Is cheap oil behind Obama's promise to veto Keystone XL bill?

Loading...

| Washington

President Obama offered a dubious welcome to the new Republican Congress Tuesday: a veto threat for their top priority, a bill approving the long-delayed Keystone XL pipeline.

Mr. Obama issued the veto threat in part to prevent congressional interference in the administration’s ongoing review, since the State Department has ultimate authority over Keystone XL. For years, Obama has put off making a decision, and the GOP hoped a new Congress would be the right time for a bill pushing Keystone XL. Now that Republicans control both chambers, a pipeline bill has enough support to make it to the president’s desk.

But it may also be the perfect moment for Obama to put his foot down and reject the controversial project. Domestic oil production is surging, lessening the demand for the Canadian oil Keystone XL would carry. Oil prices have also plummeted 50 percent in the past six months, and gasoline prices have fallen below $2 a gallon in a handful of states. That means Obama is less worried that blocking an energy project will rankle Americans.

“You don’t have the public on Obama’s back,” says Deborah Gordon, director of the energy and climate program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “There’s no one clamoring to get more oil out there, to bring the prices down. I think that probably is part of the president’s thinking here.”

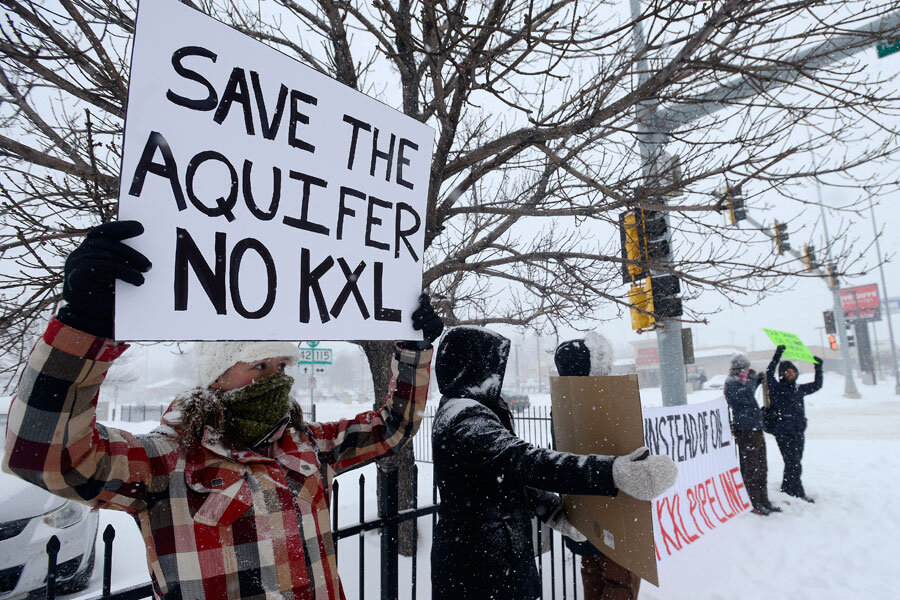

Keystone XL would carry 830,000 barrels a day of Alberta oil sands – and North Dakota and Montana crude – from the Canadian border to Texas Gulf Coast refineries. But the pipeline has become tied up in debates over climate change. Environmentalists blast the project, arguing that it would encourage development of Canada's emissions-intensive oil sands, or tar sands.

The fact that gasoline prices are low and that Keystone XL would encourage emissions-heavy oil sands "make it easier for Obama to say 'no,' " writes David Keith, a professor in climate science and public policy at Harvard University, in an e-mail to the Monitor.

Obama has said he will not give the green light if Keystone XL increases emissions and exacerbates climate change.

“There’s really no way to credibly argue that Keystone wouldn’t allow the substantial growth of tar sands production,” says Anthony Swift, a staff attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. “That in itself suggests very dim prospect for Keystone XL.”

The White House, in justifying the veto threat, pointed out that there are many administrative and legal hurdles the project needs to clear.

“The pipeline route has not even been finalized yet,” White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest told reporters Tuesday, referring to a Nebraska court case holding up the project.

Republicans probably don't have enough votes to override a veto, but the oil industry is confident that Keystone XL will eventually come to fruition.

Whether or not the pipeline is constructed should be strictly up to the Keystone’s builders, TransCanda, said Jack Gerard, president of the American Petroleum Institute, an industry group, at an API-hosted State of American Energy event Tuesday.

And industry is hopeful there are ways around Obama – by attaching approval to a must-pass bill, or by forcing Obama’s hand in some other way.

“There’s a lot of ways to get something done in this town,” Mr. Gerard said, adding that he’s encouraged by Congress’s growing frustration over Obama’s Keystone inaction. “I believe there’s growing support, even in the Senate.”

Sixty co-sponsors signed onto Tuesday’s Senate Keystone bill, and 60 is the number of votes needed to overcome a filibuster in the Senate. The Senate will debate the bill for “several weeks,” pro-Keystone Sen. John Hoeven (R) of North Dakota told reporters at a press conference Tuesday.

Some environmentalists think the latest veto threat is a sign Obama is inching toward an outright rejection of the project, but there’s still a chance Obama gives Keystone XL the go-ahead.

There are several reasons Obama would veto the current bill, even if he ultimately approves the pipeline.

“This is a decision, legally, which is up to the president. This is not a decision which requires congressional action,” says Robert Stavins, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

And that means even if Obama wants to approve the pipeline, he has little to gain by doing so now, when it would look like he’s capitulating to Republicans.

“It would make more sense for him to go forward with it later and get the credit for it, since either way he’ll get the ire of opponents of Keystone XL,” Professor Stavins says.