President Nixon took the Kennedy-era IRS political strike force and redirected it to target left-wing groups. But Nixon appears to have targeted a wider range of "enemy" groups for tax audits, including antiwar groups (and the churches and other nonprofits that sheltered them), civil rights groups, reporters, and prominent Democrats.

Moreover, as a result of Watergate investigation (1973-4) and, especially, the disclosure of White House tapes, many of these activities became public. The tapes provided a direct line of accountability from the IRS to the Oval Office that was often missing in previous administrations.

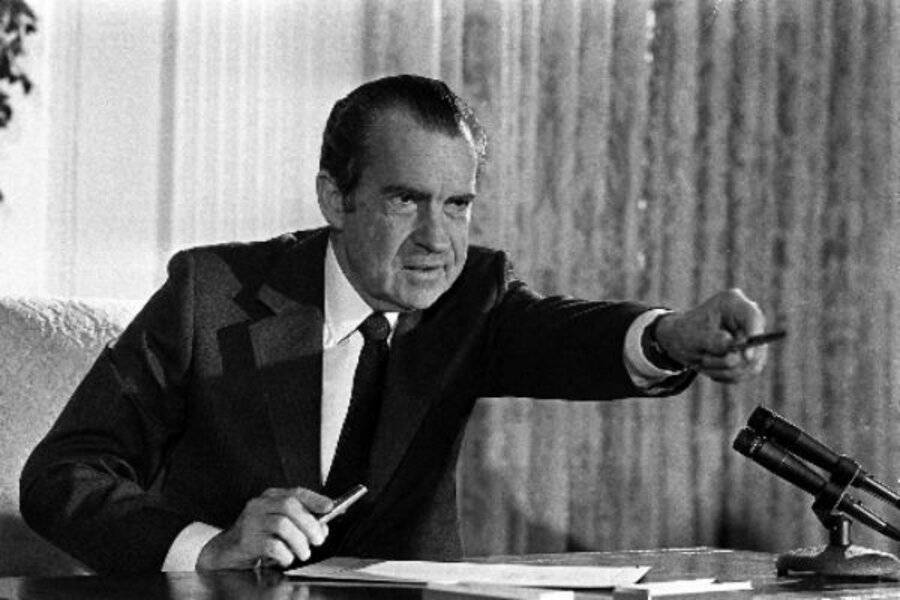

Nixon is unambiguous: He directs aides to use the IRS to get back at political enemies. In a taped conversation on Sept. 8, 1971, Nixon tells his chief domestic policy adviser, John Ehrlichman, to direct the IRS to audit potential Democratic rivals, including Sens. Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, and Edmund Muskie of Maine.

"Are we going after their tax returns? I ... you know what I mean? There's a lot of gold in them thar hills," Nixon said.

The House Judiciary Committee noted Nixon's abuse of the IRS in its Articles of Impeachment, charging that Nixon "acting personally and through his subordinates and agents, endeavoured to obtain from the Internal Revenue Service, in violation of the constitutional rights of citizens, confidential information contained in income tax returns for purposes not authorized by law, and to cause, in violation of the constitutional rights of citizens, income tax audits or other income tax investigations to be initiated or conducted in a discriminatory manner."