Senators reach jobless benefits deal: why bipartisanship is in bloom

Loading...

| Washington

It’s spring for bipartisanship in the Senate with several bright green shoots pushing through the surface this week.

These developments may not promise full-blown comity in the Capitol. But they are a welcome sign that lawmakers from both parties are finding ways to get things done – if not on big issues such as entitlements, the debt, and taxes, then at least on smaller ones.

- A bipartisan deal struck by five senators from each side of the aisle Thursday may solve the sticky problem of jobless benefits that expired on Dec. 28.

- The Senate overwhelmingly passed a bill Thursday to strengthen federally subsidized child care for low-income families. The Child Care and Development Block Grant Act, which serves 1.6 million children through funding to states, hadn’t been reauthorized since 1996.

- The Senate easily passed a House bill Thursday that rolled back skyrocketing flood insurance premiums affecting hundreds of thousands of homeowners, sending it to the president for signing.

- The Democratic chairman and top Republican member of the Senate Banking Committee on Tuesday announced a deal to replace Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – the two mortgage-finance giants that were taken over by the government in 2008 as the financial sector imploded. If it is approved by the full committee, it will be a significant piece of new legislation.

The motivation for each of the moves differs, meaning they say different things about the prospects for further bipartisanship going forward.

Election years can be powerful motivators for certain types of legislation. Clearly, the flood insurance bill is an attempt by Congress to assuage wrath at the ballot box. Huge premium hikes have stoked voter outrage in affected states, including Louisiana, where Sen. Mary Landrieu is up for reelection. She was a driving force behind the bill.

Similarly, the unemployment insurance deal plays off election-year themes. The compromise would retroactively restore five months of long-term jobless benefits, Politico reports, and be paid for by extending US customs fees and adjusting federal pensions. Now, Democrats may well be able to tout an accomplishment while Republicans have defused a potentially explosive issue.

"You combine the fact that polls for Congress are so atrocious, that public distrust is at historic lows, combined with midterm elections coming up and politically, a lot of legislators want to show that they can do something," says Julian Zelizer, a congressional historian at Princeton University in New Jersey.

The Freddie-and-Fannie agreement struck by the Banking Committee leaders touches on a more fundamental issue unresolved since the 2008 housing market collapse. It would replace the two enormous mortgage backers (they guarantee loans that account for more than half of a $10 trillion market) with a single new agency that provides less government support.

But a handshake is still a long way from a law, and, as congressional expert Ross Baker at Rutgers University points out, committees are not usually the problem. “The problem is when it gets to the floor.”

That’s when, as Republicans will bitterly tell you, Senate majority leader Harry Reid (D) of Nevada usually allows no Republican amendments. And that’s when, as Democrats will just as bitterly retort, Republicans often block votes or offer up politically loaded amendments.

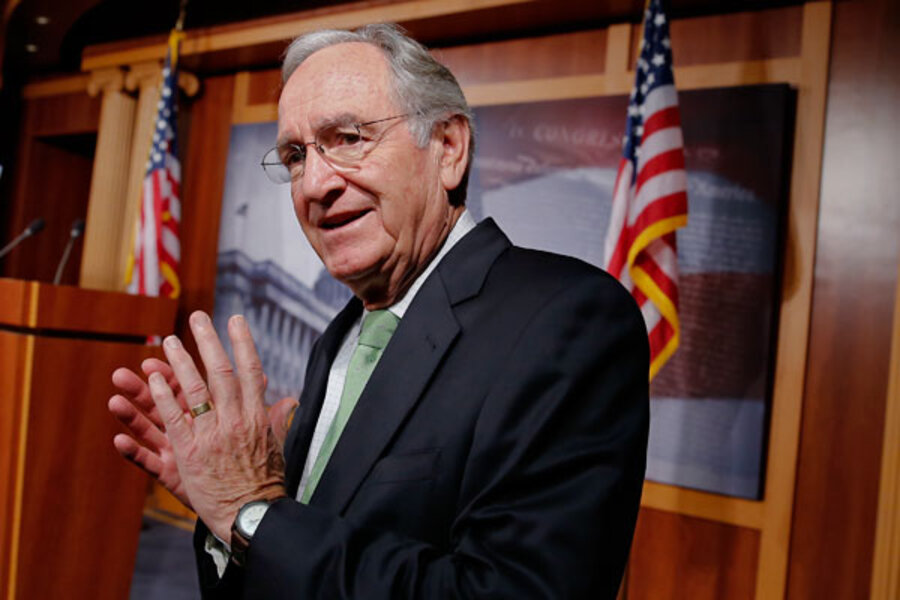

That explains why Thursday’s vote on the child-care act is noteworthy, if modest. Sen. Tom Harkin (D) of Iowa and Lamar Alexander (R) of Tennessee – the chairman and top Republican on the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee – ensured the bill went to the floor with the opportunity for amendments from both parties.

Senator Harkin approached Senator Reid and Senator Alexander went to minority leader Mitch McConnell (R) of Kentucky. Their deal: “We had an agreement,” Harkin said. “If spurious amendments are offered we’ll move to [block them]. If they’re on my side, he joins with me. If it’s on their side, I join with him.”

In the end, more than a dozen amendments from Democrats and Republicans were cordially discussed – and passed.

“We hope this is a good example of how the Senate can and should work,” Alexander said earlier in the week.

That example is important. Half the Senate has been there only since 2006, and for an institution that historically values tradition, those lessons need to be passed along. Many of the new senators have never seen the Senate function properly – what senators call “regular order,” notes Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D) of Maryland. To them, she says, regular order was chaos, confrontation, and blocking legislation or nominations.

“We want to change the tone so we can change the tide, and show that we can govern,” said Senator Mikulski, about the child-care bill that she co-sponsored with Sen. Richard Burr (R) of North Carolina. The bill passed 97 to 1.

Changing the tone is not so easy, considering the charged atmosphere in the Senate – particularly since Reid invoked the “nuclear option” in November, getting rid of the 60-vote threshold needed for confirmation of many presidential nominees.

But Mikulski, who has been in the Senate since 1987, seems determined to teach the newcomers how things used to be before all the senior senators retire. She and Senator Burr worked on the child-care act for three years and held more than 100 meetings with stakeholders, trying to find the balance between quality child care with the need to avoid excessive regulation.

“You know, it’s not magic to do the job,” she said. “The secret sauce is actually starting with mutual respect, identifying mutual needs, and trying to find that sensible center using courtesy and civility.”