Why GOP might be misjudging 'stolen' delegate uproar

Loading...

| Washington

Millions of pixels have been spilled analyzing the effect on the Republican Party if Donald Trump wins its presidential nomination. He’s the weakest front-runner ever! Hillary Clinton will crush him! (Or not.) The GOP might even lose the House!

There’s been less attention paid to the flip side question: What will happen to the Republican Party as an institution if Donald Trump is denied a prize he believes is rightfully his?

Open intraparty warfare, that’s what. To paraphrase "Ghostbusters": Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies, rivers and seas boiling, earthquakes, volcanoes, mass hysteria.

Well, it might not be that bad. But it would not be nothing. In any case that’s our reaction to the Drudge Report’s continuing campaign against Ted Cruz.

The Drudge Report aggregation website remains a powerful force of modern media. Its links can flood a story with hundreds of thousands of readers. Any political candidate, but particularly a Republican one, ignores or insults it at his or her peril. It’s like Rush Limbaugh in that sense, or Fox News.

And as The Washington Post’s Daily 202 tipsheet notes Tuesday, the Drudge Report has “aggressively” portrayed Donald Trump’s loss of delegates to Ted Cruz at last Saturday’s GOP convention in Colorado as a “corrupt power grab.”

On Tuesday morning, the site linked to no less than nine stories about the subject with anti-Cruz headlines. The words “rigged” and “disenfranchised” are among those used.

Analytics analysis shows that the Drudge attacks are breaking through on social media in a significant way, according to the Post. The charges are clearly bugging Cruz – he said in a radio interview yesterday that Drudge has become “the attack site for the Trump campaign.”

“This kind of squabbling will only get louder as the delegate wrestling and wrangling intensifies,” writes the Post’s James Hohmann.

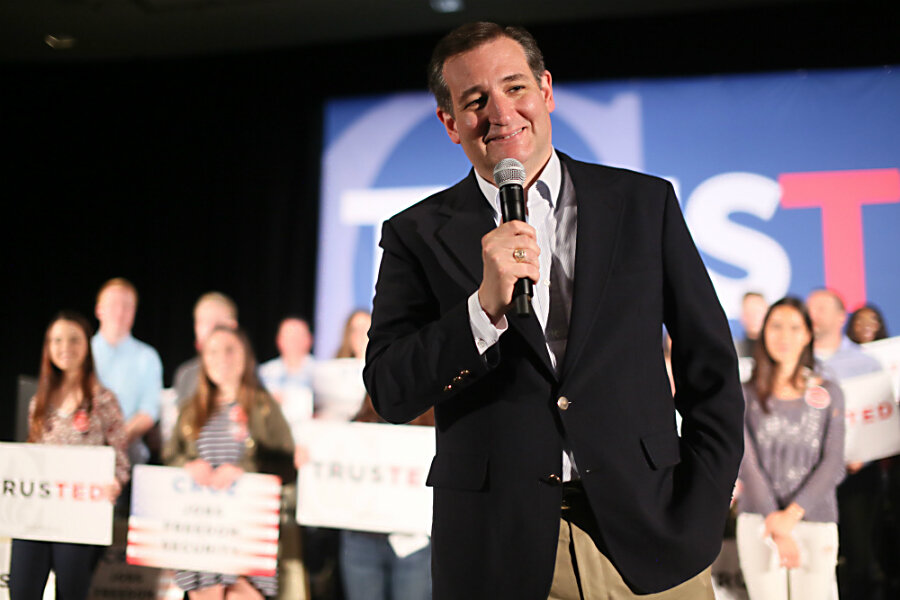

The Cruz forces, in conjunction with the wider #NeverTrump movement, seem determined to outmaneuver The Donald either prior to or at the Cleveland Republican National Convention.

If Trump arrives in Cleveland with the 1,237 delegates needed for a majority in his control, he’ll get the nomination. If he doesn’t, he is widely seen as likely to fail, as the Monitor’s Linda Feldmann wrote yesterday.

After a ballot or two, the delegates will be unbound, according to the rules, and will race to vote for whomever they actually support – probably Ted Cruz. If that happens, it means the person that finished first in the GOP popular vote, first in number of states won, and first in delegate support entering the convention, will lose. The person who was second in all those things will win.

(Yes, there’s the whole deadlocked convention scenario, where they turn to Jim Webb or a random member of the Ohio delegation as an alternative. That’s possible, but much less likely to happen.)

We think the Cruz/#NeverTrump crowd is a bit too sanguine about the possible reaction to such maneuvering from Trump supporters. Trump’s got the backing of 35 to 40 percent of primary voters, after all. Many are committed. The core is lower-income, less-educated whites. The word “stolen” is going to resonate with them.

Is the party going to just write off this demographic, or assume it will go along with whomever they choose? The operating principle among the anti-Trumps on this question seems to be sticking fingers in their ears and humming.

Trump opponents are fond of saying the rules are the rules. They aren’t cheating. They’re taking advantage of existing guidelines. Delegates pick the nominee, not voters. That’s the way it’s been for hundreds of years.

This is true, as we’ve noted ourselves. But upon reflection, we think the relevance of how Abraham Lincoln supplanted the favorite at the 1860 Republican Convention is declining.

Conventions used to pick nominees. But there’s a reason there’s been hardly any convention drama since the modern nomination process began to take shape in the post-Watergate era. Almost every move has been a step towards greater transparency and democracy. The expansion of the primary system was meant to widen support, and thus party unity, for nominees. (As recently as 1968, Hubert Humphrey won a nomination without even entering any primaries.) Caucuses are a halfway-step toward the same thing.

Today’s system is a hybrid of the old party boss approach and a pure primary-based contest. But popular voting is the foundation. It’s almost certain that Trump will enter the convention having won many more actual votes than anybody. That’s going to be very tough to ignore.

This dispute could turn into an internal Republican version of Bush v. Gore, the ending to the 2000 presidential race that roiled the nation, writes conservative columnist Byron York in the Washington Examiner.

That standoff ended with the popular vote loser in the White House and bruised feelings all around. It might have diminished American confidence in its own electoral system.

Democrats unhappily accepted the 2000 result which denied the popular vote winner the White House because at least that aspect of the controversy followed a process outlined in the Constitution, according to York. That wouldn’t be the case in a 2016 nomination battle. Rules written and amended by party activists just prior to the Cleveland convention might play an important role.

“If those rules can be reasonably viewed as unfair, they won’t command the fundamental respect and consensus of a constitutional provision. And the resulting nominee won’t command that respect, either,” he writes.