Romney foreign policy: How different from Obama's?

Loading...

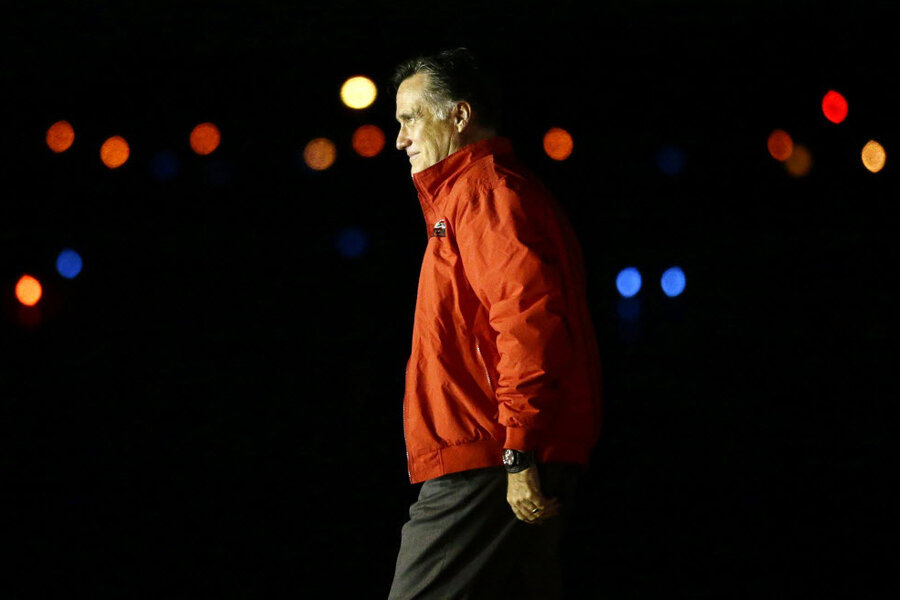

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney harshly criticized President Obama’s foreign-policy leadership in a speech Monday at the Virginia Military Institute.

Focusing on the Middle East, Mr. Romney accused the Obama administration of concealing for days the fact that terrorists were behind the attack in Benghazi, Libya, which killed US Ambassador Christopher Stevens and three other Americans. Also, Mr. Obama has put “daylight” between the United States and Israel, Romney said, and failed to halt Iran’s march toward nuclear weapons capability.

Under Obama, the US has “led from behind,” Romney said. Citing the example of VMI grad George Marshall, the great World War II Army chief of staff and Truman-era secretary of State, Romney vowed that as president he would use US power to shape world events, instead of simply reacting to them.

“Unfortunately, this president’s policies have not been equal to our best examples of world leadership,” Romney said.

Romney supporters saw the speech as building on the success of his crisp performance in the presidential debate last week. He “looked the part of commander in chief,” wrote conservative Jennifer Rubin in her Right Turn blog at The Washington Post.

This is one of the political hurdles that a candidate must overcome to topple an incumbent chief executive, of course. If voters are leery about a candidate's ability to handle late-night phone calls on foreign crises, they may hesitate to displace a tested administration.

Romney tried to do this with a light hand. There were no accusations that Obama had “sympathized” with rioters in the Middle East – a charge the GOP nominee has made in the past.

Instead, his tone seemed to reflect a core strategy of the Romney approach: Voters who still like Obama must be persuaded that it’s still OK to vote against him.

Romney “replaced righteous anger with sober disappointment and sought to give persuadable voters permission to feel the same way about the president’s foreign policy failures,” wrote BuzzFeed political writer McKay Coppins.

But some critics said that the foreign-policy themes that Romney enunciated relied heavily on repeated yet vague assertions that he’ll be a better leader than Obama. Also, they said, his actual policies hew fairly closely to existing US positions.

As to US relations with Israel, it does seem clear that a Romney administration would take a different tack, in that Romney vows to align the US more closely with Israeli interests. “The world must never see any daylight between our two nations,” he said.

On Syria, however, Romney said he’d work with allies to make sure rebels who “share our values” get the arms they need. That’s pretty much what’s going on now, though Romney might urge the transfer of more powerful weapons.

In Afghanistan, Romney hinted that Obama had pulled out troops too fast, but added, ”I will pursue a real and successful transition to Afghan security forces by the end of 2014.”

That’s the current Afghanistan timetable.

As for Iran, Romney has said that it should not get nuclear weapons capability. The Obama administration has been vaguer about exactly what line Iran should not cross. But Romney did not rattle sabers here, saying only that he’d impose new sanctions on Iran and tighten ones already in place.

Those are the tools the current administration says it will rely on for the time being to try to curb Tehran.

Both Obama and Romney have the same foreign-policy goals, writes Daniel Drezner, a blogger for Foreign Policy magazine. They want a peaceful, stable Middle East, for example. That’s unsurprising.

It’s in the means where they should differ. “And – in op-ed after op-ed, in speech after speech – Romney either elides the means altogether, mentions means that the Obama administration is already using, or just says the word ‘resolve’ a lot,” Mr. Drezner writes. “That’s insufficient.”

In fact, Romney has changed positions on a number of foreign issues, Madeleine Albright, Clinton-era secretary of State, said in a conference call with reporters. He’s switched back and forth as to whether the US intervention in Libya is a good thing, for instance.

“When you get to the specifics, you kind of don’t get the sense that he knows exactly what tools to use and how to operate within an international setting and what the role of the United States is in the 21st century,” said Ms. Albright.