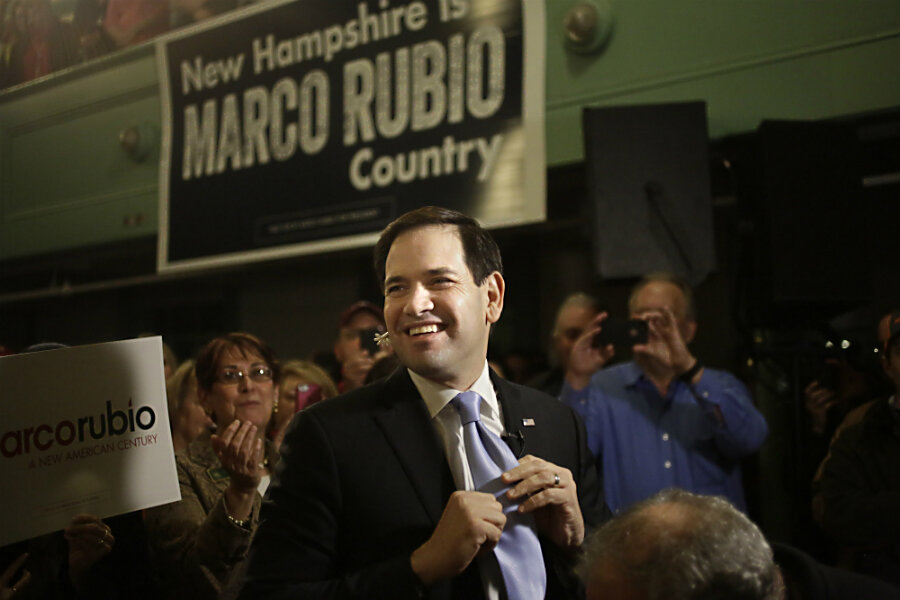

How Marco Rubio is putting the GOP back together again

Loading...

Six years ago, Marco Rubio was an outsider on the move, a tea party favorite who defeated an incumbent Republican governor to win a Florida Senate seat. Today he’s emerging as an insider favorite, the GOP establishment’s best hope to capture the party’s presidential nomination.

How he managed that transition and continues to balance between various Republican factions says a lot about how the party’s ideology has changed in recent years, as well as what constitutes an “establishment” in modern American politics.

The first thing to remember is that Senator Rubio is not now, and never has been, a moderate by the standards of what used to be called the GOP leadership. The man he beat in 2010, then-Gov. Charlie Crist, better fits that description. Mr. Crist ran as an independent after losing to Rubio in the GOP Senate primary. In 2012, Crist switched party allegiance and endorsed President Obama for reelection.

In contrast, Rubio’s record has been deeply conservative down the line. Almost. (The “almost” here is key, as we’ll see later.) As a US senator, he’s one of the most right-leaning members of Congress, notes the data journalism site FiveThirtyEight. As measured by DW-Nominate, an algorithm that rates lawmakers and their votes on an ideological spectrum, Rubio is more conservative than 77 percent of Republicans currently serving in Congress.

Given this, some on the right worry that Rubio is being redefined as a Republican centrist when he is not. Conservative talk host Rush Limbaugh said on Tuesday, “I don’t like this idea that all of a sudden, Marco Rubio is being labeled as an establishment candidate.... I don’t see Marco Rubio as anything other than a legitimate, full-throated conservative.”

Rubio’s reputation as a less-ideological political warrior stems in part from his years in Florida’s House. He rose to the state’s speakership and proved an adept dealmaker willing to delegate power to lower-ranking members.

In part, perceptions of Rubio as moderate stem from the fact that he’s running against more-conservative opponents. Sen. Ted Cruz is the most conservative member of Congress, according to DW-Nominate. The Texan anchors the right flank by himself.

But Rubio’s rhetoric and style are perhaps the biggest reasons pundits have lumped Rubio in with Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and other establishment candidates. He doesn’t portray Washington as a nest of locusts chewing up American greatness. He is soft-spoken and can be uplifting about the nation’s promise in general. He styles himself as a uniter.

“I live in an exceptional country where even the son of a bartender and a maid can have the same dreams and the same future as those who come from power and privilege,” Rubio said in his speech announcing his candidacy last April.

Enter “amnesty.” Perhaps Rubio felt his Senate participation with an immigration bill that contained a path to citizenship for undocumented workers would win establishment backing for his presidential bid. Instead, it’s become a scarlet “A” that’s marked him as a norm-breaker in the GOP primaries.

On immigration, Rubio’s party lurched right around him. Donald Trump has all but ensured that immigration will be a litmus test for all the Republican hopefuls. Now they’re competing to see who can sound the toughest on undocumented immigrants and noncitizen Muslims who may want to enter the United States.

In that sense, Trumpism may be winning, even if Mr. Trump himself lost the Iowa caucuses.

Rubio’s response has been to explicitly link immigration, illegal and otherwise, to national security. This has allowed him to maintain a bit of wiggle room on the status of current undocumented immigrants (“We are not going to round up and deport 12 million people,” he said in a recent GOP debate) while also sounding as tough as his rivals.

In some ways, Rubio is trumping Trump. He’s called for the legal immigration system to be “reexamined for security” in light of recent terrorist attacks. He’s praised Trump for “tapping into some of that anger that’s out there” with a call to ban entry of noncitizen Muslims. Asked at a recent debate about Trump’s call to close mosques, Rubio went a bit further, saying, “It’s not about closing down mosques. It’s about closing down any place – whether it’s a cafe, a diner, an Internet site – any place where radicals are being inspired.”

Other establishment candidates clearly see Rubio as their biggest threat. That’s why Mr. Bush’s super PAC has spent millions on ads mocking Rubio for wearing Florsheim boots and allegedly flip-flopping on issues. That’s why Governor Christie tore into Rubio in an unusually personal manner following the Iowa caucuses, calling the Floridian a “boy in the bubble” and questioning his toughness.

Rubio’s response made it clear that winning the backing of the establishment per se – the elected officials, consultants, donors, and so forth who make up the traditional party elite – is not his only concern. He attacked Christie’s “liberal record” on Common Core education standards, guns, and abortion.

“Marco is the only candidate who can unite conservatives and beat Hillary Clinton,” said Rubio campaign spokesman Joe Pounder.

Rubio’s Republican Party appears to be one where the ideological differences between factions are small. They are all conservative. Branding Christie as “liberal” is to try to cast him into the darkness beyond the campfire’s glow.

Party differences are about style and expressed anger, and Rubio is trying to adapt to that, while maintaining ties to an old guard that views Trump and Senator Cruz with disdain. Are conservatives, and thus the GOP, unitable at all? Rubio’s future hinges on the answer to that question.