy. This frequently voiced belief, however, flies in the face of both the Constitution and empirical evidence. In fact, the Framers allocated the primary levers of managerial control – particularly the ability to create, define a mission and pay for a government bureaucracy – to Congress, not the president. The managerial powers the president does possess, such as the ability to appoint senior officials to head the bureaucracy, is usually shared with the Senate. In some cases presidents can “manage” unilaterally, as when firing officials, although the cost of doing so is often politically prohibitive. But, as Obama discovered when debating options regarding a potential surge of military forces in Afghanistan, even a president’s “commander-in-chief”-related managerial powers are more limited than is commonly recognized. Journalists, in their reporting, often exhibit a blind spot to this constitutionally-mandated sharing of managerial powers, as Richard Neustadt noted more than half a century ago in his classic study of presidential power: “Even Washington reporters … are not immune to the illusion that administrative agencies comprise a single structure, the ‘executive branch’ where presidential word is law, or ought to be.” In fact, as the news that Congress is taking the initial steps to fix the Veterans Administration reminds us, when bureaucracies fail, we usually ought first to start with Congress rather than the president when seeking solutions.

My point here is not to absolve Obama of all blame for the “messy” state of American foreign policy. It is instead to suggest that the problems are probably not caused by his managerial incompetence so much as a poor choice of policy options and a limited capacity, rooted in weak formal powers, to implement those options. Nor do I mean to imply that a president’s managerial skills (or lack thereof) don’t matter. They do – but their biggest impact centers on how presidents choose to utilize their immediate advisers, a topic about which I’ve written extensively, and which I will try to address in another blog post. In the meantime, however, I see little evidence that Obama’s alleged lack of managerial competence is the cause of his foreign policy problems or that it will be a drag on the Democratic ticket come November.

Matthew Dickinson publishes his Presidential Power blog at http://sites.middlebury.edu/presidentialpower/.