Senate simmers down after two all-nighters, but what was the point?

Loading...

| Washington

Last week, as negotiators shook hands over a bipartisan budget deal that passed by a wide margin in the House, Republicans and Democrats in the Senate all but threw punches.

Senate Republicans were in full retaliation mode for the recent “power grab” by Democrats that limited the use of the filibuster to block presidential nominations.

When Democrats invoked the new rule to sweep aside GOP opposition and allow confirmation of nominees by a simple majority, Republicans used other rules to slow the process to a crawl.

Democrats hit back by scheduling votes at odd hours of the day and night.

Minor kerfuffle? Or skirmish of consequence?

The Senate pulled two all-nighters; tired junior senators had to preside over an empty chamber in the wee hours; stenographers worked in shifts; raw accusations were traded during long debates.

And then it was over.

On Friday, the Senate’s leaders agreed to end the round-the-clock sessions and take up two nominations at a normal hour Monday, then move on to the House budget agreement and the defense bill – though another set of nominations later in the week could again spark drawn-out debate, including over Janet Yellen to head the Federal Reserve.

Friday’s cease-fire begs the question: What was the point of this exercise?

The issue at hand – changing the rules on the filibuster on most presidential nominees – is not inconsequential, even if a bit inside baseball.

The filibuster has long contributed to the distinct identity of the Senate as a deliberative body, the so-called cooling “saucer” to the hot-headed House. It has a pause-and-reconsider function, giving any senator the right to delay action on a bill or nominee indefinitely, or until 60 votes can be found to stop the delay.

But it also has a blocking function. Back in 1975, senators briefly got rid of it altogether. The uproar, however, was so great, that the effort failed. Instead, a deal was brokered to reform the filibuster: requiring only 60 votes, instead of 67, to overcome it.

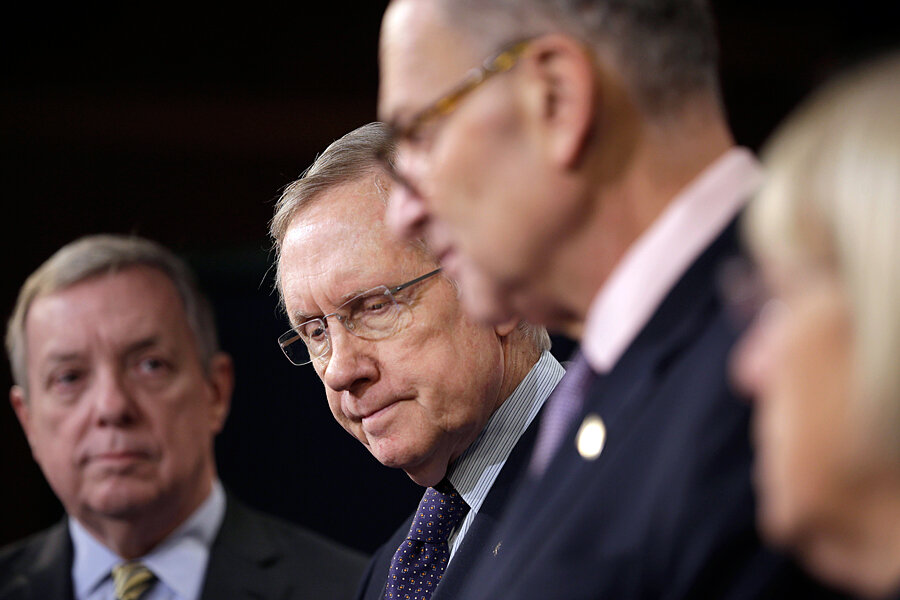

When Republicans threw sand in the gears last week, a similar revolt seemed underway. Were they pulling a 1975, hoping that the Senate majority leader, Harry Reid (D) of Nevada, might back down? Before the Thanksgiving recess, he had invoked “the nuclear option” to do away with the filibuster for most presidential nominees – though not for the Supreme Court, nor for legislation.

But Republican Sen. Bob Corker (R) of Tennessee says there’s no expectation that the majority leader will reverse course. The GOP strategy is simply to push back. “If there’s not some degree of pushback,” he says, Democrats “will continue to take short cuts” rather than “go through the effort of actually leading.”

It’s not clear whether the Republicans will resume retaliation-through-delay either later this week, when more nominations are expected to come up, or in the new year.

Unless pushing back actually causes Mr. Reid to change his mind (unlikely) or so delays action that Americans start to take notice, the fight over the filibuster will continue to be one that mostly has the attention of the senators themselves.